A Conversation With Graham Nash:

Vietnam, Diane Arbus, and Green Day

By Mr. Fish / April 6, 2010

“They got guns, we got guns, all God’s chillun got guns!”

So sang the Marx Brothers during the frenzied buildup to the ridiculous war that finally erupted at the end of the 1933 anarchic comedy, “Duck Soup.” What has always struck me about that film, beyond its satirical strengths and punchy one-liners, was the fact that it was released during the worst year of the Great Depression, after the GNP had fallen a record 13.4 percent and unemployment had risen to 23.6 percent.

It was as if Hollywood were attempting to provide the public with a much needed escape from the agony of the massive financial crisis by allowing them the chance to remember, with some fondness, how preferable war, even a farcical one, was to staring the economic calamity clear in the face. If only a plunging dollar could be bayoneted and ballooning interest rates could be strafed out of existence; to have a mortal enemy to kill is always preferable to having a wound, stabbed into the back and out of reach, that bleeds the strength out of one’s optimism.

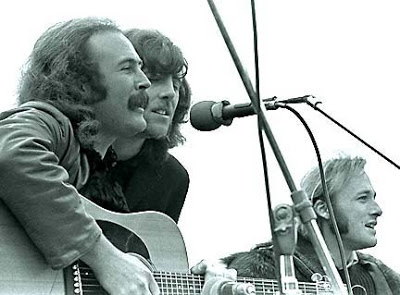

I’d gone to Atlantic City in August of 2009 to see Crosby, Stills and Nash to be reminded of the exquisite outrage that they, along with Neil Young, had so famously hurled into the hellish maelstrom that was the Vietnam War and to reapply its relevance to my own opposition to the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, desperate to forget how poor I was becoming, how many bills I’d be unable to pay at the end of the month, and how the current financial crisis, like the one almost 80 years earlier, was slowly dimming the lights on every other calamity in the world and making American self-pity the only agony worth woeing over.

Atlantic City in August, while indeed funky — and no stranger to brown acid or vast amounts of illicit sex between strangers — is no Yasgur’s Farm. Sure it is thrilling to approach by air-conditioned car, this metropolis of magnificent lights, skyscraper hotels, insomnia made jubilant by a gazillion flashing light bulbs, all of it pressed right up against the black ocean, but outside of the car it is abscessed New Jersey, the air damp and over-inhaled and brackish, smelling like a drunk octopus riding a horse through stale popcorn.

And then you enter any one of the casinos and immediately find yourself surrounded by the repulsive yin to the outside yang. Thusly, walking into the Borgata Hotel Casino for the CSN show, I found the air to be overly polite, like it had been blown through an Easter basket. And then there was the geometrically cacophonous carpeting as convincing of elegance and luxury as a 300,000-square-foot toupee; Tourette’s woven into a nauseating aesthetic.

And then there were the cheap sonsabitches walking around in loud shirts and crisp white sneakers trying to buy a million dollars with pocket change, their telepathy horse-trading so hard with Jesus Christ that their lips were moving.

With incontinent classical muzak dribbled through the PA system and making me feel more like I was waiting for a teeth cleaning than a mind blowing, I sat down in my assigned seat and, looking at the empty stage before me and the great hive of drums hanging amid a ridiculous contraption of chrome scaffolding and the fake candles wicked with four-volt bulbs placed here and there and the Flying V resting on a guitar stand, I began to worry that the men who I’d come to see might no longer exist; at best, like the candles, they might be poor parodies of themselves, having become so waterlogged by their own celebrity over time that the only thing left linking them to the glory of their past was the names on their drivers licenses.

I had to wonder if I’d made a huge mistake believing that, given the adoration of enough fans, an alligator bag might learn how to swim gracefully again; or that Muhammad Ali might be able to stop shaking just long enough to snatch a fly out of the air and be beautiful again; or that it could be 1969 again.

