Silence in Chiapas:

Zapatista rebels ‘on vacation’

Is a new uprising on their agenda or does the Zapatista Army of National Liberation just want to be left alone?

By John Ross / The Rag Blog / January 21, 2010

MEXICO CITY — The pitch-black night suddenly came alive with darting shadows. The slap slap of rubber boots against slick pavement echoed throughout the hushed neighbors on the periphery of town. Sleepy chuchos stirred in the patios, stretched and bayed, their howls catching from block to block, barrio to barrio.

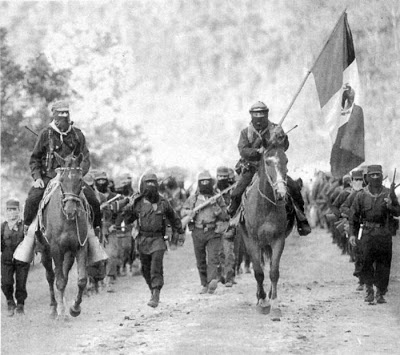

Across the narrow Puente Blanco, down the rutted Centenario Diagonal, up General Utrilla from the market district, dark columns jogged in military cadence. With their faces canceled behind ski-masks and kerchiefs and their collective breath hanging in the still mountain air like vapors from a cruel past many Mexicans have disremembered, the “sin rostros” advanced on the center of the city of San Cristobal de las Casa, the jewel box colonial city that crowns the Mayan highlands of Chiapas, Mexico’s southernmost state.

So it began, the Zapatista rebellion, January 1, 1994, in the first hour of that beacon of globalization, the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Sixteen years later, past midnight on January 1, 2010, a year in which many sense that the 100th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution will be celebrated with new uprisings, there were no darting shadows or dark columns of Zapatistas marching on the center of San Cristobal and the howling of the dogs, rather than alerting the city to the arrival of the Indian rebels only marked the passing of a desultory drunk tottering home to sleep off the excesses of New Year’s eve.

Each year since that first New Year’s, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) has commemorated its brief takeover of San Cristobal and six other municipal seats in southeastern Chiapas with militant speeches and fiestas thrumming with the herky jerky rhythms of the rebels’ favorite cumbias, sometimes at the “Caracol” or public center in La Realidad on the edge of the Lacandon rainforest but more often at Oventic in Los Altos of Chiapas, 45 minutes as the crow climbs from San Cristobal.

But as 2010 tolled in, a hand-lettered sign posted to the gate of the highland Caracol advised visitors that Oventic would be closed to visitors until January 2nd. At the Ejido Morelia in the lowlands, a note tacked to the Caracol fence proclaimed that the rebels were “on vacation.” Three other Caracoles — La Garrucha, La Realidad, and Robert Barrios (in the north of the state) — were similarly locked down tight for the first time since that first January 1, a clue that no new revolutions are brewing, at least here in the Zapatista zone, as Mexico ushers in the centennial of its landmark revolution.

Punctuated by long silences, the Zapatistas‘ resonance has plummeted precipitously in the first decade of the new millennium. The Indians’ struggle lost a great deal of relevance after much of the urban left abandoned the Zapatista cause when the Mayan rebels’ quixotic spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos lashed out at the left candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in the fraud-marred 2006 presidential elections and refused to support the millions who marched to rectify the results. The EZLN has never been able to recapture the initiative.

Since then, the Zapatistas have retreated to their villages and Caracoles, quietly defending their hard-won autonomy and only occasionally seeking to stir support in the outside world.

As an adjunct to their yearly in-house marking of the occupation of San Cristobal and the promulgation of the first Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle back in 1994, the EZLN and its supporters in the “Other Campaign” — originally formulated in 2006 to thwart the electoral left — have held Christmas week seminars to which European intellectuals are invited to present papers praising autonomy and the rebels’ fierce resistance to globalization.

Last year’s “Fiesta of Digna Rabia” (“Dignity & Rage”) focused on the Mexican government’s criminalization of social protest and the defense of Zapatista conquests. In 2008, the conclave was dedicated to the struggle of Zapatista women. The word fests were invariably followed by visits to the Caracoles and much cumbia dancing.

