Once, in an altered state, Duane and I climbed a fire tower in the night and looked over many square miles of pine trees under the stars.

Michael James self-portrait, The Castle in the Sky, Chicago, Illinois, 1975. Photos by Michael James from his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.

[In this series, Michael James is sharing images from his rich past, accompanied by reflections about — and inspired by — those images. These photos will be included in his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.]

1975 jumped right off with a joyous New Year’s Day People’s Dance and Celebration at the Midland Hotel featuring the power-rock trio Fast Eddie, a benefit for Rising Up Angry’s “People’s Legal Program.”

The very next day, January 2, the Menominee Warrior Society took over the Abbey, the abandoned Alexian Brothers Novitiate in Gresham, Wisconsin. My friend Duane Teller was the young warrior who ran through the snow-covered woods bringing that news to the reservation town of Keshena and beyond.

Pictures from the Long Haul

At the Midland Hotel a month later, as I was setting up for another People’s Dance, a stage riser fell over and landed on my right foot. Even my combat boots couldn’t prevent four metatarsal bones from breaking. Before going to the hospital, I spent hours icing my foot and talking with Bill Martin and Carolyn Grisko of Northeastern University’s WZRD. The “Wizard” recorded our events and then sent them out over the FM waves.

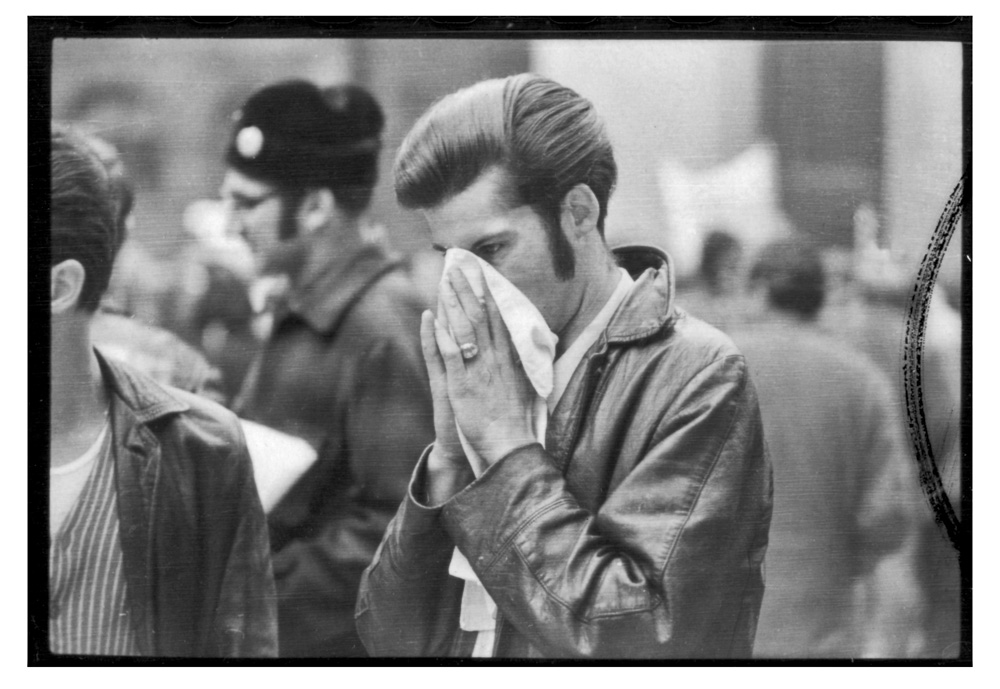

This was not the first time I suffered an injury at a People’s Dance. On January 17, 1971, my jaw was broken at Alice’s Revisited on Wrightwood. Alice’s Revisited was a hippie restaurant/juice bar/entertainment venue run by Ray Townley. RUA enlisted the bands Wilderness Road and Yama and the Karma Dusters to play a benefit there. Richie Faluna, a 79th street greaser hanging around in those days, was fucked up on downers and spitting in my face as we removed him from the building.

