Sonny gave me this advice: ‘Just make sure you’re not hanging out in these same bars 20 years from now.’

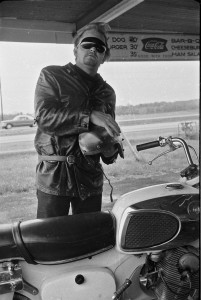

The Appaloosa Mother, South Dakota, August 1967. Photos by Michael James from his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.

[In this series, Michael James is sharing images from his rich past, accompanied by reflections about — and inspired by — those images. This photo will be included in his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.]

A treasured traveling moment forever: chasing the sun, speeding over and through the rolling hills of eastern Iowa. It was August 1966. Bob Lawson and I left Chicago, crossed Illinois and the Mississippi River, and rode into Iowa on my newly acquired 1964 Triumph TR6 motorcycle.

Pictures from the Long Haul

We were on our way to the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) convention at a Methodist Camp near Clear Lake, Iowa. On one stretch of road I took the bike up to 112 mph, a once-in-a-lifetime experience. By nightfall we were watching stock car races and a demolition derby in Mason City before heading on over to the Camp.

While we were at the convention news came that cops from the scandal-ridden Summerdale District in Chicago had busted the JOIN office. Court proceedings later proved the police planted pot in the office before ransacking it and busting my sister Melody, who was working in the office at the time of the raid.

In response to concerns and outrage expressed by the SDS body I quoted organizer Joe Hill of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW): “Don’t mourn, organize.” Joe had said them as he stood before a Utah firing squad on November 19, 1915. The day I repeated his words I was elected to the National Interim Committee, the closest thing SDS had to official leadership.

Back in Chicago I followed up on the invite I’d given to my new acquaintance, Bernardine Dohrn, to take a ride on my motorcycle. A University of Chicago law student, Bernardine was working with the LSCRG (Law Student Civil Rights Group), part of the justice-seeking National Lawyers Guild (NLG).

She took me up on the offer and we toured Chicago’s backstreets. Not long afterwards, without asking her first, I signed her up in SDS — a unilateral act she did not appreciate. Luckily for me, this didn’t stop us from spending a lot of time together.

At Christmastime in 1966 she and I headed to Berkeley in a drive-away car we were delivering to the Coast. We stopped on the US-Mexican border between Douglas, Arizona, and Hermosillo, Sonora. Before I knew it we were in Mexico.

This was problematic, as I had a few joints in an envelope in my attaché case. Crossing back into the States we encountered a border guard who had worked at Pontiac, an Illinois prison. I engaged him non-stop in conversation. When he opened my case, the magazine Studies on the Left stared him in the face. He fingered through the back compartments, closed it up, and we said adios.

Bernardine and I headed back to Douglas. The next morning we walked back across the border for breakfast, had our picture taken by a street photographer, and then continued on to California.

In late winter of 1967 Bernardine moved to Barry Street on Chicago’s Northside. She studied long hours for days, preparing for her law school exam. One night she took a break when Junebug Boykin, Bobby Joe, and I visited her while we were tripping on LSD. She spent much of the evening laughing as we wild boys engaged in a prolonged psychedelic Jell-O fight around her dining room table.

Days were spent organizing around issues of housing, welfare, and the police. We put out a newspaper. We challenged the city on urban renewal, aka “poor people removal.” JOIN organizers met and befriended local people, learning about them, their families and situations. Marilyn Katz, who’s father was “a high-up” in the Chicago Jewish Mafia, Fran Ansley, Diane Fager, and Gayle Markow organized a food cooperative, where they met a woman named Peggy Terry.

Peggy was originally from Oklahoma. When Studs Terkel interviewed her later, she told him she had been a racist. But in Birmingham, Alabama, she met and married the radical, Gill Terry, and Peggy participated in civil rights demonstrations with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). In Uptown Peggy was on welfare and lived on Clifton with two of her three children.

Peggy and I started The Firing Line, JOIN’s newspaper. A year later I managed her campaign when she ran for Vice President of the United States on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket. Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver was the candidate for President.

In August of 1967 two NFL players from the St Louis Cardinals, Rick Sortun and David Meggyesy, came to Peggy’s house to meet her. Rick and David were into radical politics, and the Cardinals trained just north of Chicago at Lake Forest College. (I wore one of their practice jerseys during my first year of playing football there in 1960.)

When David quit pro football two years later, he wrote Out of Their League, one of Sports Illustrated’s 100 best sports books ever. He mentioned me in the book, we reconnected, and have been lifelong pals.

I also met Frank Fried, a radical steelworker turned music promoter (Triangle Productions) who helped raise money for JOIN. Frank hosted a fundraiser at his home with featured guests the Kingston Trio (including Chad Mitchell) and Harry Belafonte. Belafonte visited the JOIN office the next day, where he was photographed with Peggy.

When I was invited to speak to a group of VISTA volunteers (part of the War on Poverty) in western Pennsylvania. I came back with an old black beater VW someone had given me. I named it Appaloosa Mother.

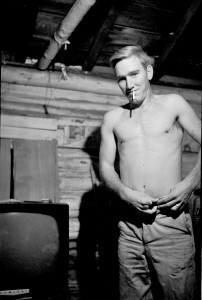

In The Mother I followed Sonny Broom on his Honda motorcycle to LaFayette, Georgia, where he left his bike. We lived it up for a few days — shooting pool, playing with a dog, and smoking weed with a guy named Possum in a back-country cabin. I couldn’t help but notice Possum had lost a few fingers on his right hand. I took pictures of him in his cabin.