The 2010 edition unfolded at the University of the Earth, an alternative learning place on the fringes of San Cristobal. No Zapatistas were in attendance. Among the invitees were international “anti-systemics” such as Cristine Kummer, an East Indian writer on the demons of globalization who has long lived in Tunisia. On her first visit to Chiapas to sample in person the social movement that she describes as “the most important of our time,” Kummer was disappointed to find Zapatista communities closed down to visitors.

Although the mandatory French intellectual Jerome Basent was on hand (the symposium is dedicated to the memory of Andres Aubrey, a French anthropologist beloved by the Zapatistas), headliners like Shock Doctrine guru Naomi Klein who was on hand last year, and French-English memoirist John Berger, who attended in 2007, were nowhere to be seen (Berger did send along a chapter of a new book denouncing the world as a prison.)

But the featured no-show was the near-mythical Subcomandante Marcos who has not been seen or heard from since he took the microphone to lambaste Lopez Obrador at last year’s Digna Rabia fiesta. In fact, the Sup has been missing in action for a full year now and the endless stream of communiqués that he so assiduously cranked out in the first years the EZLN was on public display has dried up.

Despite the sort of conflictive year for Mexico that Marcos used to relish commenting upon, the Subcomandante did not issue a single public word in 2009. When the economy collapsed, driving Mexico into its steepest downturn since 1995 (for which then-president Ernesto Zedillo blamed the Zapatistas), the Sup remained speechless.

As the left Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) he so detests was riven asunder by internal conflicts and his nemesis Lopez Obrador relegated to roaming the outback of Oaxaca, the one-time Zapatista mouthpiece held his tongue. When Mexican president Felipe Calderon shut down the Luz y Fuerza power company and moved to privatize it, putting 42,000 members of the Mexican Electricity Workers Union in the street, no note of solidarity was forthcoming — despite the electricistas‘ installation of power lines that brought light to Zapatista communities in the jungle.

This December, Marcos’s mother (if he really is Rafael Sebastian Guillen Vicente) dropped dead at the Mexico City airport. No memorial announcements were published in Mexico City newspapers as is funerary tradition here. Now as the 100th anniversary of the Mexican revolution looms, Sup Marcos, who once postulated a new constitutional convention in 2010, remains stonily mum.

Actually, the Zapatista leader’s reticence is not unique. In 1995, after Zedillo vetoed the San Andres Accords on Indian Rights that guaranteed limited autonomy to Mexico’s 20,000,000 indigenous peoples, an enraged Marcos went silent for 18 months. After the accords were gutted by the Mexican Congress in 2001, the Zapatista spokesperson clammed up for nearly three years, finally breaking his vow of silence to proclaim the opening of the Caracoles in 2004. But this time around, Marcos’s absence feels like it is forever.

Whether Marcos, who is really only his mask, has abandoned his persona or retired from revolution or is lounging at a café on the left bank of Paris — or worse — his disappearance from the public arena is the subject of much perplexed speculation.

Although EZLN communities in the highlands and the jungle are still quarreling with their neighbors over land the rebels took back from Chiapas ranchers in 1994, the EZLN is no longer under siege from the Mexican military which now limits itself to perfunctory patrols in their territories. Nonetheless, the enemy may be more insidious.

Whereas Chiapas was once governed by tyrants like Roberto Albores who delighted in violently dismantling autonomous communities, the present governor, Juan Sabines, who was elected on the PRD ticket, is always inviting the Zapatistas to dialogue and promulgates flawed Indian Right laws. To burnish his image of benevolence, Sabines liberally spreads around large sums of cash to the very venial Chiapas media.

The largesse has even found its way into unlikely pockets: La Jornada, Mexico’s only left daily and a vocal champion of the Zapatista cause for the past 16 years, is now allotted generous subsidies for running Sabines government publicity and publishing gacetillas, press bulletins that are published as if they were news stories. The fresh cash is a welcome source of revenue for La Jornada in a recession year when Mexican newspapers are being hammered, the management explains.