I gave him a push that sent him sprawling on the ice-covered sidewalk. I was turning to say, “Get him the fuck out of here before the pigs come” just as he came from behind, catching me with a solid hook — a sucker punch from the blind side. My left jaw seemed to explode — to this day my memory brings up the image of a pack of Chinese ladyfinger firecrackers going off in my jaw.

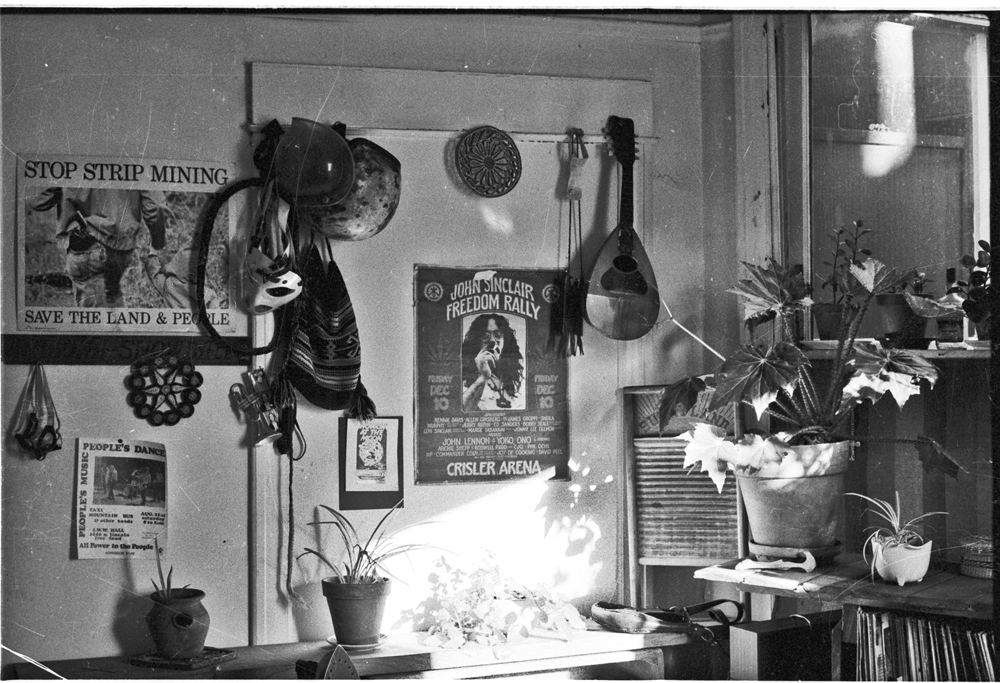

I recuperated from my various wounds in the shelter of my new crib at 4431 North Greenview in Uptown, an apartment I dubbed the “third floor castle in the sky.” I got the apartment from friends who were running smoke from Quebec across the border into Vermont and beyond. Since I was uptight and paranoid about being busted by the cops even when I was just driving around town I was awed by their daring occupation.

During this time I embarked on a spiritual regeneration, reading Baba Ram Das, Carlos Castaneda, Maria Sandoz’s biography Crazy Horse, and Black Elk Speaks. I did yoga and contorted stretching, looking west through the living room windows at tree branches and some very beautiful Chicago sunsets.

I got a 4-foot square, sheet metal goldfish pond, filled it with fish and plants, and water trickling down lava rocks and put it beside my pallet on the floor. I listened to jazz-fusion: Weather Report and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, great sounds for healing my body and developing my spirituality. I had thoughts of a “comprehensive consciousness.” And I cooked, often a pot of beans with fatback (salt pork), brown rice, broiled chicken with sage, and a salad with freshly made dressing.

Many folks passed through the doors of this abode to visit or stay awhile. They included my kids Jesse, David, and Coya, friends and girlfriends old and new, people from Chicago and beyond. Once a friend smoked a cigarette in my bedroom and we awoke to the mattress on fire and the room half-filled with smoke. I dumped the mattress into the pond. The landlords tried to kick me out afterwards.