Then the lights went down. Then the trio of legendary sexagenarians took the stage, Stills in pleated black dress pants, Nash in bare feet and Crosby in an outfit one might throw on to clean out the garage. (Uh-oh.) Then the familiar harmonies were blended. Then, almost immediately, a mood as perfect as a pearl was fashioned right in the middle of all that superfluous and muculent funk surrounding us all.

It was breathtaking.

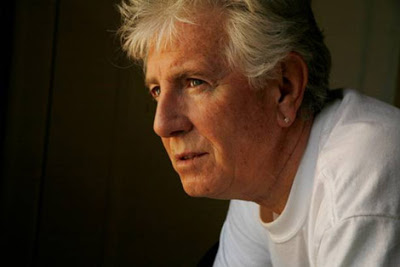

Five months later I found myself sitting down with Graham Nash at the Waldorf Astoria in New York to talk about both his recent induction, as a Hollie, into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the publication of his new book of photography, Taking Aim, a collection of candid photographs of musicians, past and present, some taken by Nash himself, all of them chosen by him, his commentary captioned on nearly every page.

Predictably, when you have a conversation with somebody as dynamic as Nash it’s easy to ping-pong wildly off topic, which we did. Despite being almost 70, up close his eyes appeared to be brand new and curious about everything. Typically closed when he sings, and he’s been singing for a long time, it made sense to assume that his eyes have probably seen less, though contemplated more, than the average person and, like coins with limited exposure to the outside elements, are now bright and shiny enough to practically emanate their own light.

Mr. Fish: Let me start things off with a quote by photographer Robert Frank: “When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of poetry twice.” I mention that quote because I think it expresses what is uniquely special about how you seem to approach both your photography and your music, which is with a great respect for the vulnerability of a particular moment.

Graham Nash: It’s all about communication. It has to communicate — that’s all I want to do. I don’t want everybody to agree with me — if they don’t agree with me, that’s fine. I’m just trying to communicate, it’s that simple. And I don’t want to waste your time, because that’s all we’ve got. When you boil it all fucking down, it’s your family and time, that’s what you have and you deal with it however you want. If I’m fine and my wife is fine and my kids are fine, the rest is a fucking joke.

And I can play this game — life — I know how to do it. I’m old. I’m 68 years old, right, and I know how to do this and I don’t want to waste your time. Same thing happens with a song — I do not want to waste your time with a song. Why waste three minutes of a person’s life that they can’t get back by singing them a song that sucks and doesn’t say anything? Why show somebody a photograph that’s a picture of nothing?

M.F.: Right, and that’s precisely what I mean about your focus and the moments you capture — you do have this reverence for time as an incremental measure of a meaningful life. Your best work, like “Our House” and “Simple Man,” “Lady of the Island” and others, reminds us how precious, how sacred, simple experiences can be when they’re unguarded and stripped of pretense.

G.N.: Yes—that is what I try to do, and I can only try.

M.F.: And your photography reflects the same reverence.

G.N.: I think a still photograph has an amazing ability to move. Of course it doesn’t physically move, but it moves you. If I put an image in front of you I want you to be thinking, I want you to be getting angry, I want you to be getting sad, I want you to fucking react — I want you to wake up!

And if I’m writing a song like “Chicago,” I want you to be angry because when you bound and chain and fucking gag a man and call it a fair trial you’re fucked! This is America, for God’s sake. We have a Constitution. We have respect for humanity. I don’t give a shit what Bobby Seale was doing in that courtroom — you cannot bound him and chain him and gag him and call it a fair trial.

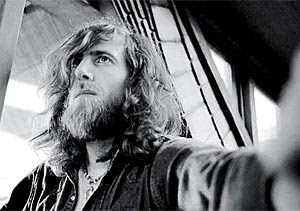

And when those kids got killed at Kent State, fucking Neil was furious and the way he dealt with his anger — same as you deal with your cartoons, you fucking pour it onto the page — we pour it onto the page of tape. And, again, we don’t want to waste your time.

