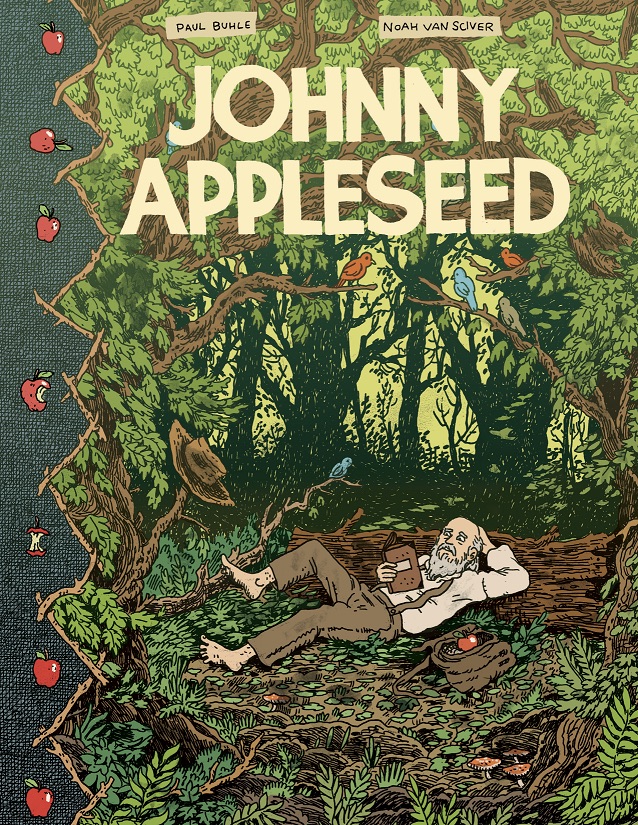

Paul Buhle and Noah Van Sciver’s graphic history tells a tale very relevant to our time.

[Johnny Appleseed: Green Spirit of the Frontier, a graphic history written by Paul Buhle and illustrated by Noah Van Sciver (September 5, 2017: Fantagraphics Books); Hardcover; 112 pp; $19.99.]

Before there was organic farming, there was… organic farming. Before Rachel Carson, Bill McKibbon, or Michael Pollan, there was… Johnny Appleseed.

Appleseed, as he is known in myth, was born John Chapman in Leominster, Massachusetts, on September 26, 1774, and of all the figures of the U.S. frontier, real or imagined, from Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone (real) to John Henry and Paul Bunyan (imagined), he is perhaps the most suited to our climate-imperiled times.

Chapman, whose death in 1845 might have gone unremarked by history, was raised to mythic status by a writer for Harper’s Monthly in the late 1800s, when readers’ fascination with the frontier seemed insatiable. Over the years he became the subject of so many stories that it took scholars of the 20th century years to untangle the few skeins of truth in his legend. Most of the myths ended up in brightly illustrated children’s books, although there are several scholarly adult works.

The book places Chapman in the socio-political-religious context of his time.

And now, historian Paul Buhle and graphic artist Noah Van Sciver have created a graphic biography of Chapman that places him in the socio-political-religious context of his time and shows his perhaps subliminal influence on the environmental movement of today.

(Full disclosure: I’ve met Buhle once or twice and contributed to The Encyclopedia of the American Left edited by him, Mari Jo Buhle, and Dan Georgakas. I also enjoyed his illustrated history of another mythic figure: Robin Hood: People’s Outlaw and Forest Hero: A Graphic Guide and have helped with fundraising for his and Van Sciver’s graphic biography of Eugene Debs, forthcoming from Verso.)

Let’s recap in case you missed the original version. Chapman appears in the late 1790s in Pennsylvania and the early 1800s in Ohio on what is still the frontier. A kindly cider mill owner gives him apple seeds that would have been thrown out, and Chapman plants them everywhere he goes, bringing nourishment and beauty to the lives of indigenous inhabitants, whose orchards had been destroyed, and to the white settlers pushing ever westward.

He tends to a wounded wolf who

then follows him like a pet.