My roommates included guys I knew from Uptown. Paul Stamper was out of Olive Hill, Kentucky. His dad, Clayton, a heavy juicer, stayed there, too. Clayton’s help and skills were invaluable when we started work on the Heartland Café. And there was Art Davis, a big guy and the Heartland’s first cook; his childhood nickname “Chink” bothered me. Art’s Japanese mom ran a restaurant on Clark near Fullerton. He didn’t know his hillbilly GI dad, who had met his mom in Japan at the end of World War II.

And there was Junebug: Jack “Junebug” Boykin from Jackson, Tennessee, who was part of the Goodfellows, JOIN Community, and early RUA. He also helped open the Heartland, and was my mentor in country music, clothing style (leather jacket, Italian knits, pointy-toe shoes), and street behavior and etiquette. We appear in a scene together in Stony Island, Andy Davis’ 1978 film about black and white kids starting a band together on the South Side. Junebug also appears in Mike Gray’s American Revolution Two, in a scene where, as a member of the Young Patriots, he engages in dialogue with Black Panther Bobby Lee.

And then there was my friend Duane Teller. I met Duane through his brother Daryl when I was living on Spaulding off Wrightwood in Logan Square, after my first wife Stormy and I broke up. It was there I experienced my emotional return, a coming back to life, after the breakup. I associate my leap back to confidence and return to good times with a sunny afternoon spent listening to Graham Nash’s tune “I Used to Be a King”: “Someone is going to take my heart, but no one is going to break my heart again.”

Daryl was hanging out at the statue on Logan Blvd. at Kedzie. I was selling Rising Up Angry when he and I began talking. He took me to his house nearby, where I met Duane. Duane was in the act of butchering a live chicken he had found who-knows-where.

I’m not sure if it was because I had helped the farmer down the road as a kid in Connecticut butchering both cows and pigs during my 4H Club days or the time I spent working in a butcher shop at age 14, but in any event Duane and I became fast friends. We shared our histories and partied together. I followed his adventures as he and other young Indians toured around the country in those wild days of the American Indian Movement (AIM).

Once when returning to the castle in the sky I came upon 22 — yes, 22 — young Indians camped out. In addition to Duane there was Kenny Little Fish, who carved his name and a fish in the rough-hewn, orange-painted rocking chair I had hauled back from Durango, Colorado (and these days occupies a place of honor in our dining room). There was Curtis McFall, who stole stained glass windows around town and whose dad was a renowned tattoo artist at the Cliff Raven tattoo parlor.

And there was the late James Yellowbank, a long time activist I came to know and appreciate. He swiped my guitar, then over decades regularly apologized for having done so. Also in the apartment was Paul Skyhorse, probably the leader; for a time he was implicated in the murders at an AIM camp outside of Los Angeles, where actor David Carradine (of Kung Fu fame) hung out. Those charges turned out to be another government conspiracy to frame AIM leaders and he eventually won the case.

In April of 1975 Cooperative Energy Supply brought in the Native American band XIT, whose members were from various Indian tribes, for a series of benefit concerts for AIM and RUA. During 1975 I made several trips north to the Menominee Reservation. People I met on the res were using the word “horse” as in “hey horse,” an expression of friendship I really liked.

I had fun times with fellow “horses” Duane and his family, my son David, good friend and artist Lester Doré, and others. Black coffee, canned vegetables, white bread, and meat: no fresh vegetables to be found. We took traditional sweats and I, not wanting to be called a chicken, stayed until I thought I would die waiting to get out and jump into the nearby Wolf River.

Once, in an altered state, Duane and I climbed a fire tower in the night and looked over many square miles of pine trees under the stars. Near a garbage dump already visited by many deer, I chased a porcupine. Duane’s sisters Rory and Dora encouraged me to get some quills, accomplished by hitting the animal with a t-shirt. All this was a little scary in that altered state.

