Does the U.S. embargo help the Cuban government?

…every system is a series of interlocking, intractable problems, where consequences, intended and unintended, inevitably wall off potentially desirable effects from delivering their intended promises. I cannot think of a system, certainly including my own, which is not beset by contradictions and dilemmas which are the direct results of policies designed for the best of reasons.

By Peter Coyote / March 2, 2009

HAVANA — Interesting and informative as it may be, meeting virtually the entire world of cigars, running around relentlessly, speaking another language, eating different food and writing hundreds of words a day is exhausting and it’s time for a day off. I decide to visit the town of Coghinar, the site Hemingway chose as the setting for “The Old Man and the Sea.” I thought it might be nice to sit in the sun, on a beach.

Leaving Havana, on a wide clean road, in a car that appears to be a relatively new Audi A-6, the absence of any evidence of shock absorbers serves as a reminder to “stay awake” and “be observant,” transmitted through my lower back and kidneys like body-blows.

Driving on roads with virtually no traffic is like being returned to a state of grace in America of the 1950s. The way is wide and broad and there is absolutely no advertising. It’s refreshing. There are the odd signs of propaganda — reminding us of the plight of the Cuban 5, that Che and his example lives forever, that Chavez of Venezuela is a good friend to Cubans etc. Despite being clear and bright and usually cryptic, a few are too dense for me to grab in my limited Spanish. One for instance, announces that “two hours of the blockade would” (and here I lost it for the instant it took to drive by) “all the Braille in Cuba.”

For the most part however, Cubans have not considered the concept that all “public” space be made available for private exploitation, which, if you think of it, is exactly what advertising accomplishes. Before Freud’s nephew, Edward Bernays, used his uncle’s work to delve into the unconscious of consumers (dedicating his skills to successfully convince women to begin smoking) and before he had come up with the idea of re-branding his efforts as “public relations,” folks simply called it what it was quite nakedly — propaganda. In its most elemental form, it allows a corporation to place between you and the view of any scenery or vista a psychologically adroit argument (in visual coding) to buy something you probably do not need. Since it’s public space and “free,” and since Americans are a freedom-loving people, there appear to be no limits on the concentration of media messages allowed even if an actual forest is replaced by a virtual forest of brand-name exhortations. It’s “free.”

In Cuba however, the road is lined with dense green woods, or pastures, shanties, sometimes stately homes, herds of goats, or lines of distant palms. These views are uninterrupted by bright, colorful, sexually suggestive photographs of attractive people interacting with sexy products. Perhaps it’s because there appears to be so little money here, but I barely saw an inducement to buy anything, and, for one, found it restful. All the Cubans I saw were clothed, shod, and well-fed. (Though to be fair, I never saw a fat person in Cuba — unless they were a foreign visitor.) They must have purchased these items somewhere, but except for my granddaughter’s present, I saw very few stores. Cuban cars, in many cases, were newer than the hand-painted relics I find so attractive here and remember fondly from my youth. They too came from somewhere, but I never saw any of those “where’s” or any of the automobile brands advertised.

A short hop off the main road, we pulled onto a sandy knoll in the La Playa del Este region, under a palm tree, near a little bohio that sold pop. The vista is decidedly Fellini-esque with large open spaces, a single inexplicable industrial-sized building off in the distance, and a single person crossing an expanse of dried lawn. There were one or two other cars about, but no surf shops, condos, jet-ski rentals, scuba-tours, marlin tournaments, or motorboats advertised. The sand was fine and white and extended as far as I could see in two directions and the water was a magnificent collision of two bands of very distinct color next to the shore — a milky jade green; and approximately 15 feet out it turned immediately into an intense lapis lazuli extending to the horizon. I could sense the whetting of corporate knives as international hotel executives plotted to turn such a beach into a replica of the Zona de Hoteles in Cancun I found so depressing. All that potential capital going to waste; all that beauty unexploited. “These Cubans are too dumb to realize what they have, Fred.”

