The summers of 1967 and ’68 were hot — real hot — and we were in the ‘guts of the ogre.’

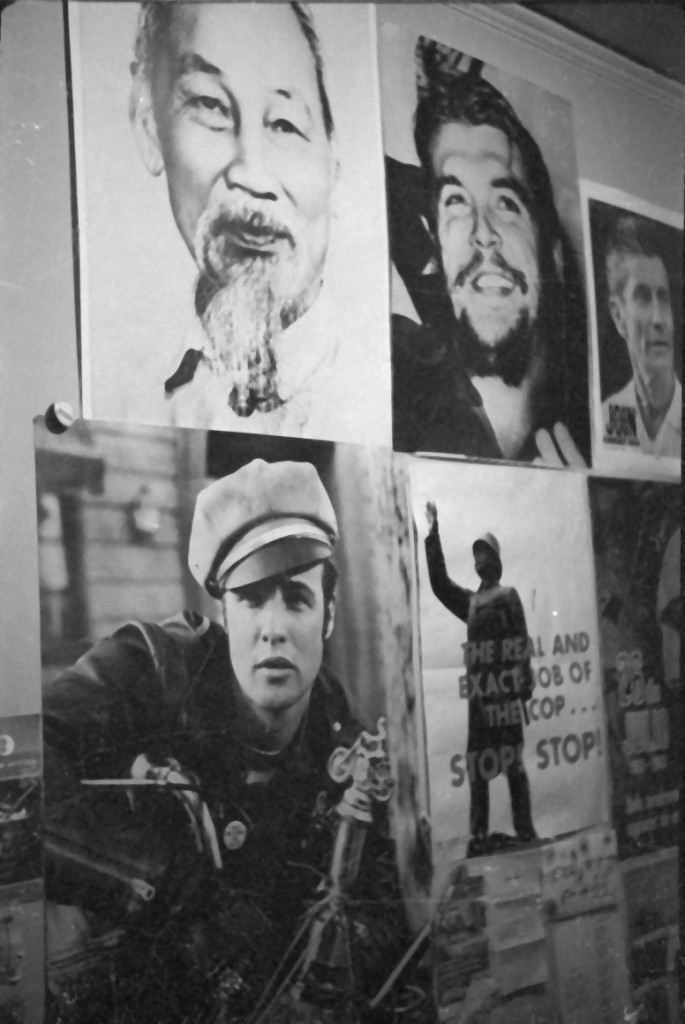

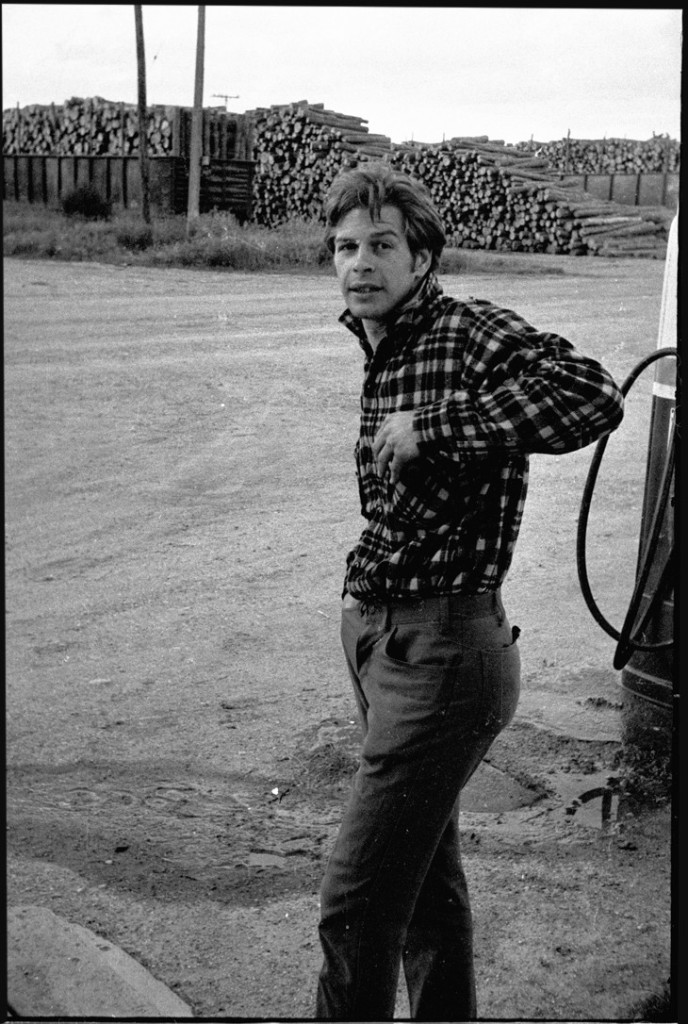

Posters on the wall above my desk. Uptown Chicago, 1967. Photos by Michael James from his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.