We slept on cots in the unfinished cement basement of a 50’s-era government house. In late winter of 1975 we visited The Abbey, a short-lived radio station in Keshena, and stood fence-side talking to a small herd of horses with shaggy coats. With my cast, crutches, and walking cane gone (though wearing the same combat boots I wore when I broke my foot), I took my first tentative strides at running again. That was a very wonderful moment.

Back in Chicago, Rising Up Angry was in transition. Steve Tappis left the organization and town, having come to the conclusion that The Revolution wasn’t going to happen. Bob Lawson returned to California to work as the labor guy in Tom Hayden’s Democratic primary run for U.S. Senator. In April the Viet Nam War came to an official end and the last issue of Rising Up Angry, March 16-April 16, 1975, appeared.

It was thin, with a center spread on International Women’s Day March 8, and the words “The rising of the women is the rising of us all” on the cover. The Serve the People programs — free legal and health clinics, as well as Cooperative Energy Supply and the People’s Sports Institute — began to wind down.

For me, this transition time was seven weeks of moving around, learning and observing, and thinking about what was next. July 1st I headed west with Jake Manning, who was working on an ultimately never-completed film about the IRA (Irish Republican Army).

We drove through Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River country and stopped in Macomb, Illinois, to visit with Bill Knight, publisher of the political-cultural magazine Sunrise. We crossed into Nebraska at Plattsmouth and slept on a bluff overlooking the Missouri River. The radio was full of news about floods and crop loss in Minnesota and North Dakota, the FBI raid on AIM at Wounded Knee, and Muhammad Ali winning a title fight against Joe Bugner.

Rolling west we stopped in Nevada, where we played 25-cent slot machines at Gear Jammer’s Inn, enjoyed ice cream at Mary & Moe’s in Fernley, and stopped for car parts at a junkyard in Reno. July 3rd we arrived in Loomis, California, at the home of my friend, performer Jack Traylor. He’d just finished doing time for drug possession in Lompoc Prison. That night, in the 1975 Sierra Club Engagement Calendar I used as a journal, I wrote a poem, “A Fourth of July Message to My People,” which was later published in Sunrise.

A Fourth of July Message to My People

America

It is the eve fourth

of our bicentennial

And we find that the bottle has let us down

We are still singing ‘trouble in mind’

But the sun will shine in our backyard someday

And in the front yard too

In fact right in thru the front doorWe will no longer sing more songs of sorrow

than of joy

For the time will come

When we the people of this land

In unison with all the world over

Will let our collective lights shine!

During those weeks in California’s warm embrace I visited many friends and places and had myriad experiences. I visited Barbara Martin, whose parents had canoed the waters of the Thames River by New London, Connecticut, to protest nuclear submarines being built at Electric Boat. I saw the Pickle Family Circus in Golden Gate Park, and saw the Mathews family in Los Gatos; they had nurtured me after my auto accident on Highway 101 back in 1960.

I returned to the Carmel Highlands, which felt like going home. In San Francisco I visited my sister Melody and her friends in the San Francisco Mime Troupe, joining in their Survival Boogie fundraiser. And I saw many friends I knew from both UC Berkeley and SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), including Hamish Sinclair, Terry Roberts, Kim Diamond, Gayle Markow, Lincoln Bergman, Nigel Young, John Thomas, and Jim Russell. I saw my JOIN and Rising Up Angry comrades Bob Lawson, Nori Davis, Junebug Boykin, and Susan Ring.

At a Rolling Stone party, which I attended as a guest of the former Chicago Seed editor Abe Peck, I met Paul Krassner of The Realist and the well-known war resister David Harris. The party featured a champagne punch with a tank of laughing gas next to it.

I ran a lot, swam in rivers and pools, and jumped into the wild Pacific. I read Han Suyin’s The Morning Deluge on Mao and the Chinese revolution, saw the movie Nashville, and did peyote. I drove a Volvo loaner from my friend and investigative reporter Angus McKenzie up to Ukiah to visit actress Timi Near, her singing sister Holly, and their family.

