The Triumph of Keynes: China’s Greatest Export

By Moshe Adler / November 14, 2008

Anyone who is wondering why Chairman Ben Bernanke and Secretary Henry Paulson favor fantastically expensive bailouts of private firms instead of Keynesian policies of direct governmental investments in the public sphere–and why the economics profession has by and large endorsed this approach — would do well to look back to the 2002 celebration of Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday. In his toast, Ben Bernanke, the future Chairman of the Board of the Federal Reserve, said to Friedman and Anna Schwarz, co-author with Friedman of the book ‘A Monetary History of the United States, 1863-1960,’ about the Great Depression: “You’re right; we [the Federal Reserve] did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

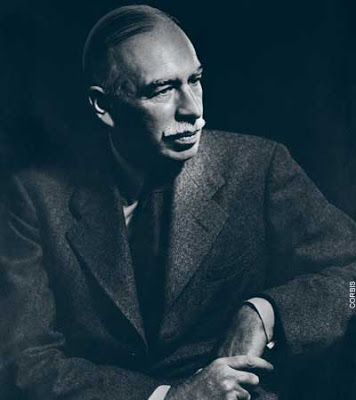

Why was Bernanke so eager to accept responsibility for a failure that occurred more than seventy years before he joined the Board? Because otherwise he and the economics profession in general would have had to concede John Maynard Keynes’ claim that a free market system is not self-regulating.

Of course, in 2002 it was entirely safe to assert that monetary expansion would have prevented the Great Depression. The Depression was long past and the Fed hadn’t taken the route that Friedman, many years later, asserted it should have. But now the country is teetering on the brink of economic disaster, and Bernanke, Friedman’s most devoted disciple, is at the helm of the Federal Reserve; push has come to shove. Either monetary policy alone can prevent the disaster, or the belief that the Free Market is self-regulating is dead.

Curiously, until Friedman brought it back to life, this belief in the Free Market was already dead. Intervention by the Federal Reserve did not use to be part of the definition of self-regulation. In fact, Free Market disciples used to argue that prices, not the Fed, were the mechanism that regulated the market. When the demands for goods and services fall, as they are bound to do when financial assets lose their value, prices fall. And this fall in prices would restore the economy to full employment, they argued. But this is not what happened during the Great Depression.

On October 29, 1929, Black Tuesday, the Dow Jones finished 23% below its level of five days earlier, on Black Thursday. And just as the Free Market disciples had predicted, this started a downward price spiral. Even thought the stock market crash happened at the end of the year, in 1929 prices fell by 2%. In 1930 they fell an additional 9%, in 1931 they fell 10%, and in 1932 they fell 5%. From 4% in 1929 it rose in the next three years to 9%, 16%, and 24% respectively. This is what led Keynes to conclude that unemployment was high not because prices were too high, but because consumers’ and investors’ optimism was too low. To operate at full throttle, Keynes explained, a Free Market system must be given one of two stimulants: Either a large dose of irrational optimism, or a high level of governmental demand for good and services.

The rate of unemployment in the years following WWII affirms Keynes’ view. The rate of unemployment was low (4.6% and below) during four periods, three of which involved irrational optimism, and one in which the government engaged in Keynesian policies. It was low in the 1950s when producers believed that consumers’ demand for home appliances, refrigerators, televisions, and vacuum cleaners, were insatiable. (Unemployment was high in 1954, however.) It was low at the end of the 1990s when the possibilities of the dot com world appeared limitless and people with stock portfolios felt like real millionaires. (At the time, President Clinton thought it made sense to invest some of social security funds in stocks.) And it was low in the years 2006 and 2007, an afterglow of the belief that home prices could only go up. The unemployment rate was most consistently low in the years 1965-1969, however, and this was due not to irrational optimism but to President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs. Over these years the federal government started channeling funds to primary and secondary schools and to universities, and a multitude of new government programs were created, including Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, Food Stamps, the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, PBS, and NPR.

The periods of irrational optimism inevitably ended when consumers and investors alike realized that there is no good for which the demand can grow forever, and that no new technology is revolutionary forever. The boost that the Great Society programs provided did not end, but it was no longer sufficient to keep the economy at full employment when at the end of the 1960s jobs in the private sector moved from cities to suburbs and from the Northeast to the South, leaving devastated cities behind.