Sonny’s mom would later run a bar in Chicago near the Stewart and Warner factory on Diversey. Sonny gave me this advice: “Just make sure you’re not hanging out in these same bars 20 years from now.”

The Appaloosa Mother took me to Miles Horton’s famed Highlander Folk Center in North Carolina for a meeting of the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC). And with Dave Puckett, Virgil Reed, and Peggy’s son Doug Youngblood, it got us to Berea College in Kentucky. There we spoke to a group of extremely unreceptive students; some Black students maneuvered between us JOIN guys and the hostiles. The Black students welcomed our work and protected us in a gnarly situation.

And The Mother took me to down to Southern Illinois University (SIU). I still fondly remember the fried chicken and fresh blackberry pie at Ma Hale’s, on the banks of the Mississippi. Later we stopped in the hills at the edge of the Shawnee National Forest and took in a pastoral scene that included a family of black farmers coming home to their farm in the valley below. It reminded me of a Thomas Hart Benton painting.

Roger Lipmann, SDS’s Northwest regional organizer, gave The Mother a rest when he flew Junebug and me out for talks at Portland Community College, Portland State, Reed, Eastern Washington, and the Universities of Idaho and Washington. I was excited to go to Reed, since my Dad had been a student there for a year in the late 20s.

While at Reed I met Bill Vandercook and stayed in his crib. This is where I experienced a wonderful early morning rainforest wakeup: the smell of incense, the sounds first of a wind chime and then of a Bach flute sonata, and then my first cup of herbal tea. The next day in Moscow, Idaho, after speaking at the University, I had a very different first experience: we went to a gun store where I purchased a pistol. We drove to a canyon outside of town for target practice.

Back in Uptown I met Ronnie Vance aka Ronnie Emerson, a guitar player and pimp from Missouri. I sold him a Fender Jazzmaster guitar, not knowing how valuable it would become. Ronnie moved back to Poplar Bluff, Mossouri, and I took a train there to visit.

It was autumn, cold and drizzly. We engaged in some country life, smoking weed and shooting the shit on the edge of a soybean field in the drizzling rain. Being around this guy and one of “his girls” was interesting for a young guy with an anthropology bent. Later, Ronnie became front man for a band over in Truman, Arkansas, called RC and the Moon Pies, a reference to lunches eaten while out picking cotton.

On another trip out of Uptown Junebug, Bobby Joe, and I went to Boston to pick up a Nash Rambler that had been donated to JOIN. We visited some SDS women I knew and all frolicked on a rooftop calling ourselves Junebug and the Students, posing for our imaginary album cover. Heading home we were stopped cold in Gary, when the Indiana Turnpike was closed by the record blizzard of January ’67. Along with many other stranded motorists we spent the afternoon and night in a common hall at a Holiday Inn.

One of the travelers on a bus from Philadelphia was country blues musician Skip James, headed to Chicago for the University of Chicago’s Folk Festival. I asked Skip to play; he did, but was momentarily interrupted by a young black guy who blasted a Motown tune on a boom box the minute old Skip began to play.

I approached Boom Box and told him Skip was pretty famous and headed to a gig in Chicago. He said, “Cool,” and Skip played a few tunes. When the Turnpike opened in the morning we made it home to Chicago, where we spent the next week shoveling snow.

In March 1967, I was selected to be the SDS speaker at a rally in Chicago’s old Coliseum. The place was packed for an anti-war rally that followed a march down State Street. The speakers included me, Emil Mazey of the United Auto Workers, famed pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock, and Dr. Martin Luther King.

I had met Dr. King briefly in an apartment on the West Side the previous summer, when Rennie Davis and I met with Southern Conference Leadership Council (SCLC) people. King was my hero. I was at the March on Washington in 1963, the first of many times his words brought tears to my eyes. Dr. King’s speech at the Coliseum was one of the first in which he opposed the Vietnam War.

My speech was titled “Break Out and Do It Now!” In it, I challenged people to put themselves in situations that would compel them to change. Hamish Sinclair, an older Scotsman who had worked with unemployed miners in Hazard, Kentucky, helped me put my thoughts into words. Sid Lens, an older activist, introduced me, calling me the “Rudolph Valentino of the New left,” referring to my greased-back hair and leather jacket, which I augmented in classic Uptown street style with a Banlon shirt, A1 Sta-Prest pants, and pointy-toe black shoes.

Before I launched into my speech, I told the crowd of 10,000, “These people taking pictures of you aren’t just photographers, they’re cops from the Red Squad and they’re documenting who is here.” That was only partially true, and after I met the photographer Paul Natkin years later, I regretted having said it. His father was a professional photographer and I happened to be looking right at him when I said those words.

As we left the Coliseum that afternoon, we moved en masse back into the guts of the ogre, the world’s number one imperialist power. We were fired up, committed to changing our country’s policies, ready to break down the negatives, and to tear them up. Our goal was to transform and rebuild a nation we truly loved.

We had many dreams. Ending the War in Vietnam was at the top of our agenda. But first, things in and out of Uptown would get plenty hot.

[Michael James is a former SDS national officer, the founder of Rising Up Angry, co-founder of Chicago’s Heartland Café (1976 and still going), and co-host of the Saturday morning (9-10 a.m. CDT) Live from the Heartland radio show, here and on YouTube. He is reachable by one and all at michael@heartlandcafe.com. Find more articles by Michael James on The Rag Blog.]

Damn Good writing! Keep em’ coming!

A couple of place name corrections: Berea, Kentucky, has only one “r”; and LaFayette, Georgia, does not have a “y” nor a lower-case “f.”

Thanks for the shout-out to SSOC.

Thanks, Steve. I just made those corrections.