I was in a phase of life when I was trying to integrate radical politics, spirituality, and personal growth and development.

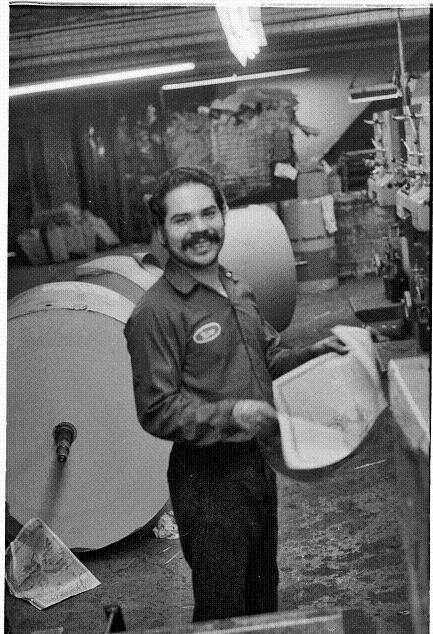

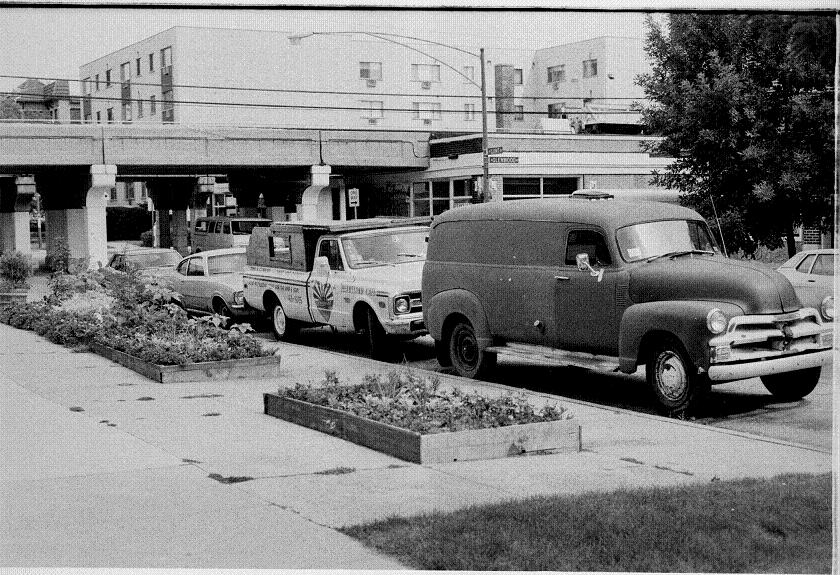

Heartland Journal comes off the presses at Newsweb, Chicago, 1984. Photos by Michael James from his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.

[In this series, Michael James is sharing images from his rich past, accompanied by reflections about — and inspired by — those images. These photos will be included in his forthcoming book, Michael Gaylord James’ Pictures from the Long Haul.]

I love the motto “educate to liberate” and am no wallflower when it comes to sharing my opinions, especially on political issues and current events. Through the ’60s and ’70s I was involved in spreading the word by working on and starting several publications, notably Rising Up Angry from 1969-1975. And not so long after opening the Heartland Café in 1976 I began to feel the urge to return to the presses. Thus in 1979 I was back at it, and began publishing The Heartland Journal: A Free American Journal of Heath, Sport, Culture and Change.

This time around I created a journal that featured things I was interested in, including issues and topics I knew were important but wanted to know more about. I was in a phase of life when I was trying to integrate radical politics, spirituality, and personal growth and development.

Pictures from the Long Haul

I used the term “comprehensive consciousness,” by which I meant a meta-awareness of the multitude of things that influence us. I also talked about “cosmic consciousness,” a popular concept of the day which probably meant comprehensive consciousness coupled with some kind altered consciousness plus spiritual influence from the great unknown — whatever that would be.

Essentially I wanted a paper that helped encourage, influence, shape, and develop a positive and forward-looking awareness of the world.

Books, magazines, newspapers, and flyers had always been an important part of my life. I loved looking at the pictures and captions in Life, Look, and National Geographic, publications we had in my family home in Connecticut. In the 1950s I devoured each issue of Hot Rod Magazine and Sports Illustrated.

On Sundays after the service at Saugatuck Congregational Church we picked up the Sunday New York Times at Bill’s Smoke Shop and went home for waffles with Vermont maple syrup and bacon. I would comb the Times‘ sports section and look at the ads in back of the paper for cameras and mukluks — “cool” leather and canvas boots allegedly great in the snow. During the summer of 1963 I spent time at the Westport Public Library, where I read The New York Times cover to cover and Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving and Marx’s Concept of Man.