[In this series, Michael James is sharing images from his rich past, accompanied by reflections about — and inspired by — those images. This photo will be included in his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.]

The summer of 1967 was hot — real hot. Temperatures soared and so did social unrest. Air conditioners were scarce and so was any semblance of authentic legislation to alleviate poverty and its co-conspirators, repression and neglect.

On the worst of the hot days I would go in DeMars restaurant in Uptown, order a strawberry ice cream sundae, black coffee, and ice water, and sit in an air-conditioned turquoise booth that gave me a view of the intersection of Wilson and Sheridan. Nights were the worst. I attempted sleep after a cold shower, lying naked on the bed with a fan blowing over me.

Pictures from the Long Haul

My friend and fellow JOIN Community Union organizer Bob Lawson and I spent time hanging out in a bar on the northeast corner of Wilson and Clifton. The northwest corner had recently been leveled and Lawson handed Mayor Daley, there to kick-off construction of a new firehouse, a copy of JOIN’s The Firing Line decrying “poor people removal,” our term for so-called “urban renewal.”

1967 was the long hot summer of urban uprisings, and we thought that bar, a combination hillbilly/old guys drinking den, was the perfect spot to catch any street action. Revolt broke out in over 150 U.S. cities, including Chicago. Our idea was to encourage young southern white guys to join the blacks if anything broke out in Uptown or elsewhere in Chicago.

We heard that during the Detroit rebellion one in 10 of the arrestees was white; they were rebelling against oppressive conditions along with blacks. A black woman was quoted in the Chicago Sun-Times saying, “ This wasn’t no Negro riot — it was an all-of-‘em riot.” We believed poor whites could side with blacks and not against them. We heard that in Providence, Rhode Island, a black uprising was followed by whites attacking blacks as they yelled, “White Power!”

Bob and I wrote an article for the August 1967 issue of The Movement, an organizer’s paper originally published by Friends of the Student Nonniolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in San Francisco. “Poor White Response to Black Rebellion” attempted to address the question, “How will poor whites respond to black rebellion?” We said we weren’t sure, but did know that many poor whites in Uptown understood their situation wasn’t so different from that of many blacks; both suffered at the hands of the “big guys” like slum landlords and the police.

While awaiting the class struggle on the corner, we immersed ourselves in the country tunes that blared from the bar’s jukebox, rife with tales of wrongdoing, abuse of the working man, and love gone wrong. That was the summer I fell in love with George Jones, especially “Take Me.” That song brought back memories of my recent times in California.

I moved from my basement apartment on Hazel into a third-floor crib at Sunnyside and Magnolia, street names seemingly plucked from a country tune. My college pal Patrick Sturgis, aka Patrix or just Trix, was my roommate. The wall along the entryway where I had a desk (made from a door) was covered with posters, including pictures of Marlon Brando, Ho Chi Minh, and Che Guevara, all guys I looked up to.

Another poster on the wall pictured the statue erected to honor the police “heroes” from the Haymarket rebellion with the caption, “The real and exact job of the cop: Stop! Stop! Stop!” Years later the Weathermen blew that statue off its base and today it resides inside Chicago Police headquarters, protected from the people.

