The Port Huron Statement that Hayden drafted, a deeply intelligent critical analysis of American society, became the manifesto of a generation.

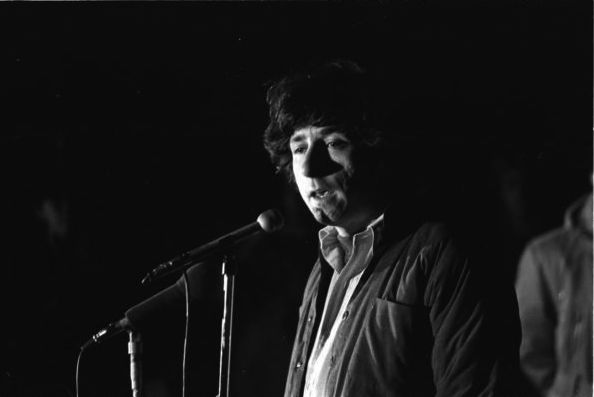

Tom Hayden speaks at the Vietnam Moratorium in Ann Arbor in 1969. Photo by Jay Cassidy, courtesy of Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan.

REMEMBERING TOM HAYDEN

Peace activist and spiritual leader Rabbi Arthur Waskow and activist and SDS vet Carl Davidson, joined Thorne Dreyer on Rag Radio, Friday, Oct. 28, 2016, 2-3 p.m. (CT), to discuss the life and legacy of Tom Hayden. Listen to the podcast here:

Peace activist and spiritual leader Rabbi Arthur Waskow and activist and SDS vet Carl Davidson, joined Thorne Dreyer on Rag Radio, Friday, Oct. 28, 2016, 2-3 p.m. (CT), to discuss the life and legacy of Tom Hayden. Listen to the podcast here:

Peace and justice activist Tom Hayden, founding spirit of SDS, principal author of the Port Huron Statement, and arguably the most influential figure in the Sixties New Left, died Sunday, October 23, 2016, in Santa Monica, California, at the age of 76.

Tom was a dear friend and colleague: a frequent contributor to The Rag Blog, a regular guest on Rag Radio, and a strong supporter of all our efforts.

This is one of several tributes to Tom Hayden we are publishing on The Rag Blog.

Tom Hayden, who died on Sunday, October 23, was one of the best of the change-makers who made The Sixties a transformative time, and who have kept going with verve and persistence through the half-century since.

What made him so much a leader? And what can we learn from him?

He was extraordinarily bright and extraordinarily focused — in his case, on building a movement to achieve the power to make profound social change. Yet — unlike the stereotype that many people have of the very bright and the sharply focused — he was not cold, stand-offish.

He liked people. He loved people. He brimmed and bubbled over with caring for individual people, not only for The People — whom he also loved. And he was clear that the goal of achieving power for a society of love and justice could be achieved only by using consonant means — means rooted in that love he felt for people and The People.

When he gathered with a small community of students in 1962 to create Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), he wrote what became the manifesto of a generation, the Port Huron Statement. It was a deeply intelligent critical analysis of American society, and a practical vision for making social transformation. Just as important, it spoke in a tone rarely heard from radical intellectuals: It treated the facts it cited not as “cold facts” but as “warm facts,” imbued with emotion, even with spiritual seeking.

Not just the words on paper but Tom’s face and body glowed with passion, with caring, with love.

Not just the words on paper but Tom’s face and body glowed with passion, with caring, with love. The students who gathered at Port Huron were able to create SDS because of that sense of loving community, so strong with each other that it was authentic when writ large into a thirst for a whole society that could lovingly care for all its members.

I met Tom during the Golden Age of SDS, when Tom and Todd Gitlin, Carol Cohen McEldowney, Paul Booth, Casey Hayden, Alan Haber, Marilyn Salzman Webb, Lee Webb were so brave and so brilliant that they drew me into my first arrests, drew me into fusing the profound intellectual work of Marc Raskin and others of my colleagues at the Institute for Policy Studies with the emotionally and spiritually moving social analysis of the Port Huron Statement, and with the radical community organizing and nonviolent street protests that Tom often led.

I remember him among the SDS gathering to protest in Washington during the Cuban Missile Crisis when in the face of what seemed a quite likely death of millions in a nuclear war, they came in tears and determination to challenge the insanity. Knowing their puny protest could not in that dreadful moment change history, but knowing they needed to speak truth.

I remember him, both excited and ironic, during a tumultuous week in April 1968. President Lyndon Johnson had astonished us all by withdrawing from running for reelection and assigning senior statesman Averell Harriman to negotiate with the Vietnamese governments that LBJ till then had pretended did not exist. And just a few days later, Dr. Martin Luther King was murdered and Black Washington erupted, burning down several major business streets before Johnson sent the U.S. Army to occupy the city.

