Historian Buhle writes about ‘The Irish socialist who organized an uprising’ and joins us on Rag Radio. (Listen to the podcast here!)

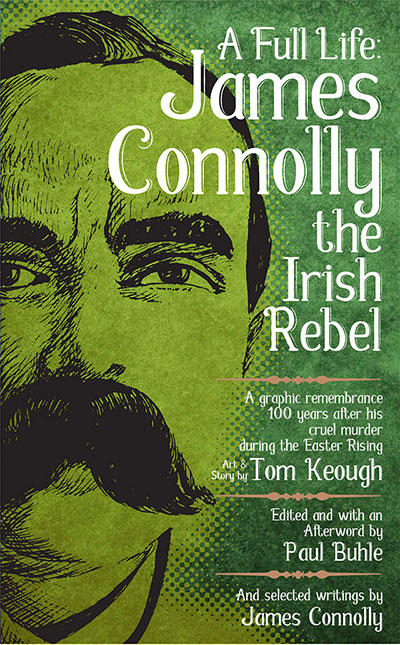

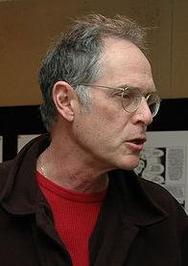

Historian Paul Buhle, a leading figure on the American Left since the 1960s who now produces radical comics, was our guest on Rag Radio, Friday, May 8. Buhle is the editor of A Full Life: James Connolly the Irish Rebel, subtitled, “A graphic remembrance 100 years after his cruel murder during the Easter Rising.” Paul also wrote an afterward to the comic which we are publishing below, along with Paul’s Truthout op-ed, “The Irish socialist who organized an uprising.”

On Rag Radio, Paul joined Thorne Dreyer in a discussion of the life of James Connolly, his role in the fight for Irish independence and in the historic Easter Rising rebellion, and his death before a British firing squad. We also talk about Connolly’s time in the United States where he organized for the IWW. And we discuss the history and historical significance of radical comics and graphic histories and the fundamental role in their development played by  Austin-based comix artists Gilbert Shelton, who pioneered much of his work in The Rag, and Jack Jackson (Jaxon).

Austin-based comix artists Gilbert Shelton, who pioneered much of his work in The Rag, and Jack Jackson (Jaxon).

Listen to the podcast of our interview with Paul Buhle at the Internet Archive or on the player below:

The Irish socialist who organized an uprising

[This article by Paul Buhle was first published by Truthout on April 25, 2016, and is posted here with permission of Truthout and the author.]

Why should we care about a failed independence uprising that occurred 100 years ago on April 24, led by Irish rebel James Connolly?

It’s a question answered within the pages of A Full Life: James Connolly the Irish Rebel, a graphic remembrance of Connolly illustrated by artist Tom Keough that I helped bring into the world.

It’s also a question that I might not have asked myself if I had not been in Dublin, Ireland, the day before Ireland’s marriage equality vote in May 2015.

The throng of young people in particular, eagerly distributing leaflets, cheering each other with smiles, waves, and songs, was something to see. Same-sex marriage was clearly to be approved by a massive margin across the Republic. A literature table and some very grouchy characters represented the official, deeply anti-LGBTQ views of the Catholic Church in Ireland. The Catholic Church, with its views on divorce and much else, has long been utterly dominant in the Republic of Ireland, but has more recently been discredited by reports of child sexual abuse committed by priests and sex scandals involving clerics, and by the emergence of a new, more secular generation.

By May 2015, the solemn-faced devotees almost seemed harmless — remnants of an unpleasant and widely regretted past. When the vote came, the church politicians carried only one county. Ireland had come into modern times. Not quite times for a wide-ranging discussion of James-Connolly-style socialism, however. That remained for the future.