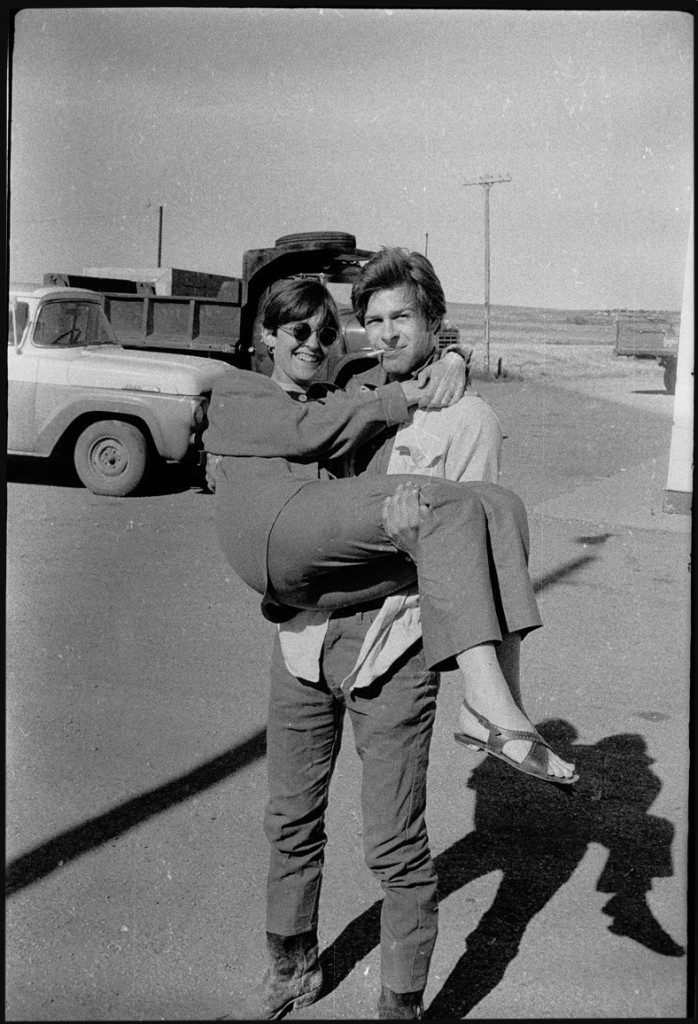

My ex-squeeze from high school days, Susan Lum, came to Chicago to work in the National Office of SDS. She and Patrix were going out. One night around midnight the three of us got stoned and decided to head West in my old VW, the “Appaloosa Mother.” We rolled through the Rosebud Sioux Reservation and as far west as Buffalo Gap, South Dakota.

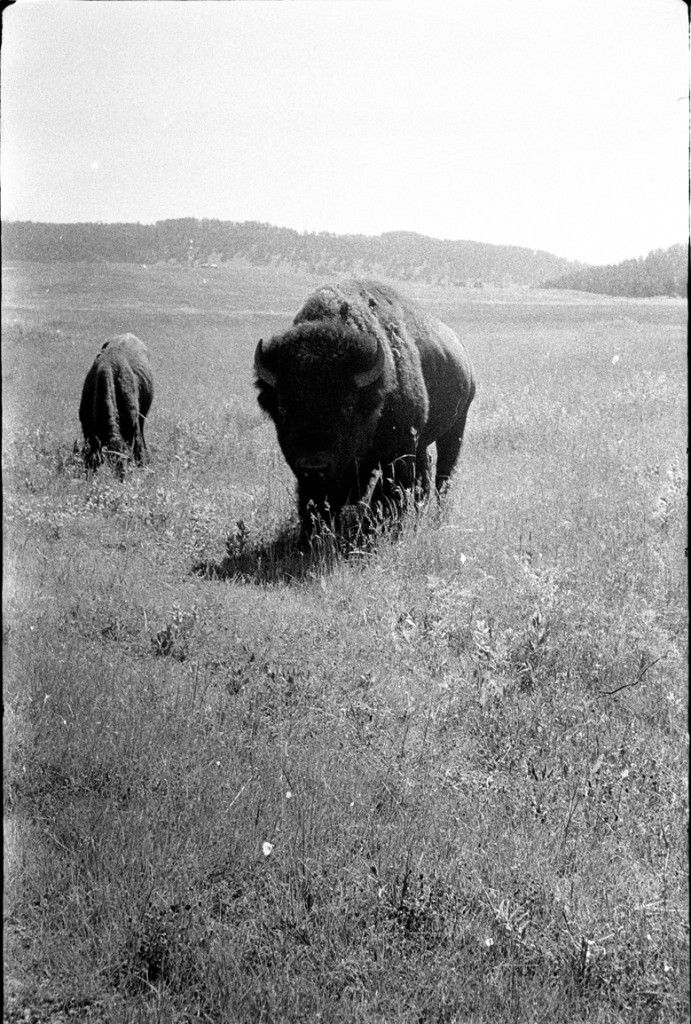

In Winner, South Dakota, the owner of a trading post showed me a maggot-covered buffalo skull he was curing out back. Riding west on a rutted dirt road we waved at some Indian kids who responded with a middle finger. Later that day we came upon my first non-zoo buffalo. We frolicked around a stock tank and climbed up the windmill. We left when a large herd of cattle appeared on the horizon, headed our way.