I didn’t ever deliver papers, but during my high school years I did have a job putting them together, collating sections of the NYT beginning at 5:30 am at Bill’s Smoke, a newsstand, tobacco, and snack shop owned by the family of fellow Downshifter Hot Rod Club member Don Bulkitis. Before getting that job I had once stolen a girlie magazine from Bill’s magazine rack; I learned an important lesson when an employee spotted me and took me aside for a serious and meaningful conversation on theft.

Selling periodicals began during my stint as a ‘Tenderfoot’ in the Boy Scouts.

The first time I cranked out flyers and information, albeit not political, was at Bedford Elementary School, where I had the responsibility of running a purple-ink ditto machine. Selling periodicals began during my stint as a “Tenderfoot” in the Boy Scouts, when I sold popular magazines to neighbors and the parents of friends. I won a trophy for selling the most magazines and made a few bucks. (Not long afterwards, I resigned from the Scouts over what I perceived to be favoritism shown by the troop leader to his son over the rest of us Scouts.)

Little did I know then that writing for and hawking papers, gathering articles, selling advertising, and then selling and distributing newspapers, would become an ongoing part of my life.

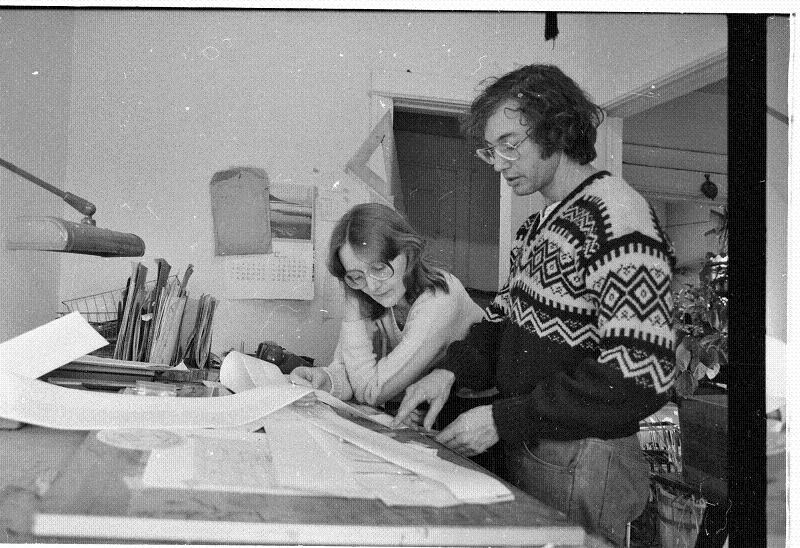

Lester Doré and Diane Scott, working on an early edition of The Heartland Journal, Chicago, circa 1980.

At Staples High School, I wrote sophomoric articles for the school paper Inklings, in which I celebrated hot-rodders who built their own cars and criticized kids whose dads bought them sporty new rides. My first paying job for writing and photos came when I reported on drag racing and car shows around New England for Drag News and Rodding and Restyling Magazine. At Lake Forest College I wrote articles and editorials for The Stentor in which I criticized the Greek system and any powers that be.

I had the real pleasure of working with Peggy Terry to start ‘The Firing Line.’

While a community organizer in Chicago’s Uptown from 1966 to 1968, I had the real pleasure of working with Peggy Terry to start The Firing Line. During that time I also wrote a column for the SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) organizers’ paper The Movement, as well as articles and reporting for the radical weekly The Guardian, the Chicago Seed, and Bill Knight’s Prairie Sun out of Macomb, Illinois. In July of 1969 I began Rising Up Angry, the publishing arm of the radical community organization by the same name that came out every three weeks from 1969 to 1975.

Around the time of the 1968 Democratic Convention I conceived and produced my best propaganda poster: “Hot Town, Pigs in the Streets, but the Streets Belong to the People: Dig It”—that many years later would be featured on PBS’s History Detective.