Something equally remarkable and unpredicted for 2015 happened in the United States. Here, Sen. Bernie Sanders began talking up one of Connolly’s great admirers, Eugene V. Debs. Before Sanders rekindled public interest in this topic, Debs — the most beloved socialist of U.S. history — seemed to have vanished. A historic site devoted to Debs exists in Terre Haute, Indiana, and every now and then, the public hears once again about how Debs won nearly 1 million votes in the 1920 presidential election while campaigning from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary where he was being held as a political prisoner.

The public in Ireland has never forgotten the story of James Connolly.

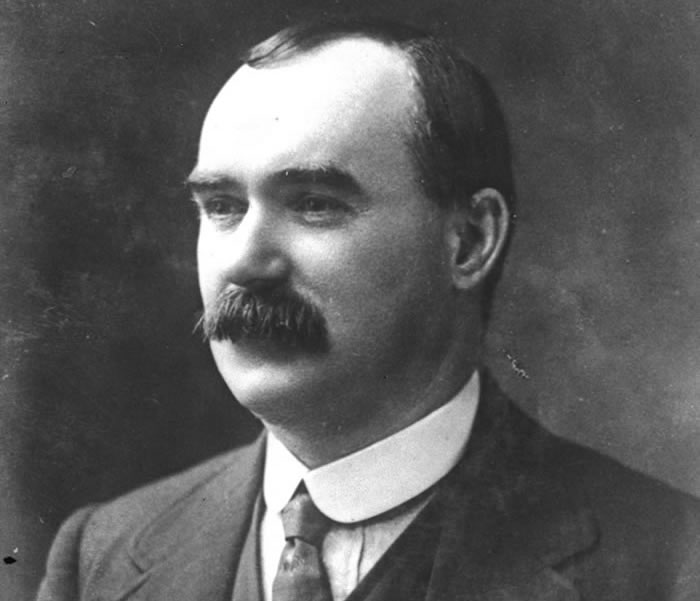

By way of contrast, the public in Ireland has never forgotten the story of James Connolly (1868-1916). Statues, portraits, inscriptions, assorted celebrations, songs from Connolly poems and songs about Connolly are recited or sung in Irish taverns by scores — all these seem available in any season. The run-up to the centenary of Connolly’s failed revolt for independence naturally offers a special case.

Connolly, actually born in Edinburgh, Scotland, among Irish immigrants seeking industrial labor, became a teenage factory worker and then British soldier until he managed a permanent AWOL, and then he became a socialist agitator and editor. Notorious in 1898 for leading a nationalist protest against a visit by Queen Victoria (among his fellow nationalists were poet William Butler Yeats and Maud Gonne, “the most beautiful woman in Europe”), Connolly continued to educate himself to an extraordinary degree. Meanwhile, he wrote immensely appealing, deeply sentimental class-conscious poetry. And then, broke as usual and with a growing family to feed, he abandoned Ireland for the United States.

On this side of the ocean, Connolly became an Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer, founded the Irish Socialist Federation and published its lively tabloid, The Harp, while writing furiously and traveling widely as a socialist lecturer. In 1910, Ireland called him home.

