La Vida Coca /1:

Currents in traditional coca

use in Bolivia and Peru

Although its use continued, coca production had been ‘stripped of its original cultural and social meaning’ by the subjugation of indigenous practice to the whims of European and North American commodity culture.

By Mariann G. Wizard | The Rag Blog | May 9, 2013

Part one of three.

I recently visited Peru and Bolivia for the first time, in the company of intrepid adventurer and fellow former Ragstaffer Richard Lee. It was all his idea, a journey we talked about for a couple of years. Both South American nations are huge, with enormous wild and rugged areas; are rich in geographical, botanical, and cultural wonders; and are repositories of a wealth of ancient and modern histories unfamiliar to many outsiders.

We both like straying off the beaten path. A guide book or “canned” tour is merely a point of reference. While ruins and relics may be spectacular, inspiring, and mysterious, we prefer checking out current life and culture, moving slow, meeting people, and making new friends. Although my trip lasted two months, and Richard’s even longer, it would take years to see all of the “must see” places the tour books extol.

Gradually, with experience, a sharper focus and questions may emerge. While Bolivia and Peru are each unique in hundreds of ways, they have something in common that is quite exotic to North Americans: traditional cultivation and use of coca (Erythroxylon spp). Coca, native to South America, has been used for thousands of years medicinally, ritually, and socially, and grown on several continents. Today Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia produce more than 98% of the world’s coca.

Inca and pre-Incan cultures such as the Moche thought coca was a divine plant and sometimes reserved it for royalty. When the Inca fell to the Conquistadores, the Spanish at first tried to stamp out coca as a pagan practice. But they quickly learned to exploit its energizing qualities. Workers with a ready supply of coca didn’t have to stop for lunch. So coca, monopolized by the conquerors, was “tolerated” for increased productivity, although Catholic missionaries continued to try to stop or limit its spiritual use.

|

| Coca plants were grown by pre-Incan cultures 5000 years ago. These are at Huaca Pucllana, an active archaeological site in the heart of modern Miraflores, Lima, Peru. |

According to Wikipedia, coca was traditionally used

as a stimulant to overcome fatigue, hunger, and thirst… particularly effective against altitude sickness. It also is used as an anesthetic and analgesic [for] pain of headache, rheumatism, wounds and sores, etc. Before stronger anesthetics were available, it also was used for broken bones, childbirth, and during trephining [sic] operations on the skull.

The high calcium content in coca explains why people used it for bone fractures. Because coca constricts blood vessels, it also serves to oppose bleeding, and coca seeds were used for nosebleeds. Indigenous use of coca has also been reported… for malaria, ulcers, asthma, to improve digestion, to guard against bowel laxity, as an aphrodisiac, and [was] credited with improving longevity.[1]

In some coca-using cultures, the herb was specifically linked to sexuality, procreation, and virility.

Richard, an avid horticulturalist, wanted to learn about coca growing. I write professionally about herbal medicines and welcome opportunities to encounter them “in the field.” As we traveled south, and up, to the dizzying Andean altiplano, we started to feed our interests with knowledge.

Coca leaves (hojas) and seeds contain alkaloids and other compounds that exert physical and mental effects when consumed. Coca is intensively cultivated and harvested by hand, usually on well-drained, sunny mountainsides. It prefers somewhat alkaline soil. There are said to be over 250 Erythroxylon species; four are widely grown. Many, if not all, contain cocaine, an alkaloid that is coca’s best-known ingredient.[2] The reported usual cocaine alkaloid content of coca leaf is between 0.1 and 0.8%.