I rented a chair from the owner of the bohio for a peso and plotzed to look at the horizon awhile. To my left, about a hundred yards away, two men body-surfed in the swells with evident relish. To my right, an equal distance away, two people lay on the sand taking the sun. That was it. Sun, sand, gorgeous water, an old white plastic beach chair, y nada mas, as they say down here. The wind was brisk, and occasionally grains of sand stung my cheeks, but I sat for a lovely uninterrupted, unhurried hour. The week to date, however, had generated too much internal momentum to sit longer. I returned the chair and moved on.

We arrive in Santa Maria de la Mar, which may be where all the ugliest housing projects that the Russians ever gave to Cuba came to die. They are impersonal, vast as projects in the slums of the States, only more decrepit. It is unsettling to see them and hard to consider how anyone could be happy or even dream of beauty in such an environment, but my guide, catching my cultural assumptions, reminds me they are “Mejor que nada,” much better than the “nothing” that most poor Cubans possessed before the Revolution. I realize that once again, attempting to view Cuba through lenses appropriate to the United States can easily lead one astray, and that for people who grew up on dirt floors and under palm-thatch and open walls, even gray-concrete with running water and a bathroom is an improvement. Once again, I remember that I have not seen one homeless person in all of Cuba, and if it takes these ugly Russian buildings to accomplish that, I will shut my mouth about it.

From Santa Maria we descend into the little fishing village of Coghinar. Two men are playing guitar and singing on a porch opposite where we park. One is a wiry man with honey-colored skin about 50. His companion is white and stooped, probably in his late 70s. They play and harmonize beautifully, and the darker man acknowledges my interest with a lifted-chin salute and a smile.

The main street slopes down to the sea, and even from several hundred yards away, I can see the white pergola with pink-trim, which David tells me houses a bust of Ernest Hemingway. I start in that direction, when an old woman stops me. Pointing to my cigar she says, “Hay una Cohiba.” I stop to chat and show her the black band of the Gran Reserva, which she has never seen. (When the cigar went out last night, I put the remaining half in a Bolivar aluminum tube and saved it for today.) She tells me that she worked in the Cohiba factory for 25 years, wrapping the bands on the cigars and that she thought it was fine. Life now is hard, she confesses, and shows me her swollen feet and says something about “adult diabetes.” We listen to the music a bit together, and she waves goodbye as I walk on.

A bit farther down the street, a house is having some construction done. There are concrete blocks and piles of sand and cement blocking the driveway of a sweet and modest house in good repair. A handsome man in his early forties stops me and points. “You’re an actor,” he says and I nod, yes. Laying his hand lightly on my shoulder as a request to wait, he calls loudly to his wife inside to “come out and see who this is.” A younger woman with an open and expressive face comes out and smiles in surprise. She takes my hand and we chat a moment. Both she and her husband know some of my films, and the TV series, “The 4400,” is currently playing on Cuban TV. (Of course, because the U.S. refuses all relations with Cuba, they simply download such shows off the satellites and see them for nothing.)

The man’s wife then says with evident pride, “My husband is José Modesto Darcourt.” David explains that José was a champion Cuban baseball player who pitched for a team called The Industrials. I am embarrassed to have had the advantage of the distribution machinery of American culture. He knows who I am because America’s reach extends into his living room, yet because we have no reciprocity with them, I had no idea I was in the presence of a hero. I was just “well-known,” in Cuba, he was once a god.

We talked awhile and when I told him why I had come, he pointed down the hill in Hemingway’s direction, smiled and shook my hand again. His wife smiled too, clutching her apron, and moved sideways to stand beside José, proud of her husband, proud of her house, and perhaps even proud to live in a town where neighbors serenade one another and “movie stars” can suddenly appear in the street.

We walk down to the wharf at the end of town and I bow to Hemingway and take a photo of his statue with a dog sleeping at its base. Unlike Odysseus, who traveled the world and returned home and whose dog died upon recognizing him, it is this fine writer, immortalized all over Cuba, who has died, and the skinny, dusty, and undernourished dog endures, much like the rest of Cuba.

On the way back to town, we pass more cheerless, three-story concrete Russian apartments, stained with a dark grey mold. Cultural bias aside, I can’t understand how the Russia that produced Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and Turgenev and Gogol and Chagall and Kandinskii, Moussorgsky and Rachmaninoff and Rostropovich and the Bolshoi Ballet; poets like Anna Tsvetaeva and Mandelstam; which constructed the fanciful multi-colored, turreted buildings of Moscow and St. Petersburg — how could it have contributed such ugliness to the world? I’m stunned by it, will never accept it, but I can understand why it appeared to be a necessity. For that reason, at least in Cuba, I’ll keep my opinions about them to myself.