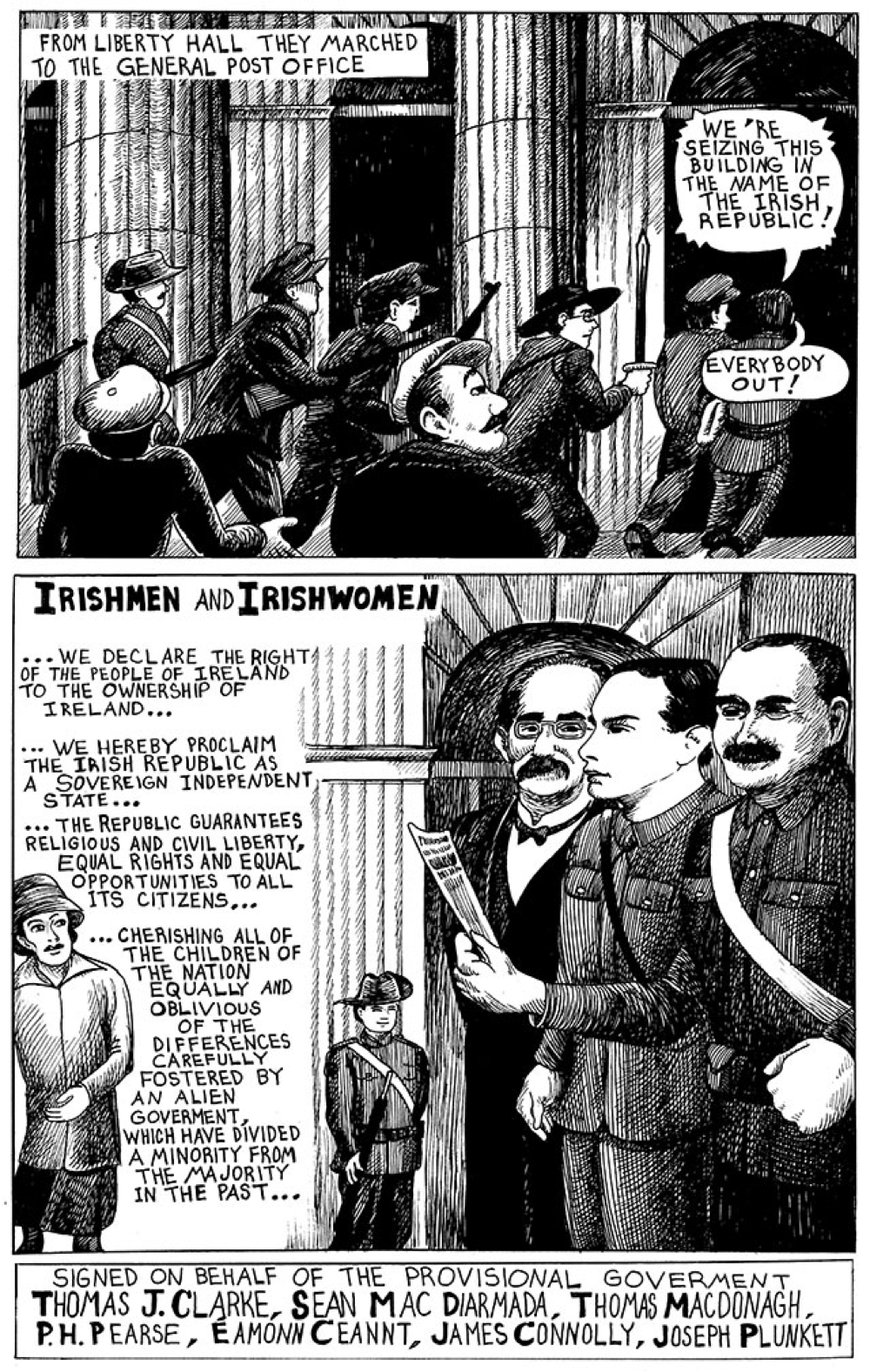

His extraordinary volume, Labour in Ireland — a historical inquiry into the workings of empire rivaling Marxist (or other) anti-imperialist analysis anywhere at the time — had as much as predicted catastrophic war between the rival empires. How right he was, and what conclusions to draw for Ireland’s quest to throw off the British yoke? “England’s adversity is Ireland’s opportunity,” according to the old adage. Against his own former reasoning that Irish capitalism would be no better than English bondage, he threw himself into plans for an uprising — the doomed uprising (or “Easter Rising”) of 1916.

Anticipations that the countryside would rise with the population of Dublin — or even that the poor population across Dublin itself would rise — proved worse than false. Within days, the Easter Rising was crushed. A badly wounded Connolly faced execution along with his comrades. But that would not be the end of the story, of course.

The British suppression was brutal almost

beyond description.

