The story may be set in Finland, but the

plot is universal.

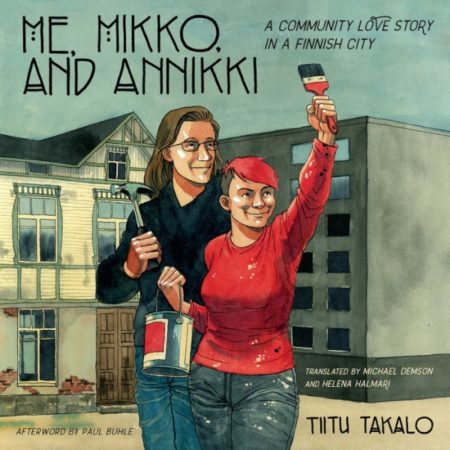

[Me, Mikko, and Annikki, A Community Love Story in a Finnish City, by Tiitu Takalo, translated by Michael Demson and Helena Halmari, afterword by Paul Buhle, North Atlantic Books, 2019]

A young woman and man lift hammer and paintbrush in (perhaps) unconscious homage to Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” or some propaganda poster of socialist realism as they stand in front of their recently renovated home. Behind those triumphant gestures lies the long, intricate love story of the title.

This nonfiction comic from Finland promises two love stories: one personal, one political, and both entwined. The first is between the “Me” and Mikko of the title. The author, a well-known feminist artist, falls for Mikko, an engineering student (horrors!!) who pursues her with a wry doggedness. The second is between the two of them and Annikki, a housing co-op whose history Takalo traces through the Middle Ages, industrialization, and up to the present day.

The story may be set in Finland, but the plot is universal. Tiitu and Mikko dream of a home larger than the box they live in, and after years of community action and sweat equity by all concerned, they move into their dream apartment. Along the way, as anyone knows who has rehabbed a building, they will either break their bonds or forge stronger ones.

We discover the roots of a cooperative culture that still has echoes in the U.S.

And along the way we, the readers, learn more about Finnish history and the development of Tampere, the city in which Annikki is located, than we thought we wanted to know. We discover the roots of a cooperative culture that still has echoes in the United States and can identify with community activists who fight against the power of developers, real estate interests, and city hall.

Co-translator Michael Demson describes how he read about the book, searched for an English translation, couldn’t find one, and determined to bring this work to an English-speaking audience. Demson, author of Masks of Anarchy, the Story of a Radical Poem, from Percy Shelley to the Triangle Factory Fire, illustrated by Summer McClinton, found a helpful colleague, Helena Halmari, editor of the Journal of Finnish Studies. They soon enlisted another enthusiastic reader, Paul Buhle, whose Afterword highlights not only the art work but Annikki’s place in radical history. [Full disclosure: I serve on the board of the Democratic Socialists of America Fund, which helped bring Buhle’s co-authored graphic bio of Eugene Debs, illustrated by Noah Van Sciver, to press.]

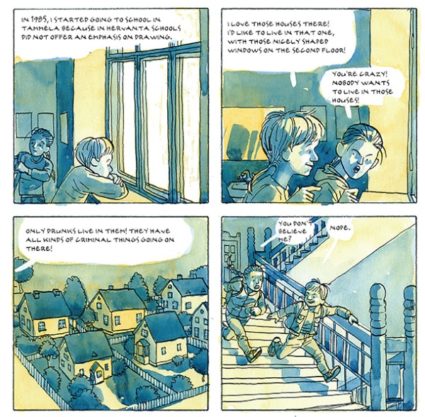

So, who else will love this book? Well, there’s anyone who appreciates comic art. Every panel invites a second and then a third look. Each section has its own story and character — from the earthy browns and woodcut-style figures of the Middle Ages to the vibrant dancers at a rock concert who fairly leap off the page. They are different communities, living in different times, and we learn of their dreams and struggles. With humor and skill, Takalo takes us through the history of the working-class residents as Tampere grows from market town to industrial center, the “Manchester” of Finland. There are allusions to its left-wing history and to the lingering pall of the violence of the civil war and slaughter of the Red Guards in Tampere. Today, the town is home to high-tech industries and has a vibrant music and art scene. The Annikki poetry festival draws large crowds every two years. Think San Francisco or Brooklyn.

Developers have moved in to tear down old stock and build high-rises.

And like those other cities where the industrial base has disappeared, housing prices have skyrocketed. Developers have moved in to tear down old stock and build high-rises. Annikki, as Buhle points out, is the last section of town to have buildings that date from 1910 and “has every right to be preserved for that reason alone.” But what the book tells is a story of people who organize both to save a neighborhood from “development” and then to create in it a co-op in the grand tradition of Finnish co-ops, which extends far beyond housing. In scenes familiar to any activist in this country, we see the town meetings, the canvassing for petition signers, the disappointment as effort after effort stalls and it seems as if the developers and their friends in high places will win. And we see the determination of people who will not give up. Ever.

The story doesn’t end when the people win the right to rehab the buildings. There are the meetings, the endless meetings. Would-be residents debate everything from colors for common spaces to what kinds of fixtures to install and which contractors to hire. Takalo screams at Mikko when he orders black light switches for their new home. She wanted white. She gets a grip and does some self-talk to stop sweating the small stuff. There’s more than enough large stuff, as the inhabitants — who work on clean up, plastering, and painting in the evenings after they leave their day jobs — come close to dropping from fatigue. Like the effort to create and maintain community, or nurture a relationship, for that matter, the story never ends.

Finns brought their co-operative ethos to the shores of the United States, creating the first housing co-ops in New York City and inspiring other socialists in unions to build co-ops for workers. When we read radical history and labor history, we can only imagine the struggles of our forebears. By showing, rather than telling, Takalo inspires us to create our own community love stories.

[Maxine Phillips is the volunteer editor of Democratic Left and former executive editor of Dissent magazine.]