In Oakland I talked with David Du Bois, the son of W.E.B. Du Bois and at the time the editor of Black Panther. I visited The Island restaurant in San Francisco and a restaurant/music venue in Santa Cruz called The Catalyst. Both left a dent in my consciousness, and surely influenced my next life choice.

With David Meggyesy, my retired pro-football player friend, I drove to Durango in his green VW bug. I was impressed with Mormon oases of green in Utah. I spent a couple of weeks outside Durango in Hesperus, during which time Dave and I took a ride down to New Mexico. We visited the XIT guys in Albuquerque, and then Wilbert Tsosie, a Native American activist who was fighting a coal-fired power plant in Farmington. I shot some 8mm film in Tierra Amarilla, where Lopez Tijerina had raided the courthouse in a battle over land grants back in the day.

On a second solo run to New Mexico I soaked in an abandoned mineral bath, then visited Angus’s brother Jim McKenzie in Placitas and rode his horse Maria in the desert until she ditched me. After I came back Jim fixed a delicious dinner of fresh-killed rabbit. Later I took in a wonderful Willie Nelson concert at an outdoor venue in Santa Fe.

In Denver I checked out SDS and JOIN pal Rennie Davis who at the time was involved with the Guru Maharishi. I was impressed with their operation, though their own inner organizational culture left me ill at ease. I found my former squeeze and fiancé from my Lake Forest College days, Lucia Crossman, who by now lived in Louisville.

On August 19, I caught a ride to Joliet with guys from Janesville, Wisconsin, then hitchhiked, getting first a ride with a carpenter and then another with a Xerox salesman who left me off on Cicero Avenue back home in Chicago. I took a bus, the El, and then after a short walk I was back at the castle in the sky. Chink and I hit Chester’s Hamburger King for a meal.

In Rising Up Angry, I proposed we use the building we owned as a community center called Rising of Us All. Someone on the West Coast had turned me on to the Peckham Experiment, a 1926-1950 community building effort in London where much of the activity was focused around a swimming pool. They encouraged friendship, cooperation, and activities that promoted good health for the working class. In the end, my proposal to keep the building and change the RUA name didn’t happen.

I continued to frequent the Japanese greasy spoon, Chester’s Hamburger King. Bill, a veteran of the WWII internment camps that locked up Japanese Americans, would set me up at a table in the back. This became my morning note-writing den where I began to plan my next moves. These involved someone I had met on October 3, at a Holly Near concert for the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU).