The British suppression was brutal almost beyond description. Wholesale murders, torture and the full gamut of horrors stirred Irish sentiment as the rebellion had not. In the end, the British seemed glad to get out, and in 1922, the Free State emerged. The former colonialists retained the northern six counties with mostly Protestant populations, planting the seed for future strife bordering upon internecine guerilla warfare, and for repressive state violence by British authorities.

The Irish Republic, nurturing nationalist resentments but run by a repressive clerical clique and a pack of corrupt politicians, remained a site of heroic memories alongside a most unheroic present. Connolly, the socialist ghost, inspired labor activists and a persistently fragmented left, recalled, if distantly, by the 2014 Ken Loach film Jimmy’s Hall. His mustache glowers out from photos and paintings, a sign of fierce resistance. But perhaps Connolly is best remembered as the autodidact theorist and inveterate sentimentalist who comes to life again in popular culture. Hence the James Connolly comic, A Full Life, with the artwork of a veteran Irish-American activist and of myself, an aging editor.

This article copyright Truthout.

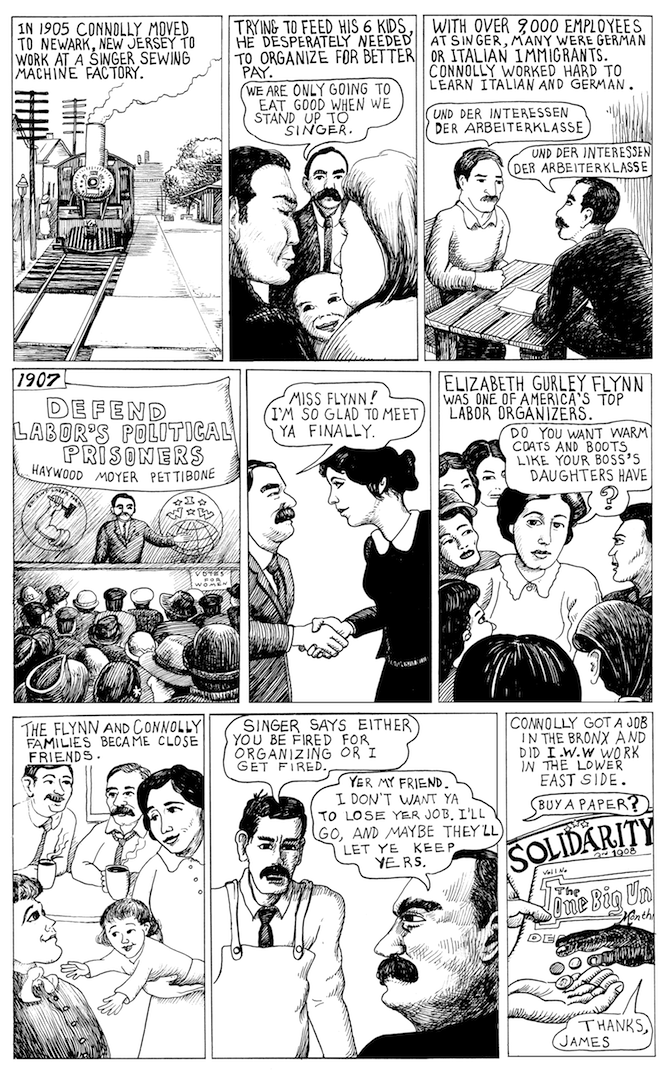

Image from A Full Life: James Connolly the Irish Rebel, published by PM Press. Drawn by Tom Keough and edited by Paul Buhle.

Afterword: James Connolly in history

[This “Afterword” by Paul Buhle appears in A Full Life: James Connolly the Irish Rebel, which Buhle edited, and is reprinted with permission.]

Renewed recognition of James Connolly’s life and work, his triumphs and his tragedies, is very much on the agenda in 2016, and not only for scholars. The centenary of the Easter Rising (or Rebellion) splashes Connolly’s face and borrowed memories of his martyrdom across the whole Irish diaspora. Fact and legend, always abundant and overlapping in the Connolly saga, reemerge with a new vividness. The real story is larger and has come, at least to some extent, back into view for us all.