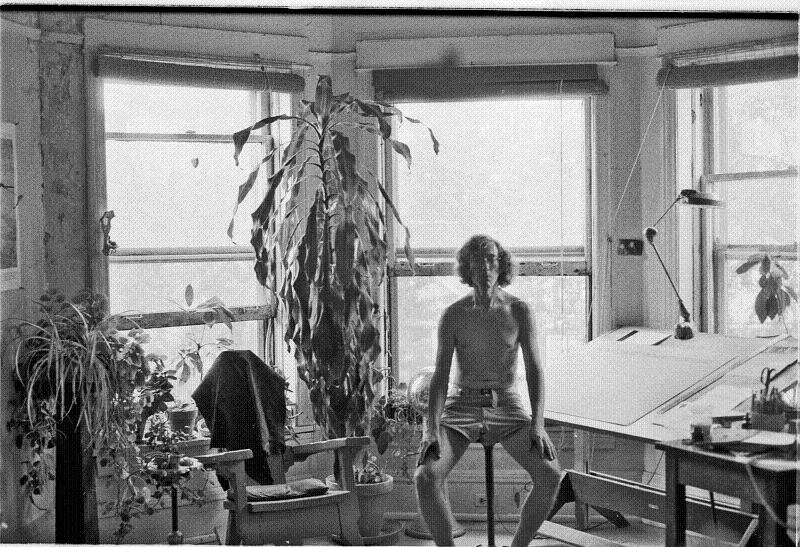

When starting RUA I met the graphic artist Lester Doré at The Seed and asked him to design the new logo and masthead for RUA. Lester is from the Tabascoland of New Iberia, Louisiana, by way of Tulsa, Oklahoma. He came to Chicago to seek adventure and study art. He did beautiful work for The Seed, for Skeets Millard’s Kaleidoscope, and for The San Francisco Oracle. Lester designed the iconic graphic of a marijuana leaf overlaying a peace symbol, a symbol of the 1960’s.

So after two years of being in business with the new Heartland Café and I got the urge to publish again, Lester was the guy I went to, turning what began as the small Heartland Newsletter into the attractive and comprehensive Heartland Journal. From 1979 to 2005, with the help of a series of gifted editors, we shaped and produced 52 issues of our paper, “A Free American Journal of Health, Sport, Culture and Change.”

The first cover was of a rising sun wearing sunglasses coming up over Chicago and

the countryside beyond.

In the spring of ’79 we collected articles for publication. Diane Scott, a former student in my “Organizing for Social Change” class at Columbia College, did the typesetting. In my apartment on Greenview, (aka my third floor “castle in the sky”), we laid out the paper, which back then involved a process of adhering graphics, headlines, and typeset articles via hot wax to the layout sheets covered with a light blue grid. The first cover — by the multi-talented maintenance man at Columbia College, Larry David Dunn — was of a rising sun wearing sunglasses coming up over Chicago and the countryside beyond, the type proclaiming: “Here Comes the Sun.”

The first Heartland Journal included articles critical of McDonald’s and Nestle. On the death and remembrance front, we bade farewell to civil rights pioneer A. Philip Randolph (called “the Most Dangerous Negro”); to Stony Robinson, who had the featured role in Andy Davis’ film Stony Island; and to the late jazz great Charles Mingus.

We remembered the assassination of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton by the Chicago Police Department. The music section featured RUA comrade Mike McGraw and his Piranha Brothers band, and included a review of Bob Seger’s “Night Moves,” as well as Bill Knight’s overview on “Midwest Rock ‘n’ Roll.” The centerspread “glamour spot” focused on two paths toward a non-nuclear future. Other articles covered running, biking, Tai Chi, and former NFL player David Meggyesy sharing his reflections on “Mind and Body.”

I wrote my first of many publisher’s editorials. Eventually they were called “Buffalo Notes” and appeared in each issue. The first one, “Stand in the Sunshine,” called for “developing a Politics of Affirmation”:

…I think we need to develop and encourage this life-stance, politics and attitude of affirmation, this strengthening of the positives, stressing the good, beginning to acknowledge, understand and overcome our negatives, both on the individual and collective level. … The Heartland Journal comes from this direction. We are very simply about encouraging the improvement of the individual and collective in both behavior and activity. We want to contribute to an amazing transformation of industrial society and the planet as a whole, helping in our way to make it more humane, more creative, and full of experiences that move us all along that path to the place where we really can share one Heart.

This first ‘Heartland Journal’ was printed

in a friendly print shop up in

Port Washington, Wisconsin.

This first Heartland Journal was printed in a friendly print shop up in Port Washington, Wisconsin. (We arrived on the eve of its printing, and that’s where I first had and fell in love with smoked chubs, a fish from the Great Lakes fishery.) Subsequent issues were printed in Chicago at Fred Eychaner’s Newsweb, where the Chicago Reader was printed. We held Fred in high regard; he had printed both the Black Panther and Rising Up Angry a few years earlier, when very few newsprint presses were willing to print radical periodicals.