But in 1967, when the memory of the Great Depression had substantially faded and no other financial meltdown was fresh in people’s minds, Friedman resurrected the argument that the Free Market was self-regulating. Lower prices would have restored the economy to full employment, he argued, if only wages declined sufficiently. Since we are now in the midst of a financial meltdown, it’s worth seeing what happens when Friedman’s argument is applied to today’s markets.

Between August 2007 and August 2008 home prices in the US declined 16%. The September to September numbers have not yet been published, but when they are they are likely to show an even steeper decline. Between September 2007 and September 2008 housing starts declined by 31%, and building permits, an indicator for how many projects are in the pipeline, declined by 38%. Over the same period (September to September) the employment of construction workers declined by 8%. Because of a statistical fluke which will be explained below, the data show that the wages of construction workers have increased by 9% over the same period. Let’s assume for a moment that the increase in wages is real. Following Friedman, do we then believe that if construction wages instead were to fall, housing starts would increase by 31% and building permits would increase by 38%’

The statistical fluke that shows that wages of construction workers increased when they are probably decreasing is this. The first construction workers to lose jobs when a recession starts are those who build small units, such as single family homes. Large projects are not as easy to stop. But workers on large projects are more likely than workers on small project to be union members and to possess high skills. Therefore, the recorded increase in the median wage of construction workers is most probably a reflection not of an increase in the wages of individual construction workers but of the disappearance of the lowest paid workers from the data. Whichever the case may be, it is clear that high wages are not the reason for the collapse of the housing market, nor would the housing market be restored if wages were lower.

The peculiar behavior of the median wage in the construction industry shows that in order to know how wages change over time it is necessary to follow individual workers, rather than industry-wide medians. The car industry was perhaps the most important industry before and during the Great Depression and fortunately there is data about wages, car prices, and employment in individual automobile factories during that time. These data show that when the price of the cars that a particular factory sold decreased, that factory employed fewer workers; the fact that in that factory wages fell by a higher percentage than car prices did, did not make a difference. And when the price of the cars that a particular factor produced rose, this factory employed more workers, notwithstanding the fact that in that factory wages rose faster than car prices did. (Author’s calculations based on the data of Timothy F. Bresnahan and Daniel M.G.Raff.) This would not have been a surprise to Keynes, who explained that falling prices squelch manufacturers’ optimism, and induce consumers to wait for even lower prices before they make their purchases.

But let’s return to Friedman’s argument. Let’s agree for the moment that had wages in the car industry or in any other industry during the Great Depression declined even more than they did, full employment would have been restored. Why didn’t wages fall sufficiently’ According to Friedman and to the economists Robert Lucas (also a Nobel Laureate) and Leonard Rapping — who jointly put Friedman’s argument into a formal model — wages did not decline even further because workers did not realize that the fall in demand that their own employers were experiencing afflicted also other employers. They were willing to quit their jobs instead of to accept lower wages because of the erroneous belief other employers would offer them higher wages. And this is why intervention by the Fed would have averted the Great Depression, according to Friedman. Had the Fed increased the money-supply sufficiently, prices in the economy, instead of falling, would have risen. That would have meant lower real wages for workers, and these lower wages would have restored the economy to full employment.

To economist Albert Rees the claim that the Great Depression was due to workers not realizing that there was a Great Depression was absurd: “How long does it take workers to revise their expectations of normal wages in light of the facts?” he asked. “Unemployment was never below 14 percent of the labor force between 1931 and 1939, and was still 17 percent of the labor force in 1939, a decade after the depression began.”

What all of this means is simple: Bernanke and the other policy-making economists are engaged in an ideological war that the rest of us simply cannot afford. We cannot afford to give hundreds of billions of dollars of government money to private firms and their executives just because their failure would expose the fact that a Free Market system is not self-regulating.

Free of an ideological commitment to the Free Market, the Chinese government has just announced a massive Keynesian program that involves spending on public housing, health, education, environmental protection, and transportation. The US should import this Keynsian prescription from China immediately. We should stop the giveaways while we still can and use the money to refurbish our society–while there is still the opening for making it great again.

[Moshe Adler is the director of Public Interest Economics, a consulting firm. He can be reached at ma82092@gmail.com.]

Source / CounterPunch