“Mexico’s crisis manifests as violence, but it is rooted in the corruption and weakness of the state.” — Max Fisher, Amanda Taub, and Dalia Martínez, 2018

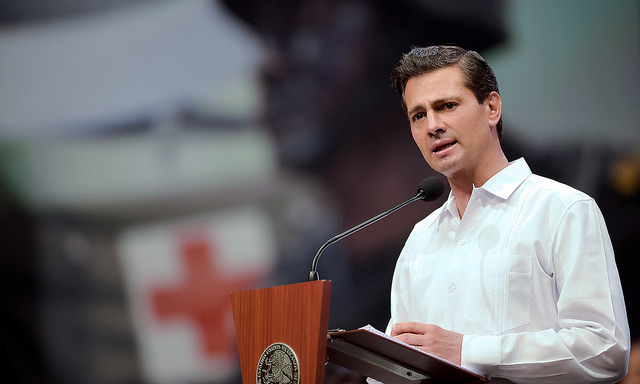

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto, 2017. Image from Flickr /

Creative Commons.

Philip Russell will join Thorne Dreyer on Rag Radio, Friday, February 9, 2018, to discuss this article and the Peña Nieto presidency. Rag Radio is a syndicated radio program that first airs on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin and is streamed live here.

Philip Russell will join Thorne Dreyer on Rag Radio, Friday, February 9, 2018, to discuss this article and the Peña Nieto presidency. Rag Radio is a syndicated radio program that first airs on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin and is streamed live here.

Philip Russell writes about Mexico for The Rag Blog. This is the fourth in his series about the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto.

The good news for Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto of the Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) is that during 2017 — his last full year in office — his approval ratings doubled.

This was in part due to his not making any major missteps relating to the big events of the year — two strong earthquakes and the ongoing renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Peña Nieto’s improved approval ratings were also due to, as The New York Times reported in December, his administration’s spending nearly $2 billion to buy ads extolling various agencies of his government. Of course there’s a quid pro quo. Media outlets which refrain from or soften criticism of government receive an ad revenue stream. Critical media don’t receive government ads.

The bad news is that Peña Nieto’s approval ratings only rose from 12% to 25%.

The bad news is that Peña Nieto’s approval ratings only rose from 12% to 25% during 2017 — figures that are record lows for a Mexican president. Despite his $2 billion PR campaign, in a poll published by the newspaper Reforma in December, 75% of the Mexican public declared Mexico was on the wrong path.

Disapproval of Peña Nieto’s performance outweighed approval in each of the eight areas the poll considered — health, education, employment, security, economy, and combating corruption, poverty, and organized crime. In a separate poll, known as the Latinobarómetro, only 18% of Mexicans declared themselves to be satisfied with the way democracy was functioning in their country — a figure below Venezuela’s.

Of the various shortcomings of the Peña Nieto administration, corruption is the one which affects virtually all Mexicans. The problem clearly worsened under Peña Nieto, as indicated by Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index 2016, which found that Mexico had slipped from 105th place in 2012 to 123rd. That is to say, of the world’s nations, 122 were less corrupt than Mexico.

The administration has sent mixed signals about concern for fighting corruption.

The administration has sent mixed signals about its professed concern for fighting corruption. Santiago Nieto, the special prosecutor for electoral crimes, was dismissed, supposedly for violating agency protocol. His real offense, as political scientist Denise Dresser noted, was his violating omertà — the Mafia vow of silence. He had launched an investigation into the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht’s possibly having paid millions in bribes which were used to finance Peña Nieto’s 2012 electoral campaign.

A possible sign of vigor in the anti-corruption campaign is the jailing of six former governors on corruption charges. Another former governor is on the lam. In January of this year, Roberto Borge, former governor of Quintana Roo, was extradited from Panama to face charges of plundering his state’s government. His favorite ploy was selling state-owned land to friends, relatives, and state officials at far below market prices. The land then would be resold at market price, with Borge and the first purchaser sharing the profits. By one estimate he defrauded his state of more than $500 million.

His capers were particularly harmful to Peña Nieto, who had hailed Borge as emblematic of the new, reformed PRI when he became governor at age 32. If these prosecutions continue after this summer’s elections, it will indicate unusual vigor in combating corruption.

Insecurity affects Mexicans from

all walks of life.

As is the case with corruption, insecurity affects Mexicans from all walks of life. With 25,339 murders, 2017 was the bloodiest year of this century. Great Britain’s Institute of Strategic Studies declared Mexico to be the second most violent nation on earth. This level of violence reflects the fact that, as political scientist Lorenzo Meyer observed, “None of the last three administrations has been able to successfully confront insecurity, nor even offer a realistic solution.”