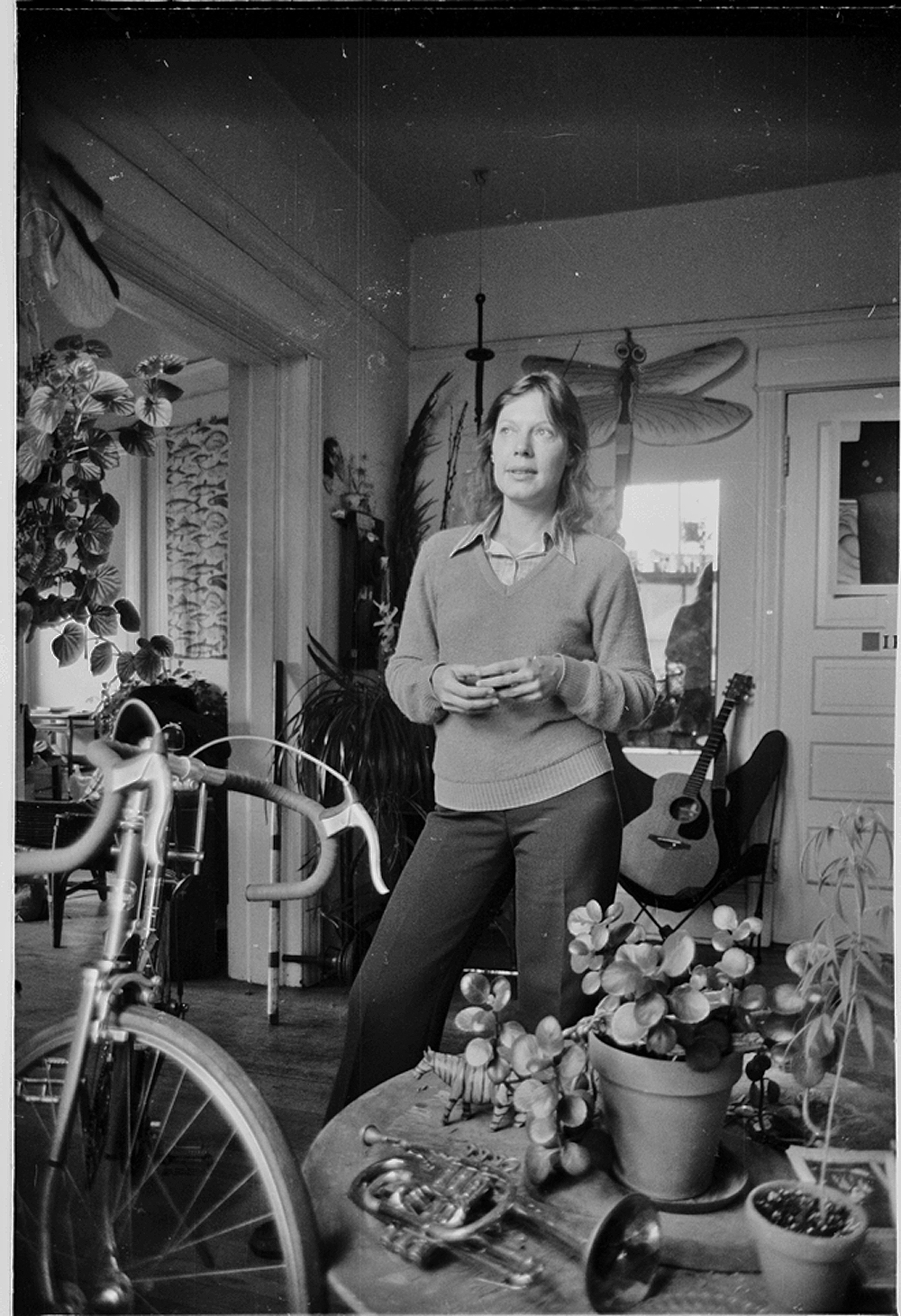

At that concert, a few of us at a table on the mezzanine were smoking a joint when a handsome young woman approached and said, “Can I get a hit?” Kathleen Hogan, aka Katy, was from Chicago’s southwest side, a Mundelein graduate, had traveled to Mexico, had once hopped a train to New Orleans to begin a trip to Peru, and was both a teacher with the Associated Colleges of the Midwest and an activist with the CWLU.

I resounded with “Sure, come on, join us!” and proceeded to invite Katy to play volleyball the next Sunday at River Park, where coed teams from various political organizations engaged in “sports for the people.” After a long day of volleyball, we took in a country band at Pam’s Playhouse at Leland and Clark. This was the beginning of a partnership that has lasted, in evolving forms, the rest of my life.

By May of 1976, Katy and I, along with Stormy, began work on our vision of a community center and culinary business. On August 11, we opened Sweet Home Chicago’s Heartland Café.

Find more articles by Michael James, including previous installments of this series, Pictures from the Long Haul, on The Rag Blog.

[Michael James is a former SDS national officer, the founder of Rising Up Angry, co-founder of Chicago’s Heartland Café (1976 and still going), and co-host of the Saturday morning (9-10 a.m. CDT) Live from the Heartland radio show, here and on YouTube. He is reachable by one and all at michael@heartlandcafe.com. ]