‘Making Waves’ is a significant work, displaying dexterity through penetrating discussions.

By Robert C. Cottrell | The Rag Blog | June 1, 2022

Followers of The Rag Blog should be thoroughly delighted with the release of a vital new volume, Making Waves: The Rag Radio Interviews (Briscoe Center for American History, 2022). Edited by Thorne Dreyer, who delivers a revealing introduction chockful of personal information—more on that shortly–Making Waves contains transcripts of a series of the most meaningful interviews he conducted over the span of Rag Radio’s first decade and a bit longer. Some usual suspects are included—Ronnie Dugger, Eddie Wilson, Jim Hightower, and Kaye Northcott spring to mind—but there are others, some of whom I couldn’t have predicted—who also enrich the pages of this new book, while demonstrating the breadth and depth of Rag Radio and its host’s interests. And make no mistake about that. Making Waves is a significant work, displaying dexterity through penetrating discussions involving politics, journalism, and writing, naturally, but also American culture in general, including music, art, and sculpture. Its sweep goes far beyond the Movement and counterculture that Dreyer has for so long been associated with, although those are hardly ignored. In the process, this book makes a major contribution, in this reader’s estimation, to American letters, not simply the field of journalism. But not to worry, readers. Dreyer’s new book isn’t heavy altogether, containing, much like his on-air commentary and patter, pathos, humor, intriguing asides, and any number of irreverent moments.

‘Making Waves’ continues a pattern of enriching the historical record, beyond the academic world or Establishment journalism.

Making Waves does something else as well, which should interest fans of The Rag Blog. It continues a pattern of enriching the historical record, beyond the academic world or Establishment journalism, initiated some time ago by Austin residents who were important actors in the same Movement, the counterculture, or both. Three decades ago, Daryl Janes presented a collection of interviews, No Apologies: Texas Radicals Celebrate the ‘60s (Eakin Press, 1992), which included remembrances from Robert Pardun, Mariann Wizard, Dick Reavis, Jim Simons, and Terry DuBose, among various Austinites, in addition to photos by and one of Alan Pogue. Almost a decade later, Pardun, in Prairie Radical: A Journey Through the Sixties (Shire Press, 2001), depicted the early phases of SDS activism, particularly in Texas’ capital city. Through Witness for Justice: The Documentary Photographs of Alan Pogue (University of Chicago Press, 2007) employed the lens of photojournalism to capture protest activity, scenes of the counterculture, and social ailments in Texas, other parts of the Southwest, Latin America, the Near East, and the Middle East. Simons soon offered his life story and involvement in legal crusades through his autobiographical Molly Chronicles: Serotonin Serenade (Plain View Press, 2007). Another self-rendering, Borderlands Boy: Love, War and Peace in the Atomic Age (Sunstone Press, 2019), by Ken Carpenter, highlighted draft resistance and the quest for gay liberation.

Purchase Making Waves: The Rag Radio Interviews at the Briscoe Center for American History.

Last summer, Alice Embree published her highly insightful, significant memoir, Voice Lessons (Briscoe Center for American History, 2021), offering a much-needed woman’s perspective of the decidedly left-of-center people’s campaigns of the past sixty years. Pogue will soon release his exploration, through photographic images, of “how people created their own alternative institutions during the 70s.” Now, Dreyer delivers his own captivating collection, Making Waves, which is probably as close to an autobiography as the Movement veteran is likely to produce. This is because something of Dreyer’s personal history, also sprinkled in two recently published works, is included in this forthcoming book. Those books, of course, are Celebrating the Rag: Austin’s Iconic Underground Newspaper (New Journalism Project, 2016, ed. Thorne Dreyer, Alice Embree, and Richard Croxdale) and Exploring Space City!: Houston’s Historic Underground Newspaper (New Journalism Project, 2021, ed. Thorne Dreyer, Alice Embree, Cam Duncan, and Sherwood Bishop).

Each of these three invaluable books contains not only statements by Dreyer but tidbits regarding his life story. The fullest account appears in the introduction to Making Waves, which follows a fine preface by the historian Don Carleton, who is also executive director of the University of Texas’ Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, home to the Rag Radio archive. Opening with a dramatic flourish, Dreyer recalls the twin Klan bombings in 1970 of the Pacifica radio station KPFT-FM, where he hosted a program, The Briarpatch, in his hometown of Houston later in the decade. Forty years later, he found himself hosting and producing Rag Radio, a weekly, syndicated program found on KOOP-FM, a non-profit community station in Austin. Soon to experience its thirteenth anniversary, the hour-long show presents interviews generally conducted by Dreyer with activists, artists, musicians, journalists, academics, writers, and other figures, many possessing national or even international renown, willing to explore life stories or seminal moments of interest to the KOOP-FM staff and the station’s legion of fans. That is in keeping with the KOOP-FM’s mission: “To engage, connect, and enrich the whole community, including the underserved, through creating diverse, quality, educational music and news programming.”