M.F.: Which I think is what differentiates an artist from, say, a mainstream journalist or an anchor on the 7 o’clock news [who] want to waste our time and to pacify our anger and to keep us from dissenting against power. An artist’s main responsibility is to be honest and to not bullshit, which is contrary to the job of a politician or somebody whose objective is to preserve the status quo.

G.N.: Absolutely true.

M.F.: Now, just to illustrate what you said about the power of a good photograph, I read somewhere that your song, “Teach Your Children,” was inspired by your reaction to the Diane Arbus photograph, “Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park.”

G.N.: I’d actually written the song right before seeing the Diane Arbus, but when I saw that image… what had happened was I’d been collecting photography from 1969 onwards and in a particular show at the de Saisset Gallery in Santa Clara, which was the first show of images I’d collected, I put the “Hand Grenade” photograph next to a picture [by Arnold Newman] of [Arnold] Krupp, who was the German arms magnate whose company was probably responsible for millions of deaths.

It was an eerie photograph, a portrait, and the lighting is weird and his eyes are dark — a great image. And looking at them together I began to realize that what I’d just written [“Teach Your Children”] was actually true, that if we don’t start teaching our children a better way of dealing with each other we’re fucked and humanity itself is in great danger. I mean, look at what’s going on in the world today — look at the Obama administration. What a pile of shit we gave him to deal with, now he’s trying to deal with it all on many fronts and he’s getting shit for not concentrating on one thing.

M.F.: Well, frankly, I don’t think it’s the job of the president to solve many of the problems most threatening to us. I think it’s a mistake to think that the Office of the Presidency of the United States is a humanitarian position. Rather, [the presidency] is a job for somebody with a business mind — somebody who honors the traditional power structures and upholds the absolute authority of multinational corporations and who can manipulate information in such a way as to prevent regular people from noticing how little control they really have.

G.N.: And the dance between them all is insane.

M.F.: But let’s compare what’s going on in the world right now versus what was going on in the 1960s. There are some depressing similarities: We have an unjust and illegal war that we’re fighting — in fact, we have two, some would say more. All unnecessary and brutal and …

G.N.: Silly — yep.

M.F.: And, when you consider the economic crisis, you think of Dr. King and his commitment to helping the poor and lower working class.

G.N.: Sure, and the division between the rich and the poor is getting wider and wider and wider.

M.F.: And there’s the social unrest exploding all over the world in places like Greece and the Occupied Territories, Iran, and there’s the environmental movement still straining its efforts to save the species and now you have Obama talking about building new nuclear power plants, even after people like you fought so hard through the ’70s to stop construction, which was a remarkable victory.

G.N.: Right — when we did the No Nuke concerts at Madison Square Garden, there hasn’t been another nuclear power plant built in this country since.

M.F.: I know — it was such an incredible accomplishment.

G.N.: Well, when I met with Obama’s people, before I decided to support him, that was my first question: What is his stance on nuclear power? I knew about his relationship with Exelon in Chicago and I knew he got money from them, so I wanted to know what the hell his stance was. And they said, well, it’s a very interesting stance because he knows we might need it, but he knows we’ll never get it.

So he can afford to say that we need to do this, but he knows damn well that until we can figure out how to store the waste and until we figure out how to keep it out of the hands of terrorists, it’ll never get done. So I think he’s walking this brilliant line between appearing to support what is an unbelievable industry that has never made a penny and has taken billions from the American taxpayer and knowing that we’ll never get [new operational plants].

M.F.: But the message [Obama] is sending to the anti-nuclear activists, then, is that big business trumps their concerns. The pronouncement that we need to build more nuclear power plants can only be seen as the President turning his back on the left.

G.N.: I think they need to look a little deeper.

M.F.: I’m not so sure. I think the left would prefer a public victory to a private investigation into what may or may not be true about what a politician says.

G.N.: I think that’s right.

M.F.: I think that progressives would rather have an administration that honors their past victories and that doesn’t try to marginalize their deep concerns and send the message that the dominant culture is going to continue pushing liberal values aside.

