U.S. Medical Personnel and Interrogations: What Do We Know? What Don’t We Know?

By Sheri Fink / April 9, 2009

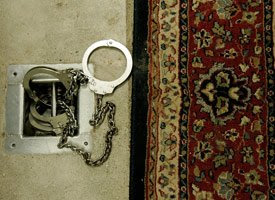

This week’s posting of a confidential International Committee of the Red Cross report (PDF) about the treatment of 14 “high value detainees” held in secret CIA prisons has again raised a nettlesome question: In exactly what ways were medical personnel involved in abusive detainee interrogations?

The report, put online by The New York Review of Books in connection with articles written by Mark Danner, was based on interviews with the detainees who had been kept isolated from each other. ICRC media delegate Bernard Barrett confirmed in an e-mail that the report was authentic. “We have publicly deplored that this confidential material was made public as that was never our intent.” (The ICRC provides this explanation of its role.)

The detainees reported that health personnel generally provided them with high-quality medical care, but also said that some health workers oversaw or participated in “ill-treatment” such as beatings and waterboarding.

One detainee alleged that a health worker told him, “I look after your body only because we need you for information.”

Responding to questions from the New York Times, CIA spokesman Mark Mansfield said his agency had long ago ended the interrogation program and the agency, as directed by the Obama administration, will only use techniques that fall within the Army Field Manual (PDF).

To put the new information into perspective, ProPublica offers these answers to key questions about the roles of American medical personnel in detainee treatment in recent years.

What is known about the involvement of health professionals in the interrogations?

For years, reporters have been detailing the roles of psychologists and psychiatrists in the now-abandoned interrogation practices.

“Psychologists, working in secrecy…actually designed the tactics and trained interrogators in them while on contract to the C.I.A.,” Katherine Eban wrote for Vanity Fair in 2007.

Psychologists James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen reportedly “reverse-engineered” tactics from a military training program known as SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape), originally designed to help captured U.S. soldiers withstand abusive treatment. They then showed military and CIA interrogators how to apply the tactics to detainees in an effort to break them down, according to articles and Jane Mayer’s book “The Dark Side.”

The two have not discussed their role with journalists, but they did release a statement in response to the Vanity Fair article stressing their opposition to torture. They said they were proud of their work for the country and that their actions and advice were legal and ethical. “Under no circumstances have we ever endorsed, nor would we endorse, the use of interrogation methods designed to do physical or psychological harm.” We also called Mitchell Jessen and Associates consulting firm for comment and were told, “It is their policy not to give interviews.”

Psychologists and psychiatrists, sometimes working as Behavioral Science Consultation Teams (known as “BSCTs”), reportedly helped craft interrogation plans for specific detainees, a role they may still be playing in spite of opposition from professional medical associations, according to an Army medical policy document issued in 2006 and recently made public by the New England Journal of Medicine. The Army stressed that BSCT medical personnel were applying their knowledge to information-gathering and were not involved in providing medical care to the detainees, helping avoid a conflict in loyalties.

Criticisms have also been leveled at the access military and CIA interrogators had to detainees’ medical records and their ability to direct health personnel to provide them with information (PDF). After reviewing Defense Department interrogation operations in 2004, the military acknowledged (PDF) that in Iraq and Afghanistan, “interrogators sometimes had easy access to such information” but found that they did not use it inappropriately.

What other issues have been raised?

Early reports focused on abusive treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq. Col. Thomas M. Pappas, chief of military intelligence at Abu Ghraib, who was interviewed as part of the Taguba investigation, testified that a psychiatrist and another doctor monitored interrogations (PDF) at the prison and had the final say in what aspects of the interrogation plan were implemented.

Military doctors and nurses were criticized for failing to report evidence of abuse. In a few instances, detainees who were initially certified by physicians as having died of natural causes were later acknowledged by the Pentagon to have died of homicides due to asphyxia or blunt force injuries.

The health system for detainees at Abu Ghraib was found to be poorly equipped and understaffed. Geneva Conventions requirements to provide monthly health inspections and allow prisoners to request proper medical care were not fulfilled there and in Afghanistan, according to internal military investigations described in the Lancet in 2004 and in the book “Oath Betrayed” by ethicist Steven Miles.

