I picked up a copy of the Columbia Alumni bulletin off the floor of my education classroom at San Francisco State in the spring of 1868, and I could tell the University was putting up a snow job for the grads to diminish the significance of the strike.

I’m glad to see they cared enough about it to have a 40 year reunion! [April 24-27, 2008] It really was a different sort of student strike than most we had seen at this time, because it focused on the University and its encroachment on the surrounding community, in this case, a predominantly black community. The Berkeley commotion over People’s Park being built on by the university, displacing the local hippies and street people, pales in comparison (pun intended).

The following article is by Hilton Obenzinger, a friend of mine, a Stanford professor and long time peace activist who participated in the strike and occupation. The article raises a lot of parallel issues for our current political period. It says a great deal about the lack of understanding and agreement between black protesters and white student protesters in the strike.

Alice Embree’s piece [A. Embree : 1968 Columbia Student Revolt Remembered in New York, The Rag Blog, May 3, 2008] did a good job of looking at the conference itself, and its interaction with current community issues. I can imagine that it was a very lopsided affair in terms of gender participation, as was the original protest. Hilton discusses this in his article, pointing out the fact that Columbia itself was an all male college in those days. Barnard was much smaller and didn’t get quite so involved in the strike, although in terms of leading the charge, two Barnard women, including one whom Hilton and Alice both mention in their articles, hurled a battle cry that brought the argumentative males to their feet and out the door!

Jon Ford / The Rag Blog / June 2, 2008

Columbia Student Rebellion 1968 – 40 Years Later

by Hilton Obenzinger

Paul Spike was going to participate in “Voices of 1968,” a reading featuring poets, novelists and other writers as part of a conference commemorating the 1968 student occupation and strike at Columbia, and he wanted me to take a look at the piece he had just written. I sat with Paul just before the reading on the ledge in front of Columbia University’s famous Alma Mater statue on the steps of Low Library, our backs against the pedestal.

Alma Mater sits with a book on her lap and her arms outstretched to both sides, the mother of wisdom offering herself to all of her children. Anti-war students had pulled a black hood over her head and connected mock electrodes to her hands a couple of days before. The iconic statue had turned into yet another icon, the hooded crucifixion image of Abu Ghraib.

Paul writes novels and non-fiction – he’s also a journalist, the first Yank to edit Punch. For this event, he wrote of the murder in 1967 of his father, the Protestant minister who led the civil rights work of the National Council of Churches, marching with Martin Luther King in Selma and elsewhere. The murder remains unsolved. Paul has long suspected that the murder was a political assassination – but his grief was only an entry point to his main purpose: to offer an apology to Columbia’s black students of 1968.

Why an apology?

Forty years before, Columbia had wanted to build a gym in Morningside Park, and the community and students (and the parks commissioner and the mayor) objected to the landgrab by a private entity of a public park. And to make it even uglier, the magnanimous university allowed for the Harlem community to use a small part of the gym, except that the students (almost all white) would enter from the front door and, as the park sloped down hill toward Harlem, the black community would enter the facilities from the back door. This smacked of Jim Crow – in fact, we called it Gym Crow – and it was emblematic of the way the university lorded over Harlem. At the same time, the university persisted in conducting counter-insurgency research to support the Vietnam war, despite avowals by President Grayson Kirk and others that Columbia had cut all ties to the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), the consortium of universities conducting the research.

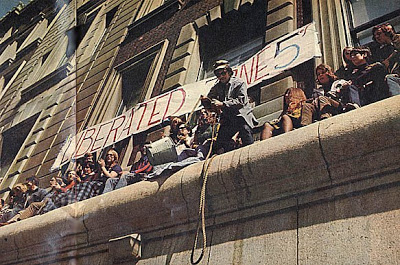

Tensions had been building for a long time. But in a swirl of events, starting with a rally at noon, April 23, 1968, students spontaneously rushed to Morningside Park to tear down the fence around the construction site, and then ended up occupying Hamilton Hall, the main undergraduate classroom building, with Dean Henry Coleman in his office. (A day or so later, the black students asked the dean if he was hungry, and suggested that he go get lunch across the campus, never saying he was released, so as to avoid any impression that he had been held hostage in the first place.) In the middle of that first night the black students in the Students Afro-American Society asked the white students, led by Students for a Democratic Society, to leave: the black students would hold Hamilton Hall on their own, and they invited the white students to take over their own building. And they did, with great enthusiasm. In the end, four more buildings were occupied, including the president’s office in Low Library – which is where I spent that week.