Rag Radio draws from the famed underground newspaper, The Rag.

As Dreyer recounts in his introduction, Rag Radio draws from the famed underground newspaper, The Rag, that he, Embree, Pogue, and several others still involved in local and national progressive issues helped to sustain for some or all of its eleven-year existence (1966-1977). Among the first and most influential of the nation’s underground publications, The Rag provided a forum for Austin’s New Left, antiwar, civil rights, and women’s movement, and stood as a beacon for the then much smaller city’s thriving counterculture. In many ways, as Dreyer notes, Rag Radio maintains that unique determination to blend the personal and the political, albeit with something of a more consistent feminist twist.

Along with providing a quick encapsulation of the history of The Rag and Rag Radio, Dreyer also offers biographical information about his parents, the journalist and creative writing instructor Martin Dreyer and the painter-muralist Margaret Webb Dreyer, and growing up in the eccentric Montrose community perched in downtown Houston. He discusses the love of art he shared with his family and the progressive politics the three displayed regarding the Vietnam War and human rights. His pre-Austin years included an abbreviated “art career” and acting stints that took him to New York City for a spell. But he became immediately “smitten” with “Nirvana in the Hills,” as he thought of Austin. A brief enrollment at the University of Texas was followed by more consequential involvement with Austin’s early SDS, street theater, civil rights engagement, and antiwar activism.

In 1966, Dreyer helped to found The Rag, for which he served as the original “Funnel,” helping to orchestrate a publication that strove to model the participatory democracy the New Left then propounded. Having moved to New York City, he helped to edit Liberation News Service, which provided stories to underground papers around the country and beyond. Returning to Houston in 1969, Dreyer was a cofounder of Space City!, Houston’s foremost underground paper, assisted George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign, became a political consultant, contributed to Texas Monthly, ran a public relations firm, helped to manage Mums, a jazz club in downtown Houston, managed a jazz singer, and got involved with bookselling operations.

That personal info, perhaps coupled with an interview I conducted with Dreyer on Rag Radio last summer, provides the nucleus for a mini-bio of Dreyer. But his lifework, through the essays and articles he wrote for both the underground and the above-ground press, offers still more facets about him. So do the often-scintillating interviews Dreyer has conducted for Rag Radio, twenty-one of the most telling of which are transcribed in Making Waves. Hardly a simply compilation of such interviews, this book instead offers running commentary between the host and his guests, whom he has smartly divided into storytellers, visual artists, impresarios, music makers, politicians, New Lefties, and rights fighters. Even its title is on point, for the individuals included have all made and are often continuing to make a difference in the lives of their communities, both near and far.

They underscore Dreyer’s significance as a foremost

intellectual and activist.

Clearly, these segmentations have not been randomly chosen but instead evoke various aspects of Dreyer’s life and times, certainly what has driven and sustained him during good and bad times over six decades of involvement at the cutting edge of Austin’s—and this country’s–progressive political and cultural currents. They underscore his significance as a foremost intellectual and activist. Making Waves amounts to a major contribution to American letters and will likely be consulted over and over again. I felt this still more emphatically during my second full read through this work, which again invoked a series of thoughts regarding the necessity of commitment, engagement, integrity, and a willingness to persevere through the tough moments and hard knocks that movements, artistry, and individuals inevitably endure. There’s also the sheer joy of remembrances of good friends, shared moments, victories, even setbacks, and a continued seeking of the holy grail, no matter how quixotic that can seem. The lively exchanges, many with individuals close to Dreyer personally or in spirit, exude warmth, concern, commitment, dedication, and yes, pure delight in finding solidarity among kindred souls.