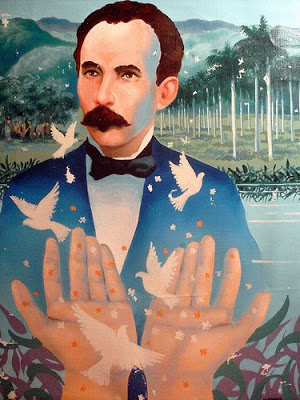

Back in Havana, we walk awhile at the Plaza de José Marti, a popular gathering spot where people argue sports and politics in loud and energetic exchanges. It’s hard to estimate the meaning of Marti for Cuba. Widely revered as a poet and an intellectual, a soldier and resistance fighter, a lover of women, and a politician, Castro acknowledged him before the entire country when he addressed it after the Revolution and told the Cuban people that he had simply finished what was begun by Jose Marti.

Born in 1853, he lived a full, active, politically engaged life, 10 years of which he spent in New York City. Statues of him are everywhere, and even the dictator Batista had a statue of him in his office. (Hypocrisy is the tax that vice pays to virtue.) He dedicated his entire life to ending imperialism and driving the Spanish from Cuba, but incidentally found much about America’s freedom and immigrant society to love even as he feared its global reach. He died in a suicidal two-man charge against Spanish positions at the Battle of Dos Rios and when the Spanish soldiers discovered who they had killed, they were afraid to burn his body for fear that his ashes would enter their throats and choke them.

No me entierren en lo oscuro

A morir como un traidor

Yo soy bueno y como bueno

Moriré de cara al sol.”(“Do not bury me in darkness / to die like a traitor / I am good, and as a good man / I will die facing the sun.”) — Marti.

We have lunch at a restaurant, in another barrio which was called (I think) La Paila, though the waiters wore aprons embroidered with other names like “Casillero del Diablo.” As we nibble on the traditional fried Malanga crouquets, a slender American man with a beard, casually dressed, in his 50s introduces himself as Bob Israel. I’m momentarily befuddled until I realize that his son Jesse is one of my son’s best friends in New York. Bob sits a moment and explains that he’s here with a group from Dreamworks Studio (think Stephen Spielberg), being led on a tour by one of their executives who loves Cuba and loves introducing people to it. They are here under license (meaning that the government cannot fine them or confiscate their property) doing some sort of humanitarian work, but I am too surprised by the sudden intrusion of Hollywood into Havana to fully register what it was. We chat about our kids, thousands of miles away, until his food arrives and he rejoins his group, and my other friend (who I’ll leave nameless due to the nature of our conversation) and I pick up a thread we’ve been discussing throughout my trip.

Orelio (a name as good as any other) has previously explained to me that Cuba now imports sugar and tomatoes, crops which would grow here effortlessly, along with a host of other things that require them to spend precious currency. I cannot understand why. Why grow tobacco and not tomatoes? Is it only a question of which brings in the most currency? If there were more food available obviously the state would require less money. Why not grow it?

Orelio drops his voice — and I get the first intimation of why some refer to it as “a police state,” though I have seen no evidence of surveillance, or oppressive police presence, or any undue deference of the people to their fellows in uniform. Still, his gesture was reflexive, defensive in nature and I did not understand the situation fully enough to know whether he was keeping our conversation private out of respect for the people at other tables who might hold other opinions, or because he was in some way afraid.

He points out that the revolution will not allow brokers of any kind. Consequently there is no agency, public or private, to buy food from the farmers and sell it to the state. They have been forbidden, because they would inject profit into the process of sustenance and, inevitably raise the price of food and create a class that “lives off the work of others.” Food must, for a number of reasons, be kept cheap, and so the state buys directly from the farmers at a very, very small margin. This lack of ability to make money from their work acts as a disincentive for the farmers from growing much more than they need, or working overly diligently for so little money. It is honestly, the first time I have ever given any credence to Republican assertions that without money as an incentive people will not work. It never made sense to me because I enjoy writing and performing, by and large, and so do most of my friends. We have all done our work free before, and so the “incentive” argument has always seemed like a thin soup. As in most things, I can see that no one side of an argument ever owns the entire truth.

