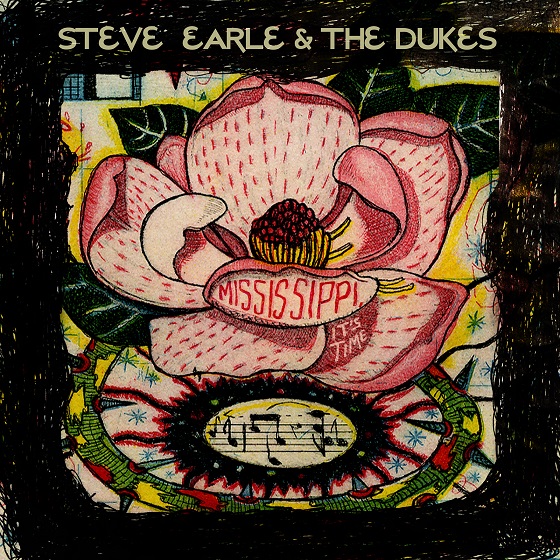

With this song, son-of-the-South Earle aims to help convince the Magnolia State to eradicate the Confederate symbol from its flag.

‘Mississippi: It’s Time‘ is Steve Earle’s passionate musical response to the Confederate flag controversy.

“It’s largely about empathy,” says Steve Earle of his mandate as a songwriter. “The job is about empathy whether you’re writing love songs or political songs.” The musician, author, actor, and activist’s newest song hit iTunes on September 11 and it clearly shows how empathy can be the prime motivation for the political. Entitled “Mississippi, It’s Time,” it’s his response to the Confederate flag controversy that flared following the church massacre of nine black Americans in Charleston, South Carolina, in June.

After photos of the serial killer brandishing said flag surfaced, both Alabama and South Carolina removed it from statehouse grounds. The last holdout is Mississippi which incorporates it in the design of their state flag. Son-of-the-South Earle is aiming to help convince the Magnolia State to eradicate the offensive symbol.

Michael spoke with Earle on the phone while he was on tour in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Speaking on the phone while on tour in Knoxville, Tennessee, Earle points out that what’s considered the Confederate Flag is not even indigenously from Mississippi. “It’s the Battle Jack of the Army of Northern Virginia,” Earle notes. “It has no history in Mississippi until the 1890s. And state flags did not exist until the Civil War. We were one country and we had one flag.” Through a bureaucratic error, the state went without an official flag from the early 1900s until 2001, when voters approved a measure legally restoring the so-called Confederate flag to Mississippi’s standard-bearer.

But dubious history is hardly its worst sin. “I don’t think that anyone can argue now that it no longer represents racism. Whatever you want to say about cultural heritage, that flag doesn’t represent anything but racism now — and it especially represents racism to black folks, which is reason enough for white folks not to ever fucking wear it. It’s disrespectful and a form of terrorism to subject them to it.”

Earle believes that sentimentality over the Confederacy is simply wrong. “I lived all of my life in the South until I was 50 years old and I don’t believe that Southern culture is the Civil War. I believe it’s the least of Southern culture. To me Southern culture is Faulkner and Tennessee Williams and the blues and jazz. To make the Civil War who we are as Southerners is a huge mistake.”

A native Texan, Earle turned 60 earlier this year and is old enough to remember Jim Crow, i.e. American apartheid. “Northeast Texas is definitely a Southern culture rather than a Southwestern culture. There’s black folks there and the movie theater was segregated when I grew up. My mother’s mother had a maid and she would take us to the movies and we had to sit in the balcony — black folks couldn’t sit on the [ground] floor. I remember the local restaurant being desegregated — they didn’t put up quite the fight that people did in Alabama and Tennessee, but it was definitely a change.”

‘I was raised to believe the Civil War was fought to preserve the union & that it was about slavery.’

Earle never doubted which side he was on. “I was not raised to believe that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights. I was led to believe that the Civil War was fought to preserve the union and that it was about slavery and that the South lost and that the right side won.”

Divisive racial rhetoric and symbolism have long been used as yet another device to keep working people from banding together to identify those who unfairly profit from their labor. “It’s important to remember that there are people who have a vested interest in folks believing that all the bad stuff is happening to them because of the other. It’s an old American thing — Donald Trump’s doing it right now. In hard times you can get people to respond by convincing that something foreign — something from the outside — is the reason for all their problems. White folks in the South have been told that about black folks from the South ever since Reconstruction.

“The people who were in power in the South before the Civil War were the same people who were in power after the war. The problem is that in addition to all the poor white people were all these [newly-freed] poor black folks and the only way to control this situation was to set them against each other. To me, that’s what this stuff’s about. It’s about economics — the most powerful people have a vested interest in fostering hate because it keeps working people neutralized.”

The genesis of the song began with South Carolina finally removing the flag from their statehouse in July. Soon afterwards, at his annual songwriting intensive called Camp Copperhead, Earle began sharing the evolving composition with his students. “It was banging around my head and I put it up on a screen so the class could see me write the song. I rehearsed it in sound checks with my band and in Chicago we booked a studio and went in and recorded it. I contacted Southern Poverty Law Center and we were off to the races.”

It incorporates lyrical and musical references to the work of Nina Simone and Jesse Winchester.

The whole process took two months. Driven by Earle’s hard-strummed mandolin, the song incorporates lyrical and musical references to the work of Nina Simone and Jesse Winchester, as well as the American standard “Dixie” — a revealing encapsulation of his eclecticism.

Profits from the song’s sales go to the SPLC, the venerable civil rights group. “They’ve been watching the Klan for us for a long time. I chose to give the money to someone because I wanted to make sure no one confused this with fiscal opportunism,” he laughs. A longtime anti-death penalty activist, Earle worked with the SPLC on that ongoing campaign.

“That’s a racial issue in the South whether anyone wants to admit it or not — and it always has been.” Earle remains optimistic. “I know for a fact that music changes things. At least four — maybe five times — I’ve had people come up to me and say ‘I changed my mind about the death penalty because of a song you wrote.’ All I can hope to do is to change one person’s mind — it’s literally one heart, one person, one pair of ears at a time. That’s not nothing — that’s how change happens.”

Find more articles by Michael Simmons on The Rag Blog.

[As leader of the band Slewfoot, Michael Simmons was dubbed “The Father Of Country Punk” by Creem magazine in the 1970s. He was an editor at the National Lampoon in the ’80s where he wrote the popular column “Drinking Tips And Other War Stories.” He won a Los Angeles Press Club Award in the ’90s for investigative journalism and has written for MOJO, LA Weekly, Rolling Stone, Penthouse, High Times, the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, CounterPunch, and The Progressive. Michael can be reached at guydebord@sbcglobal.net.]