Storytellers

Making Waves’ storytellers include the nation’s onetime leading broadcaster for CBS News, Dan Rather, and his daughter Robin, an environmentalist; the journalists Bill Minutaglio and Kaye Northcott; the founding editor and later publisher of The Texas Observer, Ronnie Dugger; The Realist’s Paul Krassner; the screenwriter Al Reinert; and author Harry Hurt III. The interview with the Rathers focuses on Dan’s splashing onto the scene amid Hurricane Carla’s hurtling close to Galveston in 1961, Robin and Thorne’s sharing of having been “journalism brats,” Dan’s recollections of Martin Dreyer, idealism, Austin’s “magical” makeup, Austin’s being “progressive only by Texas standards,” and the need for visionaries. Dan concludes the talk by observing, “Hearts can inspire other hearts with their fire.” Insisting “not all is lost” due to “We the People,” he wonders, nevertheless, “whether we can muster the will and whether we will put our own hearts and fire and thus inspire others.”

Spinning tales of the populist journalist Molly Ivins, her colleagues Minutaglio and Northcott talk about her being “an anecdote machine,” growing up a “Clydesdale among Thoroughbreds,” prominence as one of the nation’s most revered columnists, battle with breast cancer, ambition, and acting as a trailblazer for women. They also point to Ivins’s friendships with Texas political movers-and-shakers like Ann Richards, Dave Richards, and Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock, who, on being “hip-checked” to the floor by her, said, “Son of a bitch, I love that Molly Ivins.” Northcott reflects, “I think she’s a major presence who will be remembered.”

Dugger relates dealings with Lyndon Baines Johnson, whom he accused of seeking ‘to bribe’ him.

Having first met Dugger when he published the Texas Observer, Dreyer introduces him as the mentor of a host of progressive journalists like Ivins, Northcott, Willie Morris, Lawrence Goodwyn, and Jim Hightower, among others. Recalling being alienated by the postwar red scare, Dugger connected with progressive Democrats, including Frankie Randolph, a Houston heiress and liberal activist, willing to afford him complete control of the new publication. Dugger relates dealings with Lyndon Baines Johnson, whom he accused of seeking “to bribe” him, “basically,” by promising to greatly increase the Observer’s subscription level in return for lending political support. Regarding LBJ, Dugger acknowledges that as president he was genuinely determined to help Latinos and Blacks. Dugger, who wrote a well-received biography of Johnson, also credits his presidency as being “the most progressive” on domestic affairs following FDR’s tenure in the Oval Office. The Vietnam War “ruined” that aspect of the Johnson White House, as well as the country where the conflict was largely waged. The conversation ends with both parties agreeing on the need for a larger public sector.

A godfather of underground journalism, Paul Krassner had frequently crossed paths with his host. The Realist, an irreverent magazine that began during the heyday of the beats—1958—drew on “the anti-censorship tradition” laid out by Izzy Stone and George Seldes, who ran their own progressive newsletters rooted in the ideals of the Old Left. But The Realist was influenced by satirical aspirations with its originator striving for “a Mad magazine for grown-ups.” When the counterculture emerged, Krassner was on the scene while also participating in political activities, in addition to serving as an inspiration for the Fugs and the Yippies alike. Among Krassner’s other accomplishments was his editing of the autobiography of the famed social comedian Lenny Bruce, one of the 60s’ antiheroes hounded by narrow-minded sorts, uptight cops, and Javert-like prosecutors.

A onetime colleague of Dreyer’s with Texas Monthly, Al Reinert reflects on the publication and the fact that the Lone Star State is “a great place to be a journalist.” Texas, after all, “grows these incredible characters all the time. And they’re always doing this crazy stuff,” Reinert indicates. He was also involved in operations at KPFT, where, his initial “day on the payroll [it] got blown up the first time.” The station was viewed “by Texas standards” to be “too radical at the time.” The explosions, Reinert remembers, actually made it “much easier to raise money” with the staff intoning, “Put us back on the air!” Reinert also served as press secretary for Congressman Charlie Wilson, the “larger-than-life” character portrayed by Tom Hanks in a major Hollywood film. Reinert got involved in making documentaries, including the award-winning For All Mankind that covered the moon landings, and An Unreal Dream about Michael Morton, who was incarcerated in Texas for a quarter-of-a-century for a murder he didn’t commit. As Dreyer notes that Austin has become an important cinematic center, Reinert indicates, “Texas, in general-and Austin, specifically-is a culture that encourages you to be who you are. No matter how nutty you are.” Plus, “the people are so much nicer . . . so much easier to work with,” Reinert offers. As for Austin, he refers to it as “the Greenwich Village of Texas for a hundred years.”