Farmwork is tough. It demands long hours, patience, dedication, endurance and hardship and it is pretty clear that people work for more than the simple human pleasures of interacting with the soil. It is intractable. If the government allows markets to develop and the price of food to rise, food may be plentiful, but it will also be too expensive for the majority of Cubans. It will also become plentiful at the expense of creating hierarchical classes of people, a condition which is anathema to the sentiments of Fidel’s revolutionary generation. Remember again the natural opposition of “freedom” and “equality.”

It’s clear that every system is a series of interlocking, intractable problems, where consequences, intended and unintended, inevitably wall off potentially desirable effects from delivering their intended promises. I cannot think of a system, certainly including my own, which is not beset by contradictions and dilemmas which are the direct results of policies designed for the best of reasons. Take the car, for instance. Who could have predicted that this vessel which offered freedom and independence, generated millions of jobs, virtually an entire economy, and nearly uncountable national wealth would wind up controlling our lives, architecture, transportation design, poisoning the planet, threatening our national security and independence and collapsing a major wing of our economy?

Americans have been trained to criticize socialist countries for their problems, but those cultures arrived at their problematic conditions the same way we did…pursuing ideologies and intentions that ensared them in unintended consequences. I’m not trying to make all problems equal, either morally or practically, but one can understand, just by examining the question of sharing food, that the dilemmas are universal.

Orelio continues, shocking me by suggesting that the embargo may serve the Cuban government with a ready-made excuse for its failures. “As things stand now, the embargo actually helps the government,” he suggests, by being the source of all things miserable in Cuba. Should it end suddenly, then people may wonder why buildings are so decrepit, why the environment is not better cared for as it should be, or why Cuba is forced to import so much of what they need. He is open, of course, to the possibility that ending the embargo might also change all those examples for the better, but he offers as evidence the following story:

A Miami Cuban counter-revolutionary group had been flying into Cuban airspace, filing false flight plans with our government, and dropping propaganda leaflets over the population for many years. The Cubans did not like it and complained to the United States for years about these violations of international law, and airspace. They were very very patient about this insult to their sovereignty. One day, however, they had enough and shot down two planes killing all aboard. “When did they shoot down the planes?” he demands. When Bill Clinton was in office and there were talks afoot to relax travel and remittances and the like, he said. Clinton was going to support liberalization of relations and it was then that the Cubans shot down the plane. That act made it impossible for Clinton to continue his liberalization efforts and gave sustenance to all Castro’s enemies in Congress, insuring (according to Orelio) that the embargo remained in place. Knowing the degree to which Clinton was dependent on the Cuban vote in Florida for his presidency, it’s hard to believe he was intending to be too liberal, but even the fact that this hypothesis is believed by (at least one) of the Cuban people, it’s informative of tensions and difficulties in the system.

“America could invade Cuba any time it wanted without a problem,” he continues. “They never will. They don’t want to take care of 11 millions Cubans” for one thing, and for another, Cuban boats patrol the maritime borders — one every five miles to interdict drug runners and (according to Orelio) escapees to the United States. “Do you know how much it would cost the United States to do such patrolling to keep drugs away? Do the math.”

Orelio is persuasive and it is less important whether he is correct than it is that he is highlighting facets and complexities of the American-Cuban interface that are never publicly discussed. There are others who probably have direct access to the information which could prove or disprove these assertions, but without open dialogue and frank exchange they never surface into public discourse and citizens of both cultures are the losers.

© 2009 Hearst Communications Inc.

[Peter Coyote is an actor and author. He was active with the San Francisco Mime Troupe and the Diggers in Sixties San Francisco. Sleeping Where I Fall, his memoir of the 1960s counter-culture, will be re-released in May 2009. This article was originally posted by Peter Coyote on Feb. 26, 2009.]

Source / SFGate

Every government can help Cuban government by removing duty from it’s top quality products like cohiba. Now a days, every one is a smoker. this is a great way for a government to support some other government. Cuban government can apply tax on Cohiba more than every. And other governments can remove duty from Cuban Products. Simple