When the first issue of Heartland Journal came off the presses I hauled all 30,000 copies back to the Heartland Cafe in my newly acquired 1949 Chevy panel truck, which had earlier served as a milk truck in South Dakota. Back in the city, still freshly abuzz with the wonderful rush I got when a new issue of a paper comes off the presses, Issue No. One was distributed far and wide. “Wide” meant sending it out to family and friends as well as taking it with me and giving it out or leaving it wherever I went, locally and beyond.

Heartland trucks: I hauled 30,000 copies of the first Heartland Journal back from Port Washington, Wisconsin, in the old South Dakota milk truck, a one ton Chevy panel truck, and firewood in the Chevy pickup.

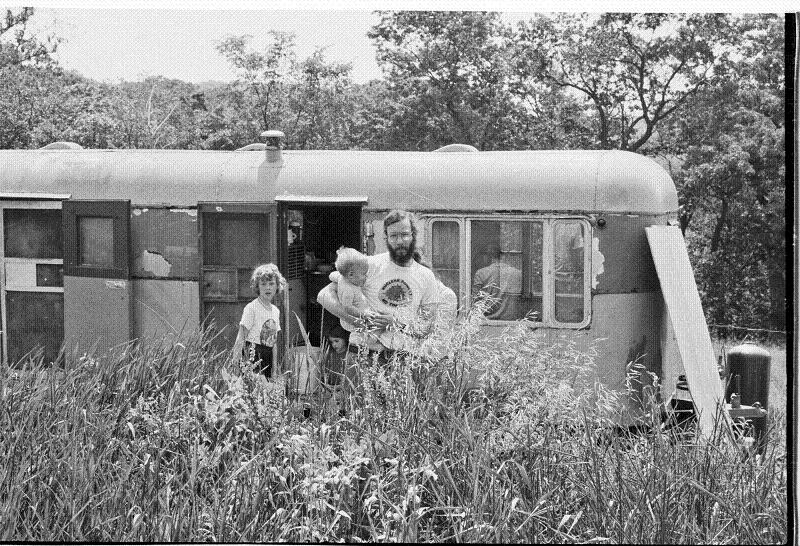

Lester had moved “back to the land” with his family, living in a beat-up trailer while building a semi-circular stone house in a field on the Karma Farm in New Lisbon, Wisconsin. I visited regularly and when The Heartland Journal began, a regular ritual evolved. Within a day or so post-printing I would drive Lester back to the farm. We dropped papers along the way and dropped hundreds in bundles at food coops in Madison, and always left a few with a young waitress who regularly served us coffee at a truck stop in Mauston.

Often, when returning Lester to his home, I incorporated other missions and activities. This included working a slab heap of one of Lester’s neighbors — cutting the outer slabs of harvested timber to firewood size before hauling it back in my pickup to the Heartland to feed our wood burning stove, the Radiant Darling. I took great pleasure cruising country roads, reveling in the streaming imagery of land, barns, houses, flora and fauna, livestock, vehicles, rusted tractors, and, now and then, people.

On Karma Farm there was a hippie industry called Inky Fingers.

On Karma Farm there was a hippie industry called Inky Fingers, a t-shirt printing operation located in an old barn. If and when the timing was right, I returned to Chicago with dozens of freshly silkscreened Heartland Cafe t-shirts for our Heartland General Store. I also replenished our supply of Lester’s line of Bird Lives jazz t-shirts, beautiful images of the likes of Miles, Monk, Mingus, Coltrane, Dolphy, Holiday, Parker, and — on the occasion of his performance at the Heartland — Native American sax player Jim Pepper.

On one occasion at the farm, Lester, our pal Dan McNeal, and I harvested some rabbits I had begun raising on my back porch in Uptown. We moved the rabbits to the Karma Farm and while rabbit fried in cornmeal batter tasted great, the butchering part didn’t sit well with us, leaving us with no desire to keep the project going.

These regular trips to Karma Farm gave me mental, physical, and spiritual nourishment, a respite from the glorious but intense and challenging urban life I led in Chicago. My time at the Farm reaffirmed my love and connection to the land, and kindled a sustaining flame when I returned to Chicago for more work, play, politics, and publication of The Heartland Journal. The Journal was integral to the mission: spreading the word on our beliefs, insights, visions, and hopes for the future — and of course, spreading the love.

Find more articles by Michael James on The Rag Blog.

[Michael James is a former SDS national officer, the founder of Rising Up Angry, co-founder of Chicago’s Heartland Café (1976 and still going), and co-host of the Saturday morning (9-10 a.m. CDT) Live from the Heartland radio show, here and on YouTube. He is reachable by one and all at michael@heartlandcafe.com.]