Harvard graduate and son of a Texas oilman, Harry Hurt III, former Texas Monthly senior editor, New York Times columnist, and Newsweek correspondent, wrote a scathing early biography of Donald Trump. In an interview conducted less than two months before the ill-fated 2016 presidential election, Hurt states, “I know the person who most realizes on this earth that Donald Trump is not fit to be president . . . and not fit to actually do the job . . . is Donald J. Trump himself.” Turning to Texas Monthly, Hurt calls it “a homegrown, Texas-born magazine that had national reach” but had devolved badly, before segueing back to Trump. When Dreyer mentions that some people say “he’ll shake things up,” Hurt agrees. “He will. So will a bull in a china shop.”

Visual Artists

Section two of Making Waves covers the visual artists through interviews with the Houston curator-art historian Pete Gershon, architectural installer Margo Sawyer, Texas Cosmic Cowboy originator Bob “Daddy-O” Wade, and cultural historian Jason Mellard. Sharing an interest in the subject of Gerson’s recent book, Collision: The Contemporary Art Scene in Houston, 1972-1985, the two discuss what Dreyer denotes as “a collision!” that “included fistfights and food fights and floods.” To that, Gershon adds, “Fires.” Houston, Dreyer suggests, “had always been a pretty lively art center.” But the period Gershon explores in his book “was also a rollicking time politically” with many of the artists proving to be political as well. The museum director-artist Jim Harithas, for instance, “was politically radical,” according to Dreyer.

UT Professor in Fine Art Margo Sawyer, who creates “sacred space” out of fusing of art and architecture, discusses employing “color in terms of collisions, of unexpected meetings in the ways that colors can collide and have a conversation.” She insists on the importance of the arts in the field of education, urging that STEAM—“science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics”–not STEM, be the focus. Politically engaged, she “brought the Guerrilla Girls to campus,” the anonymous group of gorilla-masked women battling against sexism and racism inside the world of art.

The dual interview with Bob Wade and Jason Mellard begins with a reference to the historian’s book, Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texas in Popular Culture, which lumps Wade in with the likes of “Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Eddie Wilson and Doug Sahm” as Cosmic Cowboys. Wade reflects on his studies through UT’s art department, his classical training, and the influence of off-beat artists from the Texas Ranger, including Gilbert Shelton, and Jim Franklin, in addition to his graduate studies at the University of California at Berkeley. Eventually a college professor, Wade ultimately opted to focus completely on his own artwork and to spread the gospel of Texas, as through his devising of forty-foot-tall boots initially viewed in Washington, D.C. and a forty-foot-long iguana on the roof of the Lone Star Café in New York City.

Impresarios

Making Waves presents a pair of “Impresarios”: Eddie Wilson of Armadillo World Headquarters’ fame and Margaret Moser, the groupie turned renowned music producer and acclaimed rock journalist. Armadillo founder Wilson and Dreyer explore the Austin musical scene, particularly during the heyday of that famed musical venue, the 1970s. They share thoughts about a little-known musician from New Jersey during the early part of that decade, whom Kenneth Threadgill, another music trailblazer, considered “as nervous as a coon trying to pass a peach pit.” However, following a “thunderous Thursday performance” by a young Bruce Springsteen and a “warm-up band,” sales for the next two nights mushroomed. As Wilson sees it, “The audience and the food”—including shrimp enchiladas—made the Armadillo. Wilson, who had “managed” the unmanageable Shiva’s Headband, “the hippie rock and roll band,” talks about discovering the Old National Guard armory at 505 Barton Spring Road, where he set up the spacious music hall and outdoor beer garden that ushered in countless memorable presentations. Bookings included Wilson’s “psychedelic hero,” Timothy Leary, and Leary’s old LSD-experimenting sidekick at Harvard, the former Professor Richard Alpert turned Baba Ram Dass. The Armadillo itself became, according to Wilson, “the largest petri dish in the world.” Continuing their talk, Dreyer and Wilson bring up the Vulcan Gas Company, the Armadillo’s countercultural precursor, and frequent guest Mance Lipscomb, the terrific blues musician. They also discuss Gilbert Shelton from The Rag with his comic (or, in the parlance of the counterculture, comix) strip, The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, along with Threadgill and his appropriately named old eatery and musical hangout, Threadgill’s, which Wilson later purchased and ran.