Once we were ensconced in Low, we tried to keep the office suite as clean as possible, considering that it held about 125 people, and we set up cramped living quarters. We also dug out the files on the IDA that proved the university’s complicity and spirited away copies to expose the truth in the underground press.

The faculty tried to intervene and negotiate, and it soon became obvious, no matter what kind of maneuvers by President Grayson Kirk, that the gym and the defense contracts would be dead. In the end, one demand remained the thorniest: amnesty. We felt that we would not accept punishment for doing the right thing, and that if the university wanted to punish us that they should just go ahead and do it, but that we didn’t have to agree to accept it in exchange for . . . being right.

According to former Deputy Mayor Sid Davidoff, the city urged the university to grant amnesty. That would isolate Mark Rudd and his band of radicals, Davidoff had explained his strategy, and he warned that the police were frustrated and itching for blood, “chewing on their nightsticks” in buses for days. Once they were unleashed, he had explained to the university administration, they could not be controlled. Meanwhile, Yale President Kingman Brewster and others called Kirk, telling him to stand firm, that if Columbia gave in to amnesty, other universities would collapse in the face of student rage – another version of the domino theory.

Kirk finally did send in the cops. The black students, advised by lawyers, told the police that they would not resist but that they would not leave Hamilton Hall without being arrested, and they allowed themselves to be cuffed and taken away with no violence. Their approach prevented black students from being brutalized, a spectacle that could have ignited Harlem, and their charges were limited to criminal trespass and no more.

The white students in the other buildings offered passive non-violent resistance of various forms – and as a consequence they were severely beaten. Over 700 were arrested that night, and over a hundred injured, as the cops charged through faculty and students outside the buildings and bloodied many of those inside.

Events spiraled after the bust into a strike involving the entire university, including faculty, and to other occupations, demonstrations, police riots, and negotiations, going on through the next academic year and beyond. The gym was history, the war research was canceled, and Columbia went through a process of rebuilding itself and, with other universities, reforming higher education to include more democratic governance involving students and faculty, innovations such as black and ethnic studies and women’s studies, and a deeper sense of accountability. The discourse of “diversity” and “multiculturalism” arose from the revolts of Columbia, as well as other schools, to the dismay of the right-wing to this day.

So, forty years later, we came together on the campus from April 24th to 27th with current students, faculty and community members to commemorate the revolt. The “wrinkled radicals,” as the student newspaper called us, reconnected and exulted, sensed our mortality and mourned, perhaps all to be expected at any kind of reunion. We wanted, as Gus Reichbach, now a judge in New York, underscored, to show today’s students that it’s possible to live lives committed to social justice – and still have fun. But we also wanted to discover the deeper significance of the strike and its legacy. With the country embroiled again in yet another immoral war and Columbia once again expanding into Harlem, the similarities and differences were crying out to be explored.

The day before the conference, the New York Times published a personal reflection on the strike by critically acclaimed novelist Paul Auster, “The Accidental Rebel.” He had been part of the occupation of the Math building, and he too would read at “Voices of 1968.” Auster constructed the little essay around the idea that 1968 was “the year of craziness, the year of fire, blood and death . . . and I was as crazy as everyone else.” He went on to observe that “Being crazy struck me as a perfectly sane response to the hand I had been dealt,” which was the threat of being drafted into a war that “I despised to the depths of my being.” He reflected on the gym, the landgrab, the backdoor apartheid quality, but for him the war was at the center of his own revolt. He didn’t recant, had no regrets, and “was proud to have done my bit for the cause,” even though he felt that not much had been accomplished, considering that the war continued to drag on for too many more years. And then, noting that he would not say “the word ‘Iraq’” (and by not saying it, did just that, in great Jonathan Swift tradition), he ended his piece with humorous defiance that “I am still crazy, perhaps crazier than ever.”