Wikipedia says,

[P]lants thrive best in hot, damp and humid locations, such as the clearings of forests; but the leaves most preferred are obtained in drier areas, on the hillsides. The leaves are gathered from plants varying in age from one and a half to upwards of forty years, but only the new fresh growth is harvested. [Leaves] are… ready for plucking when they break on being bent. The first and most abundant harvest is in March after the rainy season, the second is at the end of June, and the third in October or November.”[3]

|

| Coca is a low-growing deciduous shrub. These plants are thriving in a traditional steeply terraced field. |

Despite its South American origin, coca and its alkaloids have profoundly affected North American and European culture. Again from Wikipedia:

Coca was first introduced to Europe in the 16th century, but did not become popular until the mid-19th century, with the publication of an influential paper… praising its stimulating effects on cognition. This led to [the] invention of coca wine and the first production of pure cocaine.”[4]

In the U.S., cocaine was associated with the Jazz Age and known as a “rich man’s drug.”

But another item originally derived from coca became the one symbol of North America, and specifically the U.S., known around the world: the Coca-Cola® soft drink, brand, and logos. Coke® and other kola (aka cola; Cola vera) drinks originally used coca as a flavoring and energizing ingredient; today’s Coke still uses denatured coca leaves. The Stepan Company (Maywood, NJ), the top legal buyer of Bolivian coca, imports and denatures it. Coke owns Inka Cola®, formerly its main competitor in Peru, and Coke products are ubiquitous in both countries.

|

| Coca Colla energy drink. Photo from Prensa Libre.com. |

“Denaturing” means removing the cocaine. That is sold to Mallinckrodt (St. Louis, MO), the only pharmaceutical manufacturer in the U.S. licensed to purify “coke” for medical use. The only naturally occurring local anesthetic in use today, it was first isolated and purified in 1859. Approved uses include as anesthesia in eye surgery and as a precursor to synthetic prescription and over-the-counter painkillers: novocaine, lidocaine; essentially anything ending with “caine.”

In addition to its medical value, cocaine is an attractive drug of abuse, providing an all-too-fleeting feeling of focused energy and power. Cheap South American coke and its derivative, even cheaper smokeable free-base or “crack” cocaine, flooded U.S. and European markets in the late 1960s, a ruinous flood that, with disco music, peaked in the 80s.

Coke and crack are still used, but methamphetamine is so much cheaper now (as well as heroin, other opiates, and prescription painkillers) that “Bolivian marching powder” has lost market share. The epidemic and resulting intensification of the so-called “war on drugs” left deep scars in many urban communities, put an end to the idyllic dreams of 60s social reformers and much of the U.S. Bill of Rights, bent law enforcement priorities, fed corruption both public and private, and helped fund repressive warfare in more than one foreign nation.

Efforts to control and eradicate coca had begun much earlier. The Convention for Limiting the Manufacture and Regulating the Distribution of Narcotic Drugs, an international drug control treaty, took effect in July 1933. It established two groups of forbidden drugs.

Group I included morphine and its salts, including morphine diacetate (heroin) and preparations made directly from raw or medicinal opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) containing more than 20% morphine; cocaine and its salts, including preparations made from coca leaf containing more than 0.1% cocaine[5], all esters of ecgonine and their salts; dihydrohydrooxycodeinone, dihydrocodeinone, dihydromorphinone, acetyldihydrocodeinone or acetyldemethylodihydrothebaine, dihydromorphine, their esters, and the salts of any of these substances and their esters; morphine-N-oxide, also morphine-N-oxide derivatives and other pentavalent nitrogen morphine derivatives; ecgonine[6] and thebaine and their salts; benzylmorphine and other ethers and salts of morphine, except methylmorphine (codeine); and ethylmorphine and its salts [Italics added].

Group II, more loosely regulated, included methylmorphine (codeine) and ethylmorphine, and their salts.[7]

These rudimentary groups foreshadowed the drug scheduling system still used today. The 1931 Convention was broadened considerably by later treaties and eventually superseded by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, adding cannabis (Cannabis sativa) to the prohibited “narcotics.” International law has been further expanded and amended since. Of course the U.S. has enacted its own drug legislation and has pushed prohibition hard in other nations, especially those it “aids.”