Next up is another Austin legend, Margaret Moser, who joins Dreyer in a fond recollection of performers such as “the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Eric Johnson . . . . Townes Van Zandt, Willie Nelson” and Lucinda Williams. They also talk about Asleep at the Wheel, “Joe Ely . . . Ray Benson and . . . Doug Sahm.” In Moser’s estimation, such musicians were “not just Austin oriented but have risen above and beyond and made Texas music something that everybody listens to around the world.” She brings up Greezy Wheels, Roky Erickson of Thirteen Floor Elevators, Stephen Burton, and Steven Fromholz, and discusses her directing of the Austin Music Awards during South by Southwest. Urged by Dreyer, Moser also reminisces about her involvement with the Austin Sun, a short-lived journalistic venture led by New Left veterans Jeff Nightbyrd (Shero) and Michael Eakin where she began her writing career.

Hot on the heels of transcripts of the two impresarios, Making Waves presents exchanges with “Music Makers”: “psychedelic folk rock” and outlaw country guitarist Bill Kirchen, composer David Amram, and Ed Sanders of the Fugs. Leading off their conversation, Dreyer quotes from a Washington Post reporter who indicated that the manufacturers of Fender Telecasters should “cut Bill Kirchen a big fat check.” Kirchen talks about his high school days shared with the fellow who became Iggy Pop, growing up in Ann Arbor, and seeing the MC5 at an early point. A key figure in Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, Kirchen thinks the band helped “to turn on a whole generation of people to country music, to hard-core, blood-and-guts country and western swing.” At the Armadillo, Commander Cody performed alongside Greezy Wheels and, like Maria Muldaur, appeared at the “Last Dance at the ‘Dillo.” Encouraged by Dreyer, Kirchen conveys appreciation for Gilbert Shelton and Jim Franklin, the artist who drew “the surrealistic armadillo” found on many Rag covers and also did the cover for a Commander Cody’s album.

Referred to as the ‘Renaissance Man of American Music,’ Amram was present at seminal beat events.

Referred to as the “Renaissance Man of American Music,” Amram was present at seminal beat events, produced cinematic musical scores, and worked with musicians ranging from Leonard Bernstein to Dizzy Gillespie. A frequent visitor to Austin, Amram expresses love for Texas, which he first visited during the 1940s. Performers from all kinds of musical genres then “seemed to appreciate everybody else’s work and efforts,” Amram relates. That was certainly true in Austin, and “it’s still that way . . . today,” he continues. Offering gentle advice, Amram urges, “Work harder than is expected, realize that if you give more than you receive, you’re not an imbecile or a business failure, you’re simply doing what the highest level of a human being can do, which is to make a contribution.” Joyfully, he adds, “I’m living proof of that because I have so much fun doing what I’m doing, including being here at a radio station that’s cooperatively run.” Dreyer and his guest, who knew Cisco Houston, Pete Seeger, and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, before encountering Woody Guthrie, spend a fair amount of time conversing about the great folk singer-writer. At one point a “cut-rate ambassador of good cheer” for the State Department, Amram went with Gillespie, Stan Getz, and Earl Hines, to Havana where they performed Afro-Cuban music. He also talks about meeting Jack Kerouac, who, he recalls, “loved Mozart and Shakespeare and jazz equally, as I did.” Singing Kerouac’s praises, Amram claims, “He was the engine that pulled and continues to pull the train, and like Woody Guthrie and Will Rogers and so many other people, make us see ourselves and treasure the place that we live. Treasure the blessings of our own country and all the people who live here and realize that we live in a global culture and we can all somehow join hands in some way, and that starts out by digging yourself and your own story.” Finally, Dreyer’s guest mentions the impending world premiere of a film, David Amram: The First 80 Years, with music to be performed by “all these wonderful people—Henry Butler and Paquita la del Barrio, Peter Seeger . . . Tom Paxton . . . Peter Yarrow,” to name a few.