Your point about Obama’s decision being a political move is not lost on me. However, I feel that I must point out my belief that perhaps the greatest contribution made by your generation was the idea that there should be no compromise on certain issues, particularly when it comes to things like war and pacifism and anything that threatens [to compromise] our humanitarianism or the public health.

In fact, I think that there is a lot of rage and disappointment coming from people who saw some of the liberal principles they believed [Obama] had but was forced to compromise to get elected as never having been part of his core belief system at all. I think that in the back of some people’s heads they thought he was going to be like Gandhi.

G.N.: Where is the disappointment coming from, though? What is he actually doing that is pissing the left off?

M.F.: Maybe it’s what he’s not doing that’s pissing them off.

G.N.: Like what?

M.F.: His amping up of the war in Afghanistan. His secret renditions program. The bank bailout. His position on gay marriage and Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. The nuclear issue we’ve been talking about. Support of Israel has been a sticking point, although some of the recent news on the illegality of the new settlements is pretty remarkable. The fact that you can all of a sudden criticize the Israeli government and not be called an anti-Semite is amazing.

G.N.: To have even put Israel in the middle of all that stuff is insane. Sometimes I wonder if we didn’t do it all deliberately.

M.F.: Right, like our supplying weapons to both Iran and Iraq during their war in the 1980s in order to help keep the region unstable and reliant upon our intervention for survival.

G.N.: Yeah, that’s right — Eisenhower was right, wasn’t he? But you have to add something else to what he said. It’s not only the military-industrial complex, but the military-industrial-commercial complex, because trying to make sure everybody is in line to buy a new pair of sneakers and a soda is insane.

M.F.: And that brings up another interesting comparison with the past. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, in order to be involved with the anti-war movement and in order to be an effective feminist and in order to fight for civil rights, you needed to do all those things in public. There was no Internet; there was no safety net that allowed you to privately involve yourself in a mass movement.

G.N.: Yeah, you had to do it publicly and there were risks.

M.F.: And that was even part of the appeal. I remember back to when I was seven years old in the early ’70s and how I wanted to grow up to be Angela Davis.

G.N.: Wow! How fantastic!

M.F.: And I really believed it was possible — I mean, why not?

G.N.: Yeah!

M.F.: And now I feel ripped off that I’m not Angela Davis.

G.N.: Well, when we had the opportunity to speak out, we did, even to the detriment to ourselves. But where is that movement now?

M.F.: I think the movement is being controlled.

G.N.: By whom?

M.F.: By the military-industrial-commercial complex. They don’t want us waking up. They just want sheep — go buy your sneakers, man!

G.N.: Exactly — and Old Navy can sell you a T-shirt with a peace sign on it and you can put it on and suddenly think you’re involved in the peace movement.

M.F.: And you don’t even have to do anything—just wear the T-shirt.

G.N.: Yeah, it’s insane. They learned with the Vietnam War, man, you know — when Walter was telling you every fucking night while you were eating your steak dinner how many fucking Americans had just been slaughtered. The public can only take that for a certain amount of time, then they start to write to their congressman, they start to get pissed and they start to rise up and then all of a sudden the Vietnam War stops. Right? Did you ever see any footage of Grenada? Did you see any footage of Panama? Did you see any footage of Iraq?

M.F.: No.

G.N.: They learned — they learned how to control it. And the media, as you well know — you can count on one hand who owns the media that covers the entire planet. They have no interest in people standing up and saying that the president doesn’t have any fucking clothes on.

M.F.: And what do you think can be done about that? Can the movement be revitalized? Is there a different strategy that people should be using…

G.N.: Sure, and here’s a perfect example. When Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, and I found out that Congress was trying to slip an odd sentence into an energy bill that would make the public responsible for $50 billion to restart the nuclear industry again we did a video of Stephen’s song, “For What it’s Worth,” with Ben Harper, with me and Bonnie and Jackson and we went to the Hill and met with all those people and showed them 126,000 signatures that we’d gotten in three days and we managed to get the sentence taken out.