Coca and coca products, used in the Andes for thousands of years and today by farmers, market women, hard-driving taxistas, tourists suffering from altitude sickness, and those with gastric distress, anxiety, high blood pressure, and other medical conditions, was thus prohibited by international law. Although its use continued, coca production had been “stripped of its original cultural and social meaning”[8] by the subjugation of indigenous practice to the whims of European and North American commodity culture.

The history of the U.S. drug war, specifically against coca cultivation in Colombia and Bolivia, is far beyond the reach of this report. It is well summed-up, however, in this assessment:

Attempts to reduce the supply of coca/cocaine oscillate between efforts to eradicate crops on the one hand, and crop substitution on the other… Experts have been unanimous in their condemnation of crop eradication as a viable strategy in isolation for the simple fact that the aggregated coca acreage has not been decreasing because crops have been displaced rather than eradicated.

And not only have such policies failed, but they have been accompanied by substantial ecological damage; virgin areas have been deforested and the environment has been polluted with long-lasting herbicides. But, above all, attempts at eradication have deprived poor peasants and their families of their main source of income.[9]

Crop substitution has had some limited successes. In mountainous Bolivia, coffee (Coffea robusta) was chosen for improvement and propagation. Long scorned as an inferior product, new cultivars, techniques, and training have made Bolivian coffee a star among aficionados.[10] However, unstable prices prevent it from persuading most coca growers to make the switch. Neither eradication nor substitution have ever had the full support of indigenous farmers where they have been tried.

Peru and Bolivia did not accept coca’s narcotic designation, repeatedly protesting in international forums. In 1994, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), the independent, quasi-judicial organ that implements UN drug conventions, said in its Annual Report, “mate de coca… considered harmless and legal in several countries in South America, is an illegal activity under the provisions of both the 1961 Convention and the 1988 Convention, though that was not the intention of the plenipotentiary conferences that adopted those conventions (Italics added).”[11]

But nothing changed legally.

Bolivian coca growers, or cocaleros, began in the mid-1980s to be a political and cultural force. Not coincidentally, in 1985 an energetic young man named Evo Morales was elected general secretary of a local cocalero union; by 1988 he was executive secretary of the Six Federations of the Tropics of Cochabamba.

Around then the Bolivian government, aided by the U.S., began an aerial spraying program to wipe out coca. Morales quickly became a leader among opponents of the program. As a result, he was frequently jailed and, in 1989, beaten nearly to death, dumped unconscious in some bushes and luckily found by colleagues. By 1996, he was president of the Tropics Federation (he retains this office today).[12]

Morales later led a 600 km march from Cochabamba to La Paz. Supporters gave the marchers drink, food, clothes, and shoes. They were greeted with cheers in the capital and the government agreed to negotiate with them. After they went home, the government sent forces to harass them.

According to Morales, in 1997 a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) helicopter strafed farmers with automatic rifle fire, killing five of his supporters. He also recounted being grazed by assassins’ bullets in 2000. But Morales found a growing international audience for his positions, traveling abroad to gain support and to educate people on the differences between coca leaves and cocaine.

He says, “I am not a drug trafficker. I am a coca grower. I cultivate coca leaf, a natural product. I do not refine cocaine, and neither cocaine nor drugs have ever been part of Andean culture.”[13]

After going through several political formations and fighting official suppression, Morales and his compatriots made a deal with a defunct yet still registered party, the Movement for Socialism (MAS). They could take over the party if they would keep its acronym, name, and colors. The former right wing MAS became the left coca activist party, the Movement for Socialism — Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the Peoples. The new MAS is “an indigenous-based political party that calls for nationalization of industry, legalization of the coca leaf… and fairer distribution of… resources.”[14]

At a gathering of farmers in 2005 celebrating MAS’ 10th anniversary, Morales declared the party ready to take power.[15] He was proven correct, winning over 53% of the vote in that year’s Presidential election. Fending off attempts to remove him from office, he was re-elected in a 2009 landslide. Everywhere we went in northwestern Bolivia, graffiti on walls proclaimed, “¡VIVA MAS! ¡VIVA EVO!”[16]