The 2015 republication of a British feminist classic, Sheila Rowbotham’s Friends of Alice Wheeldom: The Anti-War Activist Accused of Plotting to Kill Lloyd George, offers one fascinating avenue for renewed speculation about the breadth of Connolly’s thinking and his influence. Glasgow, Scotland, during the 1910s, was a beehive of socialist activity, heavily impacted by workplace conflicts, pressure for women’s rights, the approach of War, and the presence of a suffering Irish proletariat. None of these causes found Connolly and his ideas absent.

Connolly had spent precious years from 1902 to 1910 in the U.S., much of his time and effort evoking the grand vision of the IWW: socialism emerging as the “new society within the old.” Breaking with the traditions of insular or sectarian socialism, propagandizing but unable to reach the working class successfully, Connolly urged the formation of broader, more comprehensive radical movements. Arriving back in Ireland, he energetically joined the campaign to have Irish children included in the British Act of Parliament providing funds for feeding the impoverished. Likewise, he stood proudly on platforms with non-socialists, urging the legalization of votes for women, a demand that “pure” socialists considered a mere bourgeois reform. His 1915 essay in the Irish Worker, simply titled “Woman,” contained this vivid phrase, “None so fitted to break the chains as they who wear them, none so well equipped to decide what is a fetter.”

Connolly figured not only as an agitator for radical reform but a monumental visionary.

From Dublin to Glasgow (where the antiwar movement was weaker, but the woman’s rights campaign stronger than in Ireland), Connolly figured not only as an agitator for radical reform but a monumental visionary. He placed aside old prejudices against religious people joining or supporting the socialist and labor movements, insisting that one day in the future, the reactionary views of even the Catholic Church would fall away as the class struggle accelerated and capitalism crumbled.

Recent scholarship has accorded Connolly further significance in his time and assorted locations. By seeing in Ireland’s fate a microcosm of Empire’s victims, the self-taught worker-intellectual looked ahead to the expansion of Marxist themes in the twentieth century and beyond.

Badly outnumbered within the Second International, but joined by the likes of Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin, a circle of Dutch socialists and American socialist leader Daniel DeLeon, Connolly placed an urgency on the issues of Empire and revolt. After the revolutionary wave in Europe receded (and Connolly himself gone), struggles against Empire came out of the Marxist background and into the front row.

A generation after Connolly’s death, his successors were working feverishly to explain to socialists and others the changing reality of the world scene. In the writing and political activity of C.L.R. James and others, the central importance of Africa, Asia, and Latin America for the future of the socialist movement became clear. Rosa Luxemburg had been the first to argue that capitalism might well extend its life for generations through robbing and devastating the undeveloped world.

The British Empire, ruler of the seas, had long ago begun by enslaving island neighbors.

Opposed on principle to any nationalist movement, Luxemburg herself could not appreciate the full weight of the Irish Left and its responsibility to history. The British Empire, ruler of the seas, had long ago begun by enslaving island neighbors.

Connolly, some would now argue, had been the earliest of any revolutionary thinkers in the “colonies” to formulate an anti-imperialist narrative stretching across centuries. Foreshadowing the activism of Che Guevara and the writings of Frantz Fanon, Connolly sketched the potential of a solidarity that could break the power of Empire and end the nightmare of capitalism. He had the experience, the legacy, but also the self-taught intellectual power and determination as writer to make the decisive connections.

Labour in Irish History (1910), drafted in the U.S. but published only after his return, could easily be described as Connolly’s most profound historical but also theoretical text. As he looked back across the centuries, he saw clearly what Marxist theoreticians in the 1960s-80s would come to describe as forced “underdevelopment,” the stifling of a domestic economy by the purposeful efforts of the invaders and occupiers.