In the midst of that tumult just a few days later, Tom flew into Washington. He told me that neither Harriman nor anyone at the State Department knew anything useful about the actual human beings, intentions, and policies of the Vietnamese National Liberation Front or the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. (Officially, they had not existed. Militarily, they had been just the enemy, to be destroyed.)

How could Harriman sensibly negotiate without that intimate information and understanding? So Harriman’s office had called Tom, who had been to Hanoi several times and had talked with Vietnamese leaders. Would he come to Washington to brief them?

So he flew into the city. He told me that from the plane he could see the burnt-out business streets, still smoking. He said, “I felt as if the revolution had just happened, and I had been called in to pick up the pieces. I — the poster boy of trouble and treason! I knew it wasn’t so. I knew that Johnson’s defeat was an important defeat for the system, but I knew there was a long long way to go. Much more hard work and deeper change than burning streets, to make the revolution. Still, it was hard to shake the feeling.”

And he laughed, and shook his head — it seemed, to shake off the false triumphal feeling.

SDS National Council meeting, Bloomington, Indiana, 1963. Tom Hayden is at the far left. Photo by C. Clark Kissinger.

And of course he was right. I remember him later in 1968 in Chicago, semi-disguised for fear of being picked out and arrested while he was marshaling the antiwar protests aimed at the Democratic National Convention, asking me and a number of other antiwar Convention delegates to make up a thin line standing between Mayor Daley’s police and the National Guard on the one hand and the Grant Park demonstrators on the other hand, in the hope that we could prevent a bloody police attack on the crowd in the park by putting our “more respectable” bodies in the way.

I remember him facing the rabidly hostile Judge Julius Hoffman at the trial of the Chicago Eight.

I remember him facing the rabidly hostile Judge Julius Hoffman as one of the defendants in the trial of the Chicago Eight, accused by the U.S. government of fomenting riot in Chicago — and calling to ask me to come testify as an eyewitness that the Grant Park demonstrators were planning nonviolent protests, not a violent riot.

I remember him at the end of the trial when the defendants were convicted and sentenced, weeping as he told Judge Hoffman that his chief regret was that the brutal sentence would keep him from having and loving children. (The conviction was reversed because the judge had committed so many travesties on decent judicial behavior and the law; Tom went on to have and to love kids after all.)

I remember him writing and speaking on how the best of the radical Irish tradition, one strand of the thought-weave with which he identified, spoke to justice and to caring for the beloved sacred Earth, and his affirmation of what I had been doing in parallel, drawing on the best of Jewish tradition for the same commitments. The Irish tradition was not just in his head but in his heart; he was a radical version of a people-loving Irish politician.

I remember him just a year and a half ago in a moment of laughing together over a cup of coffee before he took up the struggle once again, speaking at the 50th anniversary gathering to celebrate and renew the Vietnam Peace Movement.

My son David Waskow — Tom’s influence clearly went beyond my own generation — wrote me the morning after Tom’s death, “My favorite line of his: ‘Change is slow, except when it’s fast.’” Both ends of the sentence a powerful reminder to activists who are on the edge of burning out, exhausted and despairing from years and years of effort that feel fruitless.

I imagine him now, not resting in peace but once more taking up the struggle in an ambiguous “Heaven” to win more justice, more peace, more healing in the world.

As we in “the Movement” have come to say, drawing on Latino tradition, “Tom Hayden Presente!” He is not dead, but continues to be alive and present in the lives he touched and taught and moved and changed.

Read more articles by Rabbi Arthur Waskow on The Rag Blog.

[Rabbi Arthur Waskow, Ph.D., founded (1983) and directs The Shalom Center. In 2014 he received the Lifetime Achievement Award as Human Rights Hero from T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights. In 2015 The Forward named him one of the “most inspiring” U.S. Rabbis. He has written 24 books, most recently (with Rabbi Phyllis Berman) Freedom Journeys: The Tale of Exodus & Wilderness Across Millennia and The Loooong Narrow Pharaoh and the Midwives Who Gave Birth to Freedom. Also see his pioneering essay, “Jewish Environmental Ethics: Adam and Adamah,” in the Oxford Handbook of Jewish Ethics (Oxford University Press, 2013). Rabbi Waskow has been arrested about 23 times in protest actions for peace, racial justice, and healing from the climate crisis.]

- Find articles by and about Tom Hayden on The Rag Blog.

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s interviews with Tom Hayden on Rag Radio.

- Read “Thorne Dreyer: As Port Huron Turns 50,” at Tom Hayden’s Democracy Journal, and at Truthout.

Requiem In Pax