After the scandal broke, the Department of Defense reviewed its procedures for medical personnel dealing with detainees and, in 2005, issued more specific guidelines that called for personnel to be guided by medical ethics and report inhumane treatment.

The Office of the Army Surgeon General also conducted an extensive assessment of detainee medical operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and Guantanamo beginning in late 2004. While it concluded that medical personnel had made extraordinary efforts to provide “compassionate and dedicated care” to prisoners and detainees, it also found problems with the security of medical records and the extent to which medical personnel were trained about the need to report suspected detainee abuse.

The report recommended that all medical personnel be prohibited “from active participation in interrogations” and that psychiatrists and other physicians no longer be part of BSCTs. Former Army Surgeon General Kevin Kiley did not approve the latter recommendation.

What do standards of medical ethics have to say about health professionals participating in detainee questioning?

When it comes to torture and other mistreatment (as opposed to lawful interrogations), widely accepted standards of medical ethics are clear: Physicians and other health personnel cannot participate, facilitate or be present. Physicians and other health professionals are also forbidden from using their specialized knowledge and skills to facilitate ill treatment.

When captives are brought to detention sites, they must be given medical checks and ongoing care, and doctors must report any suspected abuses up the chain of command. The role of health professionals “is explicitly to protect [detainees] from … ill-treatment,” according to the ICRC report. If a detainee has a medical emergency during questioning, a physician can be called in to provide treatment.

Recently, medical societies have laid out strict policies that restrict their members’ participation in even lawful interrogations. The American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics was updated in 2006 to ban physicians from conducting interrogations or monitoring them “with the intention of intervening in the process.” The reason for this is described in the ICRC report: “Any interrogation process that…requires a health professional to monitor the actual procedure, must have inherent health risks” and is thus “contrary to international law.”

The American Psychiatric Association issued an even broader ban on involvement in interrogations, forbidding psychiatrists from being in a room where an interrogation is ongoing.

The American Psychological Association took a different stance in 2005, opposing torture but expressly acknowledging a role for its psychologist members in gathering information that “can be used in our nation’s and other nations’ defense,” including serving as interrogation consultants. The task force that made that recommendation was later criticized as being biased. Last year, the association approved new guidelines that would restrict psychologists from participating in interrogations at sites that violate international law or the U.S. Constitution.

What questions remain?

The list of unknowns is long. How, why and when the CIA brought SERE-affiliated psychologists and psychiatrists into the interrogation strategy of detainees remains a mystery.

The question of how effective the practices they allegedly developed were at eliciting useful intelligence also remains a matter of debate, with recent media reports casting doubt on the usefulness of intelligence obtained from one of the captives, Abu Zubaida. Last month on CNN former Vice President Dick Cheney defended his administration’s programs dealing with suspected terrorists as “essential to the success” in preventing attacks on U.S. soil after 9/11.

The exact roles medical personnel are playing in presumably lawful interrogations being conducted today are also unclear.

Also unknown are the identities of most of the medical personnel involved in abusive interrogations. Their numbers may be small. The Office of the Army Surgeon General queried more than 1000 medical personnel from more than 180 military units (nearly 900 had served or were serving in Iraq, Afghanistan or Guantanamo) and found only five instances of medical personnel participating in interrogations.

Are there any investigations coming?

Sen. Patrick Leahy recently proposed a nonpartisan commission of inquiry to “get to the truth of what went on during the last several years.” In a statement last week, Leahy said that the ICRC report and other recent revelations demonstrate “why we cannot just turn the page without reading it.”

The advocacy organization Physicians for Human Rights is calling for the proposed commission to “document the use of the healing professions to design, supervise, and implement a regime of abuse.” The group wants health professionals who participated to be referred to state licensing boards, which could consider stripping them of the right to practice.

An aide to Leahy told ProPublica that an exploration of medical professionals’ roles “remains to be determined…There’s no bill or detailed proposal.” The senator’s statement expressed his concern not to “scapegoat or punish those of lesser rank.”

Source / Pro Publica