I mean, we didn’t learn anything from Chernobyl? You know how many people are still fucked up from Three Mile Island? And you know it’s going to happen again. You can’t have 104 plants here and 72 in Japan and 15 in France and expect nothing to go wrong. In the ’50s they used to say that nuclear power would be so cheap that they wouldn’t even have to charge for it — bullshit! Do you know how much energy it takes to build a nuclear plant, to keep all that shit cool and safe so they can store it for thousands of years, the waste I mean?

We’re only 200 years old and we can’t control anything! How the fuck are we going to control this shit for thousands of years? It’s madness! It’s a industry that has no future — they’re only trying to make money on construction. They’re even trying to say it’s green!

M.F.: I guess radioactivity is green because you can’t see it — like it’s only theoretical pollution.

G.N.: Well, water is really the next big thing — there’s going to be wars over water. I knew this 33 years ago. That’s why I moved to the wettest spot on earth, I swear to God. I was in San Francisco and we were being told on billboards to shower with a friend because the drought was coming and stuff like that and I knew what we were doing to the Colorado River, how we were damning it and fucking it up, and all the San Francisco people were saying, “Why are we sending all our water down to that fucking desert?”

And I’m thinking, water, I’ve got to find a place where water will never be an issue. So 33 years ago I moved to Hawaii. Now I’m lucky enough to be able to do that, but that’s how serious I think the water problem is going to be.

M.F.: I think you’re right, and what scares me most is how we don’t currently have any kind of organized mass humanitarian movement that might help us survive such a catastrophe and prevent us from descending into real tribal savagery. I mean, one of the things that your generation had — that my generation doesn’t have — were young people who were able to articulate the politics of dissent and humanitarianism well and who were able to, for want of a better word, make progressiveness and radicalism sexy. That’s what drew people to the counter-culturalism of the time, the music, the fashions, the grooviness of it all …

G.N.: And we knew that, sure.

M.F.: You made it hip to thumb your nose at the Johnson and Nixon White House, but you also grounded [your dissent] in a certain logic — there was a great deal of sanity in wanting to stop the war and to argue against materialism and to live a more spiritual existence. It was more than just an opinion that you were pushing — it was a lifestyle.

G.N.: You’re absolutely right.

M.F.: And I just don’t see that happening nowadays. In fact, most unsettling to me about the recent death of Howard Zinn…

G.N.: What a brilliant man.

M.F.: Right, but what I found so odd about him dying was how unfair his passing seemed. I found myself wondering, “Wow, all the real radicals are disappearing.” It was like he was gunned down in his prime, but he was, what, almost 90? I suddenly realized that most of the people who make me want to be a bigmouth are all over 60, at least.

G.N.: [Progressive humanitarianism] moves forward in small increments. Did you see Pearl Jam on “Saturday Night Live” this past weekend?

M.F.: I didn’t.

G.N.: Right — Eddie Vedder, playing his guitar, and what’s written on his guitar? ZINN! And people can twist their heads up and say, “What’s that written on his guitar? Zinn? What the fuck is that?” And then they go to Google and they type in Zinn and all of a sudden they’re off!

M.F.: Right.

G.N.: I’m not saying that that’s the only way to do it — I’m just saying that that process is still going on. When you give a person too much to think about, they become inactive a lot. They get paralyzed. I mean, look at what kids are faced with today. I heard a thing on NPR the other day while driving around about how some of these medical students owe $300,000 in student loans. Think about that. How the fuck are they supposed to pay that back?

And the woman who they were interviewing said that she wanted to be a family doctor, but she couldn’t afford to be a family doctor. She has to subset and subset and subset and become the only doctor who does operations on ears and then she makes all the money, but it isn’t what she wants to do.

I want to be a pediatrician, I want to be a family doctor for people — you can’t! You can’t afford it! Lawyers are the same way. Accrue massive debt in law school and forget about going into something like civil law. You’re forced to becoming a lawyer for some corporation somewhere.