When it was dark we pulled into Wind Cave National Park. We’d bought a chicken, rubbed it with freshly harvested sage, and were about to cook it up when two Park Rangers arrived, flashlights and guns drawn. We had to follow them to their office, where they did some paper work and fined us for illegal camping and starting a fire.

We told them we were broke and were permitted to just sign our names, after promising we’d send in the money when we got back to Chicago. The Rangers guided us to an official camping spot where we finally cooked the sage chicken in a legal space.

The next day we stopped along the road on a small bridge over a dried-up river and shot 8 mm footage — now long disappeared — featuring a woman tied to a train track being rescued by a noble cowboy. Patrix played the hero and, against type, I played the bad guy. Patrix saved Susan, a perfect role since the two of them were giddy with love.

Later that day we walked into a bar at a crossroads called Buffalo Gap. I’ve never been sure if we were shunned, avoided, or overlooked, but we were totally ignored and so left to explore. We took in the main street, which sported an abandoned hotel and timber-filled rail cars sitting on a track.

Then we headed up to North Dakota, stopping en route to take in an old cemetery, have lunch, and have the car repaired in Bismarck. But we all had obligations in Chicago centered on making the next American Revolution, so after four days on the plains we turned around and came back. When we arrived home I returned the spare tire I had borrowed — without permission — from Marilyn Katz, who was pissed.

Back in the “guts of the ogre” we recruited and trained more people to organize for change. Rennie Davis established a school to train community organizers. The first session there was run with assistance from folks from LADO (Latin American Defense Organization). We shared lots of stories and techniques developed by JOIN Community Union’s internal school.

Peggy Terry, the Southern mom living on welfare in Uptown and editor of The Firing Line, talked to the group about organizing and putting out a community paper. By the fall of 1968 I was managing her campaign for Vice President of The United States.

In March 1968, I joined Joe Blum and Terry Cannon (of the The Movement newspaper) on a road trip. We started in San Francisco and headed south, visiting organizers and projects along the way. When we got to Los Angeles I met Mike Klonsky at the SDS office, and he became a lifelong friend.

We stopped in Silver City, New Mexico, and visited a union hall. Silver City was the site of a great labor film — Salt of the Earth — about a strike by the United Mine Workers in the 1950’s in which women played a major role. In New Orleans we did a little drinking with renowned power-structure researcher Jack Minnis and organizer Mendy Samstein, who both worked with SNCC.

We hadn’t let people know ahead of time that we intended to visit, which on two occasions proved a little awkward. In Hattiesburg, Mississippi, we stopped at the home of Fannie Lou Hamer, the legendary leader of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which in 1964 had challenged the regular Democratic delegation and the entire Democratic Convention over equality and representation.

Mrs. Hamer was in her backyard doing laundry in a kettle over an open fire. This inspirational woman was polite, but clearly not too excited about having three white dudes show up unannounced at her home.

And in Nashville we found SNCC workers who quite rightfully were initially cautious about us showing up out of nowhere. On the way back to Chicago we stopped and rested up in Cincinnati, where we stayed at Terry’s parents home and enjoyed good food and a stimulating conversation about Mormon Church history. The Cannons were descendents of the Church’s founder.

Things moved fast in 1968. On the JOIN front, Peggy Terry and the young guys had gone for autonomy and control of JOIN, partially as the result of being encouraged to do so by Tom Mosher (who turned out to be a police agent provocateur). This move, along with the changing political climate and new opportunities for other work in organizing for social change, led many of the students who had worked with JOIN to leave.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. King was gunned down in Memphis. I headed to the SDS office on the 1600 block of West Madison and watched from the window as people tore apart and gutted a Woolworth’s store. Not long after, on June 5, Bobby Kennedy was killed.

The War in Vietnam raged on, dividing the nation and much of the world.

The War in Vietnam raged on, dividing the nation and much of the world. A group of organizers, including Slim Coleman, called for community-based organizing against the draft. I wrote a piece for The Movement, signed by a number of JOIN organizers, critical of that direction. In it I claimed such work would undermine and disrupt the slow, steady, long-range community organizing we were engaged in. History proved me wrong. But all that changed anyway when the 1968 Democratic Convention came to town.

The War was the dominant issue of the day by the summer of ‘68, even more than race and poverty, and I stood corrected about organizing the community around it. Patrix and I designed a poster with a picture of a mean-looking cop in sunglasses (who as it turned out was actually a motorcycle film courier). It said, “Hot Town! Pigs in the Streets! But the Streets Belong to the People! Dig it?” I signed it “Sunshine Jubilee.”

