‘Greatest surgeon of the 20th century’ dies

By Todd Ackerman and Eric Berger

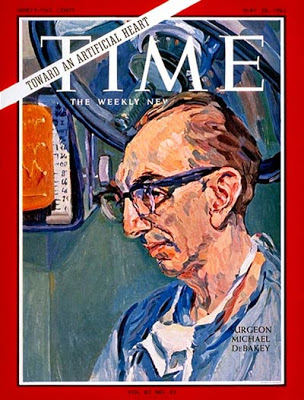

Dr. Michael Ellis DeBakey, internationally acclaimed as the father of modern cardiovascular surgery — and considered by many to be the greatest surgeon ever — died Friday night at The Methodist Hospital in Houston. He was 99.

Medical statesman, chancellor emeritus of Baylor College of Medicine, and a surgeon at The Methodist Hospital since 1949, DeBakey trained thousands of surgeons over several generations, achieving legendary status decades before his death. During his career, he estimated he had performed more than 60,000 operations. His patients included the famous — Russian President Boris Yeltsin and movie actress Marlene Dietrich among them — and the uncelebrated.

“He was a great contributor to medicine and surgery, of course,” said Dr. Denton Cooley, president and surgeon-in-chief at the Texas Heart Institute in Houston and a longtime DeBakey rival.

“But he left a real legacy in the Texas Medical Center and at Baylor College of Medicine, where he’s brought so much attention. Together we were able to establish Houston as a world leader in cardiovascular medicine.”

Cooley had known DeBakey since 1945. “In the first half of the 20th century, very little went on in this field,” he said of cardiovascular surgery. “So when he and I began our careers, we pretty much had an open field.”

“Dr. DeBakey singlehandedly raised the standard of medical care, teaching and research around the world,” said Dr. George Noon, a cardiovascular surgeon and longtime partner of DeBakey’s. “He was the greatest surgeon of the 20th century, and physicians everywhere are indebted to him for his contributions to medicine.”

Debakey almost died in 2006, when he suffered an aortic aneurysm, a condition for which he pioneered the treatment. He is considered the oldest patient to have both undergone and survived surgery for it. He recovered well enough to go to Washington earlier this year to receive the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the nation’s two highest civilian honors.

“The full weight of his contributions may not be known for many years, but everyone who knew him gravitated to his kindness, warmth and spirit,” U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, R-Texas, said in a statement Saturday. “He was still innovating in medicine until his last breath.”

He remained vigorous and was a player in medicine well into his 90s, performing surgeries, traveling and publishing articles in scientific journals. His large hands were steady, his hearing sharp. His personal health regimen included taking the stairs at work and a single cup of coffee in the morning.

DeBakey’s death was mourned Friday night by the leaders of Methodist and Baylor. Methodist President Ron Girotto said, “He has improved the human condition and touched the lives of generations to come. We will greatly miss him.”

And Baylor President Dr. Peter Traber added that “he set a standard for preeminence in all areas of his life that those who knew him and worked with him are compelled to emulate. And he served as a very visible reminder of the importance of leadership and giving back to one’s community.”

Debakey was born in Lake Charles, La., in 1908, a month before Ford began making Model Ts and a quarter-century before the discovery of bacteria-fighting drugs. His genius helped shape surgery and health care as we know it. While still in medical school, he developed the roller pump for the heart-lung machine. DeBakey invented many of the procedures and devices — more than 50 surgical instruments — used to repair hearts and arteries today.

He is widely credited with laying the foundation for the Texas Medical Center in Houston by recruiting pre-eminent doctors and researchers and giving the city an international reputation for leading-edge health care. He was a maverick, running afoul of the Harris County Medical Society for insisting that surgeons be certified by the American Board of Surgery. At the time, it was common for general physicians to operate.

“DeBakey built a department of surgery at Baylor and at The Methodist Hospital, which was to become one of the most celebrated in the world, a galaxy of young stars,” the late author Thomas Thompson wrote in 1970 in Hearts: Of Surgeons and Transplants, Miracles and Disasters Along the Cardiac Frontier. “In a city where 25 years ago there was practiced medicine of the most mediocre sort, there sprung up in a swampy area six miles south of downtown … one of the handful of distinguished medical centers in the world.”

He invented and refined ways to repair weakened or clot-obstructed blood vessels using replacements made from preserved human blood vessels, and later, with artificial ones. He is credited with the first successful surgical treatment of potentially deadly aneurysms of various parts of the aorta. He co-authored one of the earliest papers linking smoking and lung cancer in 1939.

“Dr. DeBakey is a legendary figure in medicine and a mentor to hundreds of practicing doctors and medical students. The full weight of his contributions may not be known for many years, but everyone who knew him gravitated to his kindness, warmth and spirit,” U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, R-Texas, said in a statement.

During World War II, serving in the office of the U.S. Surgeon General, DeBakey’s work led to the development of mobile surgical hospitals, called MASH units. He helped President John F. Kennedy lobby for Medicare; he recommended creation of the National Library of Medicine, subsequently authorized by Congress. In 1963 DeBakey won the Lasker Award for Clinical Research, considered the U.S. equivalent of a Nobel.

“At times he could act like the meanest man in the world. He didn’t let you breathe,” said Dr. John L. Ochsner of New Orleans, who trained under DeBakey and whose father, Dr. Alton Ochsner, was DeBakey’s mentor at Tulane University School of Medicine. DeBakey baby-sat the four Ochsner children, including John, and let them do chin-ups on his arm.

Said John Ochsner, “The thing that made him so mad all the time was he was trying to conquer the world and every minute was so important to him. He didn’t have time for frivolity at all.”

Patients and their families saw him otherwise. To them, DeBakey was a healer with quiet authority who seemed to work miracles. Enfolding a patient’s hands in his, the patient’s face would relax, some recalled.

He was pained by the breakup in 2004 of the historic, 50-year marriage between Baylor and Methodist, which dissolved over disagreements about the future of the institutions. DeBakey said the breakup made no sense and hurt both parties. Friends described him as “heartbroken” about the split and in an interview earlier this year he said the description was not inaccurate.

In 2003, his MicroMed DeBakey LVAD was implanted in a 10-year-old girl, the youngest patient in the world to receive the device. In 2004, a special child-sized version became available for children as young as 5. DeBakey developed the device, which boosts the heart’s main pumping chamber, in collaboration with heart surgeon Noon and NASA.

“The man has an incredible mind and an incredible grasp of details,” said former MicroMed CEO Travis Baugh . “He’s also never stopped inventing. We are working on a project with him a new way of attaching sutures to the heart.'”

Real the rest of this article here. / The Houston Chronicle

The Rag Blog

RIP but where is the surgeon who can put heart into the administration of the body politic?