The “poet, singer, author, publisher, environmentalist, and political activist” Ed Sanders is a natural fit for Making Waves. Best-selling author of The Family, which presents the story of Charles Manson and his deadly cult, Sanders also was a founder of the East Village Other, an underground contemporary of The Rag; the Peace Eye Bookstore in New York City’s Lower East Side; the Fugs; and the Yippies. Sanders is another figure who, as Dreyer puts it, “straddled the beatnik and hippie” eras. Harking back to 1966, the year both the East Village Other and The Rag appeared, Dreyer declares, “What a long strange trip it’s been,” and Sanders acknowledges, “We thought that things were going to change greatly in America. . . . We were wrong.” When Dreyer admits, “What we didn’t do is build anything that was really lasting,” Sanders concludes, “We lost the battle of the textbooks.” Returning to a discussion of the beats, Sanders agrees with Dreyer’s assessment that their emergence involved “kind of a convergence of poetry and jazz.” He was close to Allen Ginsberg, Sanders reveals, with the two speaking before the great poet passed. As for the Fugs, Sanders states, “Hey, we were a bunch of testosterone-crazed young men mainly from the Midwest and West and we have to be forgiven” for their less than politically correct lyrics. At the end of their talk, Dreyer offers, “One of my greatest regrets is that you guys were not able to levitate the Pentagon.” Sanders responds, “Well, we did it. We raised it, but we forgot to rotate it.” Nevertheless, the Battle of the Pentagon—both Dreyer and Sanders were present throughout—“was a remarkable set of acts.”

Politicians

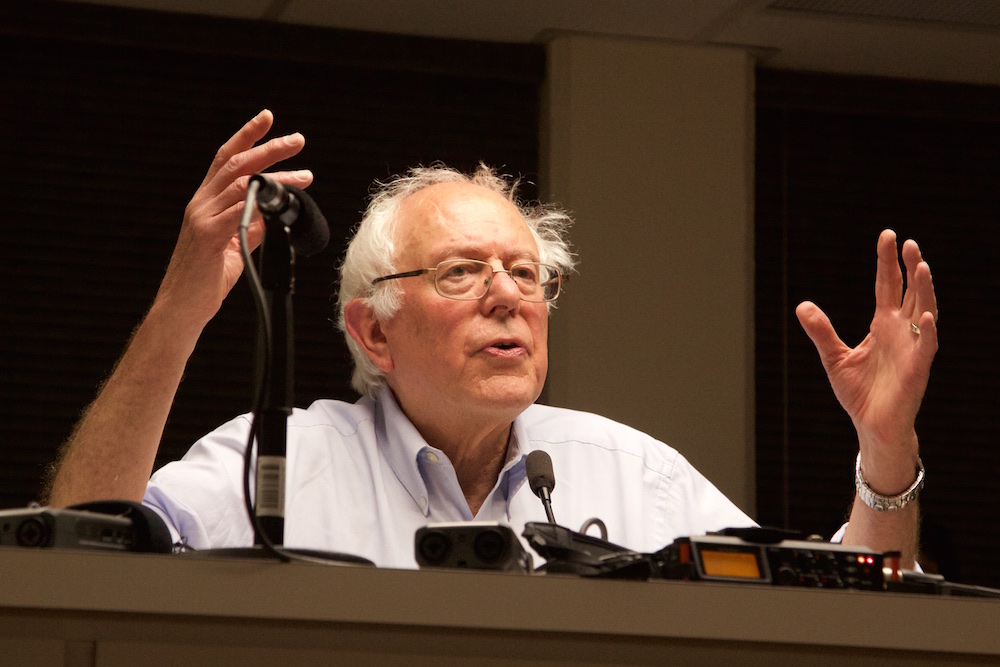

US Sen. Bernie Sanders in Austin. Photo by Alan Pogue. Photo appears in Making Waves: The Rag Radio Interviews, published by the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

In his section titled “Politicians,” Dreyer presents interviews with a pair of the most remarkable political figures of the past half-century: Vermont Senator and, later, two-time presidential aspirant Bernie Sanders, one of the few self-proclaimed democratic socialists ever to sit in Congress, and Jim Hightower, the former Commissioner of Agriculture of Texas and a genuine populist. Dreyer points to the fact that prior to his time in the Senate, Sanders served as mayor of Burlington and then in the US House of Representatives. Sanders discusses an array of problems confronting the nation, including “grotesque” income and wealth gaps, and the Republicans’ readiness to slice “Social Security, Medicare . . . Medicaid—and education” while ladling “tax breaks to the rich.” Referring to Jim Hightower, Sanders calls him “an old and dear friend of mine” and says “you should be very proud of your local agitator in Austin” who believes in the necessity of grassroots activity. Sanders warns of the impact of Citizens United, the US Supreme Court decision tossing aside many curbs on campaign financing; the determination of the reactionary Koch brothers to destroy the welfare state; and the Republican readiness to suppress voting and conduct “outrageous gerrymandering.”

Hightower declares that the Occupy Movement ‘ignited the imagination of the American people.’