Auster’s “craziness” managed to surface periodically through the conference panels on Vietnam and Iraq, on the ethics of protest, race, the legacy of the student movement, the emergence of the women’s movement, and more. Longtime activist Tom Hayden, also a veteran of Math, objected to the essay, regarding Auster as trivializing the protest as insane, an aberration, and not a political eruption. The next day, philosopher Akeel Bilgrami regarded Auster’s craziness differently, describing it as part of Erich Fromm’s observation that, in an insane society, one must become “crazy” to become sane, one must disrupt the bland, grim normality of the lunatics in charge. In fact, Erich Fromm spoke at the counter-commencement held by protesting students in 1968, so Bilgrami may have certainly captured one aspect of the spirit of the age. At the same time, Ray Brown, one of the leaders of the black students in Hamilton Hall, also objected to considering what the African American students had done as “crazy.” As the conference would reveal, the black students felt they had to act with utmost sanity to undermine racist expectations. All of this was quite a bit of play for a little personal reflection – but it was, after all, the only voice in the New York Times for what we had done, so a lot more hung on a short essay than anyone might otherwise note, and the controversy was intense.

Indeed, we met with almost the same intensity as we did 40 years ago – minus the cops. But much of what took place was unusual, and a bit surprising. In our self-reflection, “crazy” was able to take on all sorts of meanings.

Most electrifying was a multimedia re-creation or tableau called “What Happened” that presented a narrative of events, starting on April 23, 1968, with participants describing their experiences at each juncture. Eventually, this narrative-testimony will be brought together as an audio and textual document, hopefully with additional accounts by those students who supported the university administration, and others, such as the police and surviving professors. But even with the dozens of those who took part in the strike testifying at this event, we learned much of what really took place.

For example, the women’s movement was just beginning, and Columbia would be one of the last major protests where male monopoly of leadership and traditional gender roles went unchallenged. It was impossible to revise those dynamics entirely today – Columbia was all-male then, and we could not change that fact – but we were able to highlight the role women played and the rumblings of imminent eruption. For instance, a key juncture in the rebellion was when the demonstrators on April 23rd found themselves locked out of Low Library, the main administration building, and were frustrated in their attempts to confront the university administration. At that point, accounts note that anonymous cries went out, “To the gym! To the gym!” whereby the crowd headed to Morningside Park to tear down the cyclone fence at the construction site. At “What Happened,” we learned that those shouts were not anonymous: Bonnie Offner Willdorf and Ellen Goldberg announced that they had been the ones to re-direct the demonstration: “It was two women who called out ‘To the gym! To the gym!’” Two women acting “crazy,” violating the decorum expected of Barnard students, and they led the auditorium once again in cries of “To the gym! To they gym!”

But it was race relations that was the most volatile, then and now, and the revelations were the most startling – which is what drove Paul Spike to write his essay in response. In 1968, as I outlined earlier, there were two main groups of students driving the protest, black students led by the Students Afro-American Society, and the rest of the students, overwhelmingly white, led by Students for a Democratic Society. During the upheaval, there were two distinct perceptions of strategy and tactics; and afterward, there were two different streams of experience and memory. After the bust, we went our separate ways, politically and socially; and now the conference finally allowed these two streams to converge: black and white came together, and we came to understand each other far better than ever before.

Read the rest of this article here. / Op Ed News / May 27, 2008

Also see [A. Embree : 1968 Columbia Student Revolt Remembered in New York, / The Rag Blog / May 3, 2008

The Rag Blog