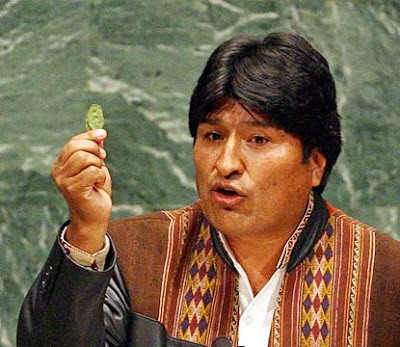

|

| Bolivian President Juan Evo Morales Ayma discussing coca use. Photo from www.parahoreca.com. |

In his first term, in 2008, Morales evicted the DEA from Bolivia. When the U.S. ambassador protested, Evo accused him of conspiring against democracy and encouraging civil unrest, and ordered him out, too. The Bolivian ambassador to the U.S. was expelled in retaliation. Diplomatic relations between the two nations were restored in November, 2011, but have not warmed.

Morales still refuses to allow agents of the DEA into the country.[17] On May 1, 2013, he announced the long-threatened expulsion of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), accusing it of funding his opposition. He also took exception to newly-confirmed U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s recent characterization of the Western Hemisphere as the “backyard” of the U.S., a characterization most Central and South Americans and Canadians, and many U.S. citizens, must find paternalistic, arrogant, ignorant, and typical of the “Ugly Yanqui” we have come to know and despise.[18]

NEXT: Coca’s changing future; the facts as we found them; our quest begins.

[Rag Blog Contributing Editor Mariann G. Wizard, a Sixties radical activist and contributor to The Rag, Austin’s underground newspaper from the 60s and 70s, is a poet, a professional science writer specializing in natural health therapies, and a regular contributor to The Rag Blog. Read more poetry and articles by Mariann G. Wizard on The Rag Blog.]

Footnotes:

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coca

[2] Bieri S, Brachet A, Veuthey JL, Christen P. Cocaine distribution in wild Erythroxylum species. J Ethnopharmacol. Feb. 20, 2006;103(3):439-47.

[3] Wikipedia/Coca, op. cit. Harvest times refer to commercial crops. Fresh hojas are picked and used as needed. Leaves are carefully sun dried for storage and shipment. Coca drops its leaves, like other deciduous plants, but every two-three years; new leaves soon emerge.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Remember, coca leaf material generally has a cocaine level of 0.1-0.8%; so, all products made from coca leaves were covered.

[6] Coca’s alkaloids are all derivatives of ecgonine.

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wikiConvention_for_Limiting_the_Manufacture_and_Regulating_the_Distribution_of_Narcotic_Drugs

[8] Bastos FI, Caiaffa W, Rossi D, Vila M, Malta M. The children of Mama Coca: coca, cocaine and the fate of harm reduction in South America. Int J Drug Policy. Mar. 2007;18(2):99-106. doi:10.1016/j/drugpo.2006.11.017 – local_links.php

[9] Ibid.

[10] Friedman-Rudovsky J. Bolivian buzz: coca farmers switch to coffee beans. Time. Feb. 29, 2012. http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2107750,00.html

[11] Wikipedia/Coca, op. cit.

[12] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evo_Morales#Early_cocalero_activism:_1978.E2.80.931983

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] It must be noted that this area is Morales’ political stronghold. Opposition is centered in the eastern lowland province, Santa Cruz, and its capital of the same name, Bolivia’s most populous city.

[17] Wikipedia/Evo_Morales, op. cit.

[18] Valdez C, Bajak F. Bolivia’s Morales expels USAID for allegedly seeking to undermine government. Associated Press. May 1, 2013. Accessed at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/05/01/bolivia-morales-expels-usaid_n_3193115.html.

This is a great read, a treasure of a narrative. Very fun and informative.