A frequent guest on Rag Radio, the “progressive populist commentator” and political activist Jim Hightower served for two terms as state ag commissioner. A one-time editor of the Texas Observer, Hightower also puts out the Hightower Lowdown, a newsletter with nearly 150,000 patrons; writes a national newspaper column; and delivers syndicated radio commentary. The transcript included in Making Waves is drawn from Dreyer’s initial interview with Hightower for Rag Radio. Dreyer’s introduction contains a quote from Molly Ivins: “If Will Rogers and Mother Jones had a baby, Jim Hightower would be that rambunctious child—mad as hell, with a sense of humor.” Calling his guest “perhaps the best-known progressive populist thinker in this country,” Dreyer asks him to define “populist.” Agreeing with Dreyer, Hightower indicates that “it definitely has class and it is very, very progressive.” It involves “confronting money and power in our society and realizing that too few people control too much of the money and power and they’re using that control to get more for themselves at our expense.” That was precisely what was occurring in the United States presently, Hightower insists. In that vein, the Occupy movement involved “the inequality, the disrespect, the knocking down of the middle class.” Deeming it “extraordinarily important,” Hightower declares that “it ignited the imagination of the American people.”

New Lefties

“New Lefties” presents dialogues between Dreyer and his guests: Tom Hayden, Bernardine Dohrn, and Bill Ayers, all former national officers in the leading New Left organization of the 1960s, Students for a Democratic Society. The lead architect of SDS’s seminal manifesto, The Port Huron Statement with its propounding of the ideal of participatory democracy, Hayden freedom rode in the Deep South, where he was beaten, served as a community organizer in Newark through SDS’s Economic Research and Action Project, became a leader of the antiwar movement, and was one of the individuals—the so-called Chicago Eight–charged with conspiring to spark riots in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic Party National Convention. Later, along with his then wife Jane Fonda, Hayden helped to found the Campaign for Economic Democracy and was a longtime state legislator in California. SDS-Movement compatriots Dreyer and Hayden exchange pleasantries at the beginning of their talk. Hayden declares, “I admire what you’ve done over all the decades; you’re like one of the old trees in the forest of the ‘60s.” Returning the compliment, Dreyer states, “It’s amazing to me that you’ve continued to do such important work consistently throughout the years. You’ve been an inspiration to all of us.” Referring to The Port Huron Statement, Hayden wonders if such a document can be replicated. “These kind(s) of crazy inspired visionary documents,” he says, “often come from the young and liberated and innocent.” But it remains “a little uncanny how the words . . . echo today.” Viewing Occupy Wall Street’s manifesto optimistically, Hayden sees it as calling for “transparent participatory democracy. . . . I think it’s very hopeful and it’s become a universal consensus that they’ve changed the dialogue to income inequality and poverty.”

Dohrn and Ayers gravitated from their involvement in top SDS circles to leadership of the group that spun off from that New Left organization, Weatherman, which eventually came to be known as the Weather Underground. After heading underground themselves in 1970, they resurfaced nine years later. Both returned to academia, Dohrn as a law professor and head of Northwestern’s Children and Family Justice Center and Ayers as a well-regarded professor of education at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The interview opens with a discussion regarding the controversy during the 2008 presidential campaign that swirled around the fact that Dohrn and Ayers, partners and comrades for nearly five decades, lived in Hyde Park, a tony district in Chicago, as did Democratic Party candidate Barack Obama, a casual acquaintance “around the neighborhood.” The three New Left veterans agree with a characterization of Obama as an “ambitious,” moderate politician, hardly the “secret socialist . . . secret terrorist . . . secret Muslim” that Republican vice-presidential nominee Sarah Palin portrayed him as being. Dohrn points to Obama’s work as a community organizer, while Ayers suggests that his election was “nowhere near a fatal blow, or final blow” regarding white supremacy. Ayers emphasizes that “all the great moves forward in the last hundred years came from fire from below, movements on the ground.” Later, they focus on two key areas Dohrn and Ayers have long been involved with: criminal justice and public education. While Dohrn underscores the importance of “treating everyone as if they have tremendous possibility,” Ayers warns of the “really profound class and race division system” afflicting American schools.