The Chiapas governor is a nephew of Mexico’s most popular romantic poet, Jaime Sabines, and the son of a former governor — unlike his father, also Juan, who is deemed responsible for the slaughter of dozens of indigenas at Golonchan in 1979, Junior has no Indian blood on his hands — yet.

Juan Sabines aligned himself with the PRD after his own party, the once-and-future ruling PRI, rejected his candidacy. Since his narrow victory in the 2006 election, the governor has veered to the right, meeting frequently with Mexican President Felipe Calderon of the conservative PAN and has broken all ties with Lopez Obrador who once hailed his victory as a triumph for the electoral left.

Last November, as rumors generated by Sabines’ media machine swirled that the Zapatistas would rise on the 20th of the month, the 99th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution, the Chiapas state congress under the baton of the Governor installed a commission to “dialogue” with the Zapatistas. The Chiapas “prensa vendida” (and La Jornada) reported that the rebels had approached Sabines seeking legal recognition in order to finance social projects.

News of this supposed deal provoked serious discombobulation among Zapatista supporters. Gloria Munoz, a columnist for La Jornada (“Los de Abajo“) who spent many years living in rebel communities, received worried e-mails from the German solidarity movement demanding an explanation of the reported Zapatista sell-out to the “mal gobierno” (bad government.) Munoz and Magdalena Gomez, once an advisor to the EZLN during negotiations of the San Andres Accords and also a Jornada contributor, rejected the story as a Sabines’ hoax — the Zapatistas‘ most remarkable achievement has been their autonomy and Zapatista autonomy was not for sale, they wrote.

Indeed, the EZLN soon set the record straight. Although the Juntas de Buen Gobierno (JBGs) that administrate Zapatista autonomies and are based at the five Caracoles had not been very garrulous in 2009, all five juntas under the pen of the Oventic comrades issued an energetic denial of Sabines’ “lies” which they termed “a counterinsurgency plot to confound public opinion…we have never asked for crumbs from the mal gobierno.” After 16 years of lucha (struggle) for their autonomy, the Zapatistas would never sell out.

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation is still technically at war with the Mexican government although few shots have been fired in years. The rebels’ refusal to deal with the State was sealed in 2001 after Congress — with the vote of the PRD — deep-sixed an Indian Rights law drawn from the San Andres Accords. The accords, which were signed off in February 1996 by Zedillo’s representatives and would have guaranteed autonomy over everything from land use to the way Indian communities select their authorities by “uses and customs,” were brokered by a congressional Pacification and Reconciliation Commission, the COCOPA, that has long since fallen into irrelevance.

Now, in a PRD ploy to revive a dead horse, the current COCOPA president Jose Narro Cespides flew into San Cristobal for the 16th anniversary of the rebellion issuing conciliatory statements to the rebels and taking out newspaper ads pleading with the Juntas de Buen Gobierno to receive him in the Caracoles. The EZLN, which has long regarded the COCOPA as an emissary of the mal gobierno, were not moved. Like Luis H. Alvarez, the 90 year-old government peace commissioner who spent six years cruising the jungle and the highlands without ever actually talking to a Zapatista, Narro Cespides returned to Mexico City unrequited.

Does the rebels’ silence mask a surprise for 2010? Is a new uprising on their agenda or does the Zapatista Army of National Liberation just want to be left alone? Zapatologists such as this writer have always been notoriously off the mark in trying to predict what the compas will do next. Stay tuned.

[John Ross will be trekking Obamalandia with his latest cult classic El Monstruo — Dread and Redemption in Mexico City (“a gritty, pulsating read” — New York Post) from February 4-May 1. Send suggestions of possible venues (particularly CHICAGO and U.S. South) to johnross@igc.org.]

A quick recollection. New Years Eve, I had ordered 50 cases of beer for the gran fiesta at my barra y pizzaria in San Cristobol. We had a house band "Pirox Nohox" (big ass in Mayan) and two other bands. We found out that our friend, an Italian woman who was managing another bar "El Circo" would also have three bands. We set out to see Maria to offer to swap bands as they