M.F.: It’s all very carefully designed. Keep the sheep occupied and we’ll rob them blind and they won’t even know. In fact, we’ll even smile at them and tell them they’re doing great — like you said, we’ll sell them a T-shirt and let them think they’re in the peace movement.

G.N.: Right.

M.F.: Keep everybody crazy.

G.N.: Another important lesson that came from the 1960s was the fact that it isn’t necessary to go to every march and to every demonstration and every sit-in and to be an expert on every bit of legislation that might be moving through Congress to be political. I think the notion that you require a vast understanding of every issue in public circulation can become a deterrent to people getting involved in dissent, like they’re not smart enough.

Again, that was the genius of [that] generation: it was enough for a person to remain committed to a lifestyle based on humanitarian ideals, to claim real ownership over his or her values and a lifetime dedicated to peace, love and understanding …

M.F.: Good ol’ Elvis!

G.N.: Right — and that was enough to be effective politically, because it was a way to exist off the grid and not rely so heavily on needing to be subservient to the dominant culture. In other words, so long as you don’t need laws to know that racism is wrong, or that sexism is wrong…

Or that homophobia is wrong …

M.F.: Or murder or stealing, yeah. As long as your ideas and beliefs are not determined by whatever rewards or punishments you feel you might receive from the state, you’re politicized and fighting power. You’re saying that your morality is self-generating and not imposed by an artificial hierarchy.

G.N.: Right, I’ll give you another example: We had my song, “Teach Your Children,” in the middle of 1970, bolting up the charts. …And then Kent State happened. We went down to Los Angeles and we recorded [Ohio], mixed it, recorded “Find the Cost of Freedom” for the B-side and we said we want it out right now. “Well, you can’t do that—you’ve got a hit moving up.”

We want it out right fucking now! We put that out in 12 days and the fucking cover for the 45 was a picture of the Constitution with four bullet holes in it. We killed our own single. You don’t do that — you’re not supposed to do that. We didn’t give a shit. We thought the slaughter of these four kids, which the government still hasn’t apologized for, was more important.

M.F.: And that’s what I’m saying, that that simple understanding doesn’t seem to be part of contemporary culture anymore, particularly when it comes to the arts community and the musicians who have historically been so effective in communicating that message.

G.N.: But they are there.

M.F.: Are they?

G.N.: What about the Beastie Boys? What about their Tibetan campaign? How about Green Day?

M.F.: Well, all right—Green Day is a good example.

G.N.: Let me tell you something—I have never met them, right? And as I was leaving the after party [for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony] at the Bull and Bear, in this hotel, I see Billy Joe [Armstrong] as I’m headed up the stairs and I don’t stop, you know, I just wave respectfully, and he parts the people around him and comes up and he hugs me for two minutes, babbling about what a great songwriter I am and how he wanted to be like me and write melodies that are in people’s hearts all the time and I said, “Wait a second—you have to understand, I am really proud of you.” Wait a minute, why’s that? “Because you’re doing what we did — you’re standing up there and fucking telling it like it is! “American Idiot” was brilliant!”

It kind of shocked him a little bit. But there is this chain of musicians who really do give a shit. They are there, maybe few and far between, but they are there. Tom Morello from Rage Against the Machine is a fucking brilliant man. And we’re trying to influence those people — me, people like James Taylor, we’re all trying to influence those musicians who are coming up and following us because we’re dropping off the other end of this diving board, we can’t help it. It’s called old age and eventually death. But we want to encourage people to stand up and to give a shit and to have courage.

[Dwayne Booth (Mr. Fish) is a renowned cartoonist and freelance writer whose work can most regularly be seen on Harpers.org and Truthdig.com. His website is Clowncrack.com. Dwayne Booth lives in Philadelphia, PA, with his wife and twin daughters.

Source / Truthdig

Thanks to Larry Piltz / The Rag Blog