Hey, University of Texas Regents! You pinheads are making us mad!

By Mariann G. Wizard / The Rag Blog / February 12, 2009

Austin American-Statesman Outdoor columnist Mike Leggett writes about big mouth bass and white tail deer much of the time; about introducing youngsters to hunting and fishing; and sometimes just about the Texas outdoors in all its glory. I read his week-end column, and often clip it for my brother and nephew, avid fishermen who live near Lake Belton. A few months ago, Leggett was instrumental in exposing a $100,000 pseudo-scientific “study”, funded by the Texas Department of Parks and Wildlife, on whether steel shot kills doves as well as lead shot; carried out by the novel method of having a big old no-limit dove hunt for TDPW employees the day before the season opened for regular folks.

Last Sunday, Leggett took on an even bigger foe, and an even bigger potential boondoggle: the University of Texas Board of Regent’s move to “redevelop” the Brackenridge Tract, 500 acres donated to UT in 1910 by Colonel George W. Brackenridge, a 25-year-plus Regent and philanthropist who, among other things, also donated the land for San Antonio’s enormous Brackenridge Park, all for “purposes of education and research”. Through the years, UT has established graduate student housing on the Tract and leased parts of it, while parts have become de facto City-owned public streets, a low water bridge, public boat dock, and so forth. Spring-fed Deep Eddy pool is part of the Tract.

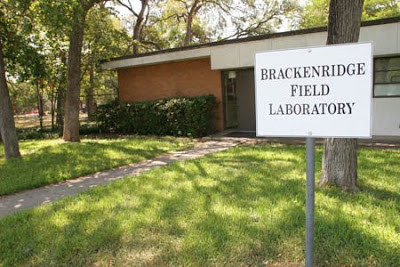

Total acreage of the Tract has thus been reduced to 345 acres. At its heart lies the 88 acre Brackenridge Field Lab (BFL), on what is now prime West Austin riverfront (see map). BFL, established in 1962 at the request of UT’s Botany and Biology departments, is one of the few field research facilities in the nation located in an urban area but within easy reach of a university campus. Its important ongoing projects include fire ant research and the University’s vast entomology (bug) collection. It would not be feasible to relocate the wildlife and plant species living within its borders, and its destruction would be a senseless set-back to basic research in botany and biology.

Frank C. Erwin, Jr., arguably the most ambitious and far-seeing of modern Regents, emphasized Col. Brackenridge’s bottom line in a history of the Tract he presented to the Board in 1973. The Colonel’s bequest had been made “with the request only on [Brackenridge’s] part that [the land] never be disposed of but held permanently for… educational purpose.” In 1921, after Brackenridge’s pipedream of eventually moving UT’s main campus to the Tract was effectively squashed by the Legislature, the Texas Attorney General warned that Regents “should not sell nor attempt to sell any part of the Tract without seeking his prior opinion”. Shortly afterwards, part of the property was leased to the Austin Lions Club for creation of a golf course, a popular use for which it is still employed, although under City of Austin auspices, and the issue lay more-or-less fallow for 40 years — until Erwin’s day.

Repeatedly during the mid-1960s, Regents sought to get more out of the Tract, either in terms of student housing or in terms of income, and in 1967 the Texas Legislature obliged their good friend, Regents Chairman Erwin, by passing Senate Bill 211, authorizing the lease or sale of any portion of the Tract, apparently for any use whatsoever, with funds from such sale (or lease) to go towards land acquisition for expansion of the main “40 acres” campus.

But this didn’t prove immediately necessary, “thanks to the invaluable assistance of President Lyndon B. Johnson”. The University’s “involvement” in the University East and Brackenridge Urban Development Programs, more commonly known as “urban removal”, gutted several lovely, student-affordable, family-friendly, integrated and/or primarily minority neighborhoods east of UT from Speedway to IH 35 and beyond, and south between 21st and 15th Streets (towards Brackenridge Hospital, also donated by the Col.) to make room for Erwin & Co’s megalomaniacal vision of accommodating, on one giga-campus, every high school graduate who could pay the rising tuition costs. Veteran Rag aficionados will recall that Erwin personally led bulldozers to destroy the lovely old oaks along Waller Creek in 1969, in pursuit of his expansionist agenda, calling students who climbed the trees to try to save them “a bunch of dirty nothin’s”. His was not the voice of reason that kept students from being bulldozed, along with the ancient trees, that sad day. Now, where public schools, parks, and neat frame houses with pretty yards once thrived, an endless expanse of University athletic “facilities” and parking lots blends seamlessly with the soulless Capitol-state office complex and still nibbles away at beleaguered East Austin.

In December, 2007, UT Regents approved a motion to retain a master planner to conceptualize redevelopment plans for the west Austin Brackenridge Tract. Their decision has generated considerable heat from various interest groups and constituencies, and even a public hearing or two hosted by impotent City officials, but nothing, so far, that seems likely to slow the development train, unless it might be general economic ruin.

Among all of the many already-valuable, well-utilized, highly-prized resources that have grown up within and around Col. Brackenridge’s gift, Mike Leggett is particularly steamed about the potential loss of BFL, calling it, in language infrequently seen in Austin’s daily paper, “unbridled pinheadism”. In response to an encouraging e-mail from Your Humble Correspondent, he said he’s had a lot of positive responses to the article, and that “we’ll see” if it has any effect.

If the long-lost trees of Waller Creek are any indication, those who value BFL need to speak up now, speak up loud, speak up not just to say “Right on!” to Mike but “Stop the plunder!” to UT’s rulers — and maybe shine up their tree-climbin’ spikes. Otherwise, West Austinites will soon get a taste of the “gentrification” that has already blighted everything within reach of UT’s high-rollers — and everyone in town, including future generations of UT and other students, will be the poorer for it.

(By the way, Leggett’s story mentions that friends have told him he’s been “writing angry” lately, and he’s trying to tone it down. Au contraire, brother, keep it coming!)

Great article Wizard! I wonder how many times some variation of this story has played out across the country? It’s time we started taking photos of trees so our great, great grandchildren will at least get a hint of what they looked like. Yeah, and maybe throw in a few shots of grass, flowers, even weeds…

Response to Mike Leggett’s Statesman story appears in Sunday, 2/15 Statesman Sports section, in Letters. Two letters strongly support preservation of the Field Lab, and one offers a novel mechanism for achieving this goal.

Unfortunately, many progressives don’t read the Sports pages at all, and may not realize that the local daily’s Sports section features its own weekly Letters column. I would hate to see this discussion confined to folks who, like me, read the Sunday paper from stem to stern!

Thanks for the strokes, and I hope you are writing a letter to the Regents as well, letting them know that the Brack Field Lab should be saved!