One of the positive trends the Peña Nieto administration touts is job creation. However employment statistics indicating the lowest unemployment rate in a decade mask another chronic problem — poverty. Poverty, even among the fully employed, results from a trend toward more poorly-paid jobs and fewer well-paid ones. Of all the Latin American nations, Mexican wages, as opposed to profits, form the lowest percentage of gross domestic product. According to government figures, 63 million Mexicans live in poverty — 11 million more than 25 years ago.

Poverty in not the result of Mexico’s being a poor nation. It is the result of concentrated wealth. According to the U.N. Economic Commission for Latin America, the top 10% of Mexico’s population amasses two-thirds of its wealth. Bloomberg reported the wealth of Carlos Slim, Mexico’s richest person, rose by $12.5 billion in 2017 alone.

Mexico’s wealth is also skewed regionally.

Mexico’s wealth is also skewed regionally. The six states bordering on the United States all have above average per capita production. The southern states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Chiapas are the poorest. Per capita income in Chiapas, the site of the 1994 uprising by the Zapatista Front for National Liberation (EZLN), declined by 0.3% annually between 2003 and 2016.

Mexicans are understandably dissatisfied with their country’s economic performance. Many voted for Peña Nieto based on his promise of 5-6% growth. Instead they have seen growth during his term average 2.1% — roughly the rate of population increase. In terms of economic growth, Mexico is lagging behind the rest of the world. In this century, the economies of Russia, India, South Korea, Australia, and Indonesia have outperformed that of Mexico.

Promoting the use of renewable energy has been one of the few widely approved steps Peña Nieto has taken. Auctions have been held for solar and wind energy. Low bidders were awarded long-term contracts to supply clean energy. Offsetting these clean energy measures has been a controversial opening of the oil sector to private companies — foreign and domestic. If the efforts to attract private capital into oil production are successful, increased CO2 emissions resulting from burning hydrocarbons will offset the reduction from clean energy generation.

Unfortunately for Peña Nieto, these

trends will form his legacy.

Unfortunately for Peña Nieto, the trends noted above will form his legacy. This year pundits and políticos will be focused on the July 1 elections, which will select the president for the 2018-2024 term, as well as members of congress, the mayor of Mexico City, eight state governors, and local office holders.

The incumbent Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) and its well-honed political machine will struggle to overcome the party’s sordid reputation, which has been dragged down by Peña Nieto’s performance. The PRI’s main challenger is third-time presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) — the left’s best hope of defeating the PRI. Other parties have formed an awkward left-right alliance in hopes of blocking both AMLO and the PRI.

Finally, for the first time, independent candidates will be allowed on the ballot. One or more of the independent candidates may further divide the electorate in the one-round election where the winner may well receive less than a third of the vote.

[Austin-based writer Philip L. Russell has written six books on Latin America, including The Essential History of Mexico (Routledge, 2016), and is the editor of the Mexico Energy News.]

Also see:

- “2016: Another bad year for Mexico’s Peña Nieto” by Philip L. Russell, Jan. 18, 2017

- “Mexico’s Peña Nieto at midterm” by Philip L. Russell, Jan. 4, 2016

- “A third of the way: Peña Nieto’s first two years” by Philip L. Russell, Dec. 8, 2014

- Philip Russell’s Rag Blog articles about Mexico and Mexican politics.

- Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Philip Russell.

Philip, this is just so excellent. I don’t see enough of your work; I forget how good you are, man!

Clear and straight-forward. Gently enlightening. The way journalism is supposed to be.

I want to try to share this with some Belizean media, since Mexico is our neighbor to the north, and the Mexican and Belizean economies have many ties, not to mention the cultural, linguistic, and Official links.

Very nice; more, please!

Greetings. I want to add something to Philip Russell’s piece: Where he writes: “Promoting the use of renewable energy has been one of the few widely approved steps Peña Nieto has taken. Auctions have been held for solar and wind energy. Low bidders were awarded long-term contracts to supply clean energy. Offsetting these clean energy measures has been a controversial opening of the oil sector to private companies — foreign and domestic. If the efforts to attract private capital into oil production are successful, increased CO2 emissions resulting from burning hydrocarbons will offset the reduction from clean energy generation”, I want to mention that even this has provoked opposition because, apparently, of the massive scale of wind and solar operations and the use of eminent domain or just plain theft to take indigenous or communal lands out of agricultural production and into energy production. This is especially controversial in the state of Oaxaca.