Rights Fighters

The final section of Making Waves features “Rights Fighters.” The radiation oncologist Leon B. McNealy was a civil rights activist while attending high school and the University of Texas. The Texas scientist-attorney Frances “Poppy” Northcutt undertook a career that included high-level engagement with the nation’s space program and women’s rights. The American historian and activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is a leading feminist who became an important scholar able to offer her distinct version of “people’s history.” First engaged in the civil rights movement as a high school student in Houston, McNealy participated in sit-ins battling segregation in Austin businesses, went head-to-head with President Logan Wilson regarding Jim Crow practices at UT, and helped lead the “stand-ins” designed to integrate movie theaters on the Drag, across from the campus. McNealy, whose interview was peppered with humor, also wrote satirical pieces for The Texas Ranger. McNealy recalls support from older figures like St. John Garwood, who sat on the state supreme court; the famed humorist and civil libertarian John Henry Faulk; the politically-prominent Mavericks, who included former members of Congress and the Texas House; the historian Walter Prescott Webb, who served as president of the American Historical Association; and Fred Gipson, author of Old Yeller. Supportive too was Huston-Tillotson, the largely black college based in Austin. Singling out Chandler Davidson, Houston Wade, and Casey Hayden, McNealy declares, “I’m in awe of their brilliance.”

The mathematician and engineer Poppy Northcutt, who later turned to the legal profession, assisted with NASA’s Mission Control but was also a leader in both local and national branches of the women’s movement. As Dreyer notes, Houston, where NASA was effectively based, “was kind of the epicenter of the women’s movement in the country.” Accepting that analysis, Northcutt says, “We had a very, very strong women’s rights movement in Houston in particular, and in Texas in general.” Key figures included Houston mayor Kathy Whitmire; Sissy Farenthold, an early gubernatorial candidate; and Ann Richards, who actually ascended to the governor’s mansion in 1991. As Northcutt recalls, “Houston was very progressive,” while Texas became “the fifth state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.” Additionally, “we have our own state Equal Rights Amendment . . . that was passed overwhelmingly.” Feminists had “full-time legislative lobbyists . . . and we passed equal credit laws.” Other distinctions for Northcutt involved her becoming perhaps the first women’s advocate, working for the City of Houston, in the nation, and serving as the initial prosecutor there handling domestic violence cases. She also helped to organize a series of feminist events such as the National Women’s Conference held in Houston in 1977.

‘Outlaw woman’ Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz became a leader of

second-wave feminism.

“Outlaw woman” Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz became a leader of second-wave feminism, helping to found Boston-rooted Cell 16, which celebrated celibacy, separateness from men, and self-defense, and to publish No More Fun and Games, the initial women’s liberation journal. Another returnee to university life, she became a historian and professor of Native American Studies at California State University, Hayward, as well as author of An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Noting that she has been tagged an “engaged intellectual,” Dreyer asks why Dunbar-Ortiz views herself as an “outlaw.” She replies, “At one level I consider myself a Marxist, feminist, intellectual, academic historian, specializing especially in Indigenous studies.” But she also recalls her roots, particularly her hard scrabble Oklahoma ones, with her grandfather having been a member of both the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World, and her father spinning tales of literal outlaws. As for being “an outlaw woman,” Dunbar-Ortiz believes that is “what I kind of became on the left. In the old English sense of the word—because an outlaw in England was someone who literally was outside the law. They had no rights whatsoever. . . . That’s kind of how I saw myself.” Over time, she gravitated from involvement with the antiwar and antiracist movements, as well as supporting farm workers, to becoming “angry about the status of women within the Left.” Seeking to “end on a positive note,” Dunbar-Ortiz contends, “The younger generation is finding ways to create another world that I find very exciting.” She points to young Native Americans who were intending to become professors. “That is very unusual,” she says. “It’s going to change the universities, their presence.”

Although spanning nearly 400 pages, Making Waves never seems lengthy. But initially, my first impression was that the book, although indisputably impressive, did lack something: a meet-and-greet between Dreyer and another member of the Movement in Austin. But having reflected on that more fully, I’m uncertain how he would have singled out such a figure. Embree? Pogue? Nightbyrd? Or yet another key actor? And in the end, Making Waves is not simply about the Movement in Austin or even Austin itself. Its reach–and what it accomplishes–is considerably larger than that.

[Robert C. Cottrell, professor of history and American studies at Cal State Chico, is the author of All-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today, Sex, Drugs, and Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Rise of America’s 1960s counterculture, and Izzy: A Biography of I.F. Stone.]

- Read articles by Robert Cottrell on The Rag Blog.

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Robert Cottrell and Robert Cotrell’s Rag Radio birthday interview of Thorne Dreyer.