Image from A Full Life: James Connolly the Irish Rebel, published by PM Press. Drawn by Tom Keough and edited by Paul Buhle.

A premodern, thinly-settled society with competing mini-dynasties offered little organized resistance to the military campaigns of successive invaders, prominent among them the Normans and centuries later, Cromwell’s army. The imported English plantation economy, like all imperial settlements from South Africa to the West Bank, brought religious and racial bias — from the English point of view, the Irish were definitely a lesser race — along with a new dominant religion and economic-political estates. Thereby, Ireland was reshaped to alien purposes, and repeatedly reshaped. Farming became heavily commercial and industry blossomed. The wealth thus created, like the wealth created by the production of sugar and cotton in the West Indies, was brought “home” in large quantities. English lords and ladies lived and dined from the ill-gotten profits of their ancestors or by their own location, temporary or long term, in supposedly barbarous Ireland. English families in permanent residence scorned the native population and culture as nearly subhuman, worthy of starvation and brute force. The “culture” that these aristocrats appreciated and promoted had no relation to the true cultures of their borrowed lands.

From the English point of view, the Irish were definitely a lesser race.

It would not do to push this comparison too far. Abused and exploited, the Irish were not slaughtered directly in large numbers — leaving aside the vast starvation during the Potato Famine — and they enjoyed the advantage or dubious privilege of exporting themselves to anywhere they could live…. as lower-class white people. Today’s scholars add that if Connolly grasped the social and economic significance of colonization, he had scarce formal training, by contrast to the college-educated and socialist classroom hardened Luxemburg, to base his insights. He made few direct references to the peoples of Africa or Asia, except to denounce the British role across the colonized world. But he memorably hoped a prospective nationalist revolt within India might bring a revolt of the Irish against the same colonial masters.

Any analysis of Connolly’s limitations, moreover, misses the point in several important ways. Autodidact revolutionary that he was, he made full use of his opportunities and his milieux. In his American days, he first associated himself closely with the Socialist Labor Party and its press, the Daily People newspaper, which carried much information about the role of imperialism in the world. The SLP itself dwindled after a bitter conflict within the IWW, but its opposition to immigration restrictions (sought by craft union leaders, especially in the United States) and the repeated call for international support of “native” revolts arose regularly in the pages of the paper. Thereafter, his closest allies could be found in the Charles H. Kerr Company, which published several of his short works, and the associated International Socialist Review, which held the banner of anti-imperialism high.

Far from simple-minded in his critique of British imperialism’s effects upon the oppressed Irish, Connolly could even see, as few others, how Irish men and women could be tempted to join the grand imperial army, and did, to their moral corruption and material benefit. It was a great leap forward that has not been appreciated, so little was Connolly’s advanced thinking known or appreciated outside Ireland and Irish proletarian colonies abroad.

Perhaps none of this hard thinking could have been brought to fruition without Connolly’s keen moral and emotional sensibilities, so deeply rooted in his Irishness, and so brilliantly expressed in his newspaper, The Harp. Modern and postmodern thinking has little room for the sheer sentimentality of Connolly’s lyrics, written to accompany traditional songs. They were written to rouse workers to common struggle against the capitalist oppressors, but also drew upon the most tender sentiments of family feelings, and the great urge toward a better society, an urge maintained through great difficulty with the dream of what that better society would surely bring. Songs of Freedom by Irish Authors, the five-cent edition prepared by Connolly and published by an Irish-American firm in 1909, delivered inspiration to lift the hopes of every reader (and singer) for what humanity could become.

[Radical comics publisher Paul Buhle, a former senior lecturer at Brown University, was active in the civil rights movement and worked with SDS in the Sixties. He was founding editor of the influential journal, Radical America (1967-1999) and his Radical America Komiks, produced in collaboration with underground comix pioneer Gilbert Shelton of Austin, helped introduce the radical new medium to the American Left.]