The story of that poster was told many years later when the sociologist Tukufu Zuberi, of PBS’s History Detective, interviewed me for an episode of the show. His investigation centered on finding out who or what was “Sunshine Jubilee.” When he tracked me down and asked me, I responded “Me.” Sunshine Jubilee was my nome de design back in the day.

I also told him my only regret was putting that question mark rather than an explanation mark after the Dig It! I really liked Tukufu, including his background: he ran track at San Jose State and attended the Black Panther Party’s Breakfast for Children program when he was growing up in Oakland.

Back to summer of ’68: when the Democratic Convention came to town I was all in, though of course I could never have known how it would all explode, nor the impact of this event. In Lincoln Park, near the Farm in the Zoo, we were laying on the berm east of Cannon Drive listening to the MC5 and White Panther leader John Sinclair when the pigs came in to clear the park. They wore gas masks and fired many loads of tear gas toward the crowd.

That started it, big time! We responded with action in the streets. On Michigan Avenue the police prevented us from marching to Dick Gregory’s home. At night we went to the Armory up on Broadway, and talked to members of the National Guard. On Wednesday the 28th of July we were demonstrating at Michigan and Balbo when a police squadrol careened into the intersection, barely missing demonstrators.

Patrix and I were photographed, along with Warren Lemming, Nate Herman, and others, rocking that paddy wagon, trying to tip it over. Over the many years since then it’s been reported we turned it over, but in fact we didn’t succeed.

Printed and distributed widely, that picture has brought me considerable attention over the years. What the photo does not capture is the moment when I took down the cop who came out the driver’s door and jumped one of the squadrol rockers. I’ve been told that one of the many interviews I did about that incident was for a time shown to police academy trainees. But when it happened in the fall of ‘68, that picture led to my arrest on a John Doe warrant.

After that tumultuous convention many SDS people gathered at Sander’s farm near Valparaiso, Indiana. I met Betty and Dave Sander through Dave’s brother Joe Sander, who lived in Uptown and was on the board of the local War on Poverty. Joe was progressive and became an ally. Many years later, I spent time with him while he sat writing in the Heartland Café.

At the 1968 meeting out on the farm we discussed the approaching election. California’s Peace and Freedom Party wanted SDS President Carl Oglesby to run for VP on their ticket, with Eldridge Cleaver for President. SDS people wanted no part of it. With Oglesby out, Peggy Terry became the candidate and I became her campaign manager. We intended to use the campaign to raise consciousness and to meet and train organizers throughout the Midwest as a complement to the work JOIN was doing in Uptown.

Peggy didn’t win the election. However, our merry band of organizers toured the Midwest and showed up at political events in California. We made contacts, honed our organizing skills, and had adventures.

One of the most memorable of these adventures took place at a rally in a Kroger parking lot in Louisville. We were working with Carl and Anne Braden of the Southern Conference Educational Fund. Peggy and I were leading the crowd singing “We Shall Overcome” when suddenly the police disappeared and a large group of Ku Klux Klan members emerged, throwing rocks and attacking the crowd.

After the 1968 election Bob Lawson and Diane Fager began organizing in Cincinnati. Along with Steve Tappis, who worked at the SDS National Office, I moved into a storefront at Armitage and Kedzie. The welfare women continued to organize. Peggy’s son Doug Youngblood, Hi Thurman, Junebug, and others began the short-lived Young Patriots Organization.

And I along with Tappis, Patrix, Stormy Brown, Mary Wozniak, Peter Kuttner, Jimmy Cartier, and Lisa McInroy, started the newspaper and organization Rising Up Angry, geared to capture the interest and imagination of white working class kids in Chicago and beyond.

Find more articles by Michael James on The Rag Blog.

[Michael James is a former SDS national officer, the founder of Rising Up Angry, co-founder of Chicago’s Heartland Café (1976 and still going), and co-host of the Saturday morning (9-10 a.m. CDT) Live from the Heartland radio show, here and on YouTube. He is reachable by one and all at michael@heartlandcafe.com. ]

Every time a new post comes out I stop what I’m doing and make it a priority to read immediately.

I am so enjoying this whole series. Having gotten into writing my own reminiscences, I find yours so much more interesting.

That’s encouraging that poor whites joined with blacks in the Detroit riots, the two groups have so much in common. Sad that the former has moved to the right.