Along the way, he asks nothing but a floor to sleep on, some food, and cast-off clothing, some of which is made from old feed bags. Birds and animals love him, as do children. He tends to a wounded wolf who then follows him like a pet. He sleeps in a hollow log at the other end of which are a mother bear and cub and lives to tell the tale. He is known for literally not hurting a fly.

The part I don’t remember from childhood telling is that he is also a missionary of the Swedenborgian religion, a mystical sect based on the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg, whose adherents often communed with angels and members of the spirit world. But, of course, I do remember the grace we sang at Girl Scout Camp and in Sunday School that is attributed to him and that some historians believe is based on a Swedenborgian hymn. Buhle credits its popularity to a short segment in the 1948 Disney film Melody Time.

Chapman personified the Swedenborgian belief in eschewing earthly goods as well as the equally radical one of inclusivity and equality of all humans. In a time when every white male on the frontier who could afford it carried a rifle or gun, Chapman was a “non-resister,” i.e., pacifist, and a vegetarian. Where others saw the indigenous population as subhuman impediments to westward expansion, he saw them as fellow beings with whom he had much in common and who had much to teach him.

His apples were fit only for

cider and vinegar.

When others looked to more and more modern methods of agriculture, Chapman resisted the opportunity to graft apples and create juicy, good-looking produce. His apples were fit only for cider and vinegar, causing Michael Pollan to call him the “American Dionysius.” Alcohol brought solace on the lonely and harsh frontier, and apple cider vinegar was a staple home remedy that persists today in homely glass bottles or in fancy brown mini-jugs of high-end “fire cider” found in health-food stores and brewery boutiques.

Although he might have needed only “the sun, the rain, and the apple seed,” Chapman understood some basic economics. Land was a precious commodity, and land speculators were buying up huge tracts, but state governments would give or lease land at low cost to anyone who would clear it, plant it, and build on it.

Having apprenticed with a nurseryman in Massachusetts, Chapman understood what was necessary for a low maintenance apple orchard. He would lay claim to the land, clear it, plant trees, move on, return in a few years and sell the young trees to newly arrived settlers (very often on credit or at a low price), replenish his supplies, and light out again for the ever-expanding frontier.

Buhle places Chapman on the cusp of religious revivals and socialist thought.

Buhle takes some side trips to tell us about the symbolic importance of apples in religious myth (think Pomona, Roman goddess of orchards, or Adam and Eve and the Tree of Knowledge) and, more important, places Chapman on the cusp of religious revivals, socialist thought (utopian socialist Robert Owen was also influenced by Emanuel Swedenborg’s writings), the burgeoning spiritualism that rose along with the industrial revolution, and the abolitionist movement.

Chapman died in 1845, but Buhle links him ideologically and spiritually to others influenced by Swedenborg, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Victoria Woodhull (the first to publish “The Communist Manifesto” in this country), along with many others. Through his wanderings and love of nature, Buhle links him to the fictional Tom Joad and real Woody Guthrie; naturalist John Muir; Buddhist poet Gary Snyder, who worked as a fire warden in a national park; and the growing environmentalist movement.

Little is actually known about Chapman except that he lived a life that inspired others even if they could not always emulate his self-sacrifice and good will. In a part of the book tacked on to the end, Buhle takes us to Italy, where we see a young Francis of Assisi, who speaks to the birds and animals and preaches a gospel of poverty and service, then to the Vatican, where we see the current pope, who has taken the name of Francis and who preaches the care of creation. Robin Hood and King Arthur make brief appearances to remind us of the liberatory power of myth. Like the grafts that Chapman disdained, these sections make good food for thought but don’t quite belong to the main tree.

In 112 packed, illustrated pages, Buhle and Van Sciver cover a lot that you probably didn’t learn in U.S. history class. Like the cider made from Johnny’s apples, it goes down well.

[Maxine Phillips is a co-convener of the Religion and Socialism Working Group of Democratic Socialists of America, is co-editor at religioussocialism.org, and is co-writer of an elementary and middle school curriculum using children’s literature to teach conflict resolution.]

- Read articles by Maxine Phillips on The Rag Blog.

- Find articles by and about Paul Buhle on The Rag Blog.

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s two Rag Radio interviews with Paul Buhle.