He was always fiercely independent and intelligent.

By Robert C. Cottrell | The Rag Blog | March 24, 2022

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s two classic Rag Radio interviews with Todd Gitlin from July 19, 2013, and August 16, 2013. Listen anytime here and here.

- Read Katharine Q. Seelye’s Todd Gitlin obituary in The New York Times, here.

There are undoubtedly those in The Rag Blog community who knew Todd Gitlin far more intimately than I. My direct dealings with him were limited to a small number of occasions. The first involved his response to a query of mine regarding the radical journalist I.F. Stone, about whom I was working on a dissertation. To my delight, Gitlin was one of several luminaries who quickly fired off a lengthy letter to me, then a grad student, in that seemingly long-ago time before emails. He indicated that Izzy, whom he knew, had agreed to deliver a talk on Vietnam to the SDS National Council convening in December 1964. Stone’s address, as Gitlin remembered, proved “eloquent and stirring.” It “therefore, probably played a part in helping generate the enthusiasm for” a scheduled antiwar gathering in Washington, D.C., the next spring, which proved catalytic for the Movement.

Gitlin also recalled being one of several in the early SDS leadership who “devotedly read” I.F. Stone’s Weekly. To Gitlin, Izzy “was always an exemplar of intellectual and political integrity, one of the few of his generation we felt had not been fatally compromised by either Stalinism or inflexible anti-Communism.” Gitlin pointed as well to the great peace advocate A.J. Muste and the pacifist David Dellinger as “the only others of [Izzy’s] generation who played similar parts — respectful, admirable, and critical at the same time.” Others often mention the venerable Norman Thomas, the longtime leader of the Socialist Party of America, as an admirable veteran of the Old Left; Gitlin likely would have too had Thomas come to mind.

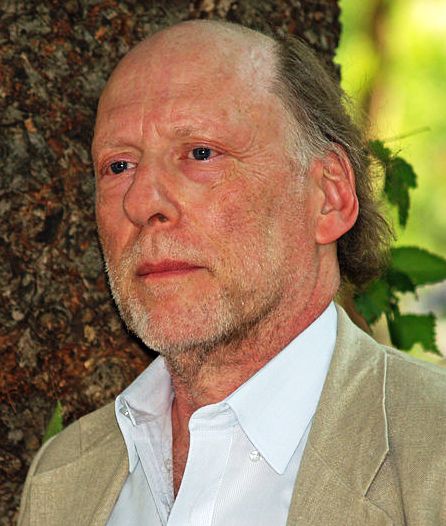

Gitlin eloquently spoke before a sizable, enthusiastic crowd about

his days in the Movement.

A few years later, Gitlin, after an exchange of correspondence and phone calls, accepted my invitation to come to the campus where I was teaching, California State University, Chico, in Northern California, to serve as a Distinguished Visiting Professor for a brief stint. Following my too abbreviated introduction, Gitlin eloquently spoke before a sizable, enthusiastic crowd about his days in the Movement, including his tenure as SDS president and fostering of the New Left organization’s ERAP (Economic Research and Action Project) venture. He talked about the state of the American left as of the end of 1980s, following the Reagan presidency.

While in Chico, Gitlin visited my house, which was then considerably smaller, prior to a pair of remodels, and, in the hallway, came across a bookshelf overloaded with volumes about the 1960s. He looked surprised, even perplexed at the numbers of works I had that were devoted to that era; his reaction, in turn, surprised and perplexed me. When I reminded him of my earlier request for information about I.F. Stone, he acted relieved that he had followed through in thoughtfully responding to me as he had.

I admired Gitlin’s activist history and tracked his return to academia, which led, in my estimation, to his two finest works: The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage and The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left. Like the man from the Old Left he so admired, Izzy Stone, Gitlin could be at different points kindly or irascible. He was always fiercely independent and intelligent, sometimes wise as when he wryly commented in 1995, “While the Right has been taking the White House, the Left has been marching on the English department.” He remained devoted to the left, to a democratic left determined to avoid sectarianism, dogmatism, and infantile pursuits. He is already missed, as a number of his friends have movingly acknowledged. He is also missed by those of us who barely knew him, did so only through his writings, or had encountered him all too briefly.

[Robert C. Cottrell, professor of history and American studies at Cal State Chico, is the author of All-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today and Sex, Drugs, and Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Rise of America’s 1960s counterculture.]

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Robert Cottrell, and Robert Cotrell’s Rag Radio birthday interview of Thorne Dreyer.

Thanks for this very wise tribute to Todd Gitlin. I, too, was a reader of I.F. Stone’s newsletter and learned from it.

I started reading the newsletter as an undergrad at UT. Initially, I picked up copies at the Coop bookstore, before subscribing. I spent countless hours at that bookstore, which was wonderful, as were Garner & Smith down on the Drag and the small bookshop on 24th just off it.

I greatly admire Allen Young’s own courageous activism.

I’m yet another I.F. Stone fan, I subscribed to his newsletter and own copies of all his published books.

I agree the two books by Todd Gitlin that Robert C. Cottrell identified are among his finest works, if not the finest. Gitlin’s book The Sixties is the best overall work on the social movements and upheavals of that decade.

As I completed two full days of interviews with Izzy, conducted in 1981 at his home in Georgetown, I readied to depart. But first, he led me to a case that contained copies of all his books. He then began pulling several off the shelves and offered me first one, then, another, and eventually more. Izzy inscribed each, including a rare edition of a collection of New York Post editorials from the 1930s. During the early part of that decade, he and Sam Grafton served as the leading editorialists for J. David Stern’s liberal newspaper. For the Post and earlier, the Philadelphia Record, another Grafton paper, each wrote from a left-liberal vantage point.

My task when I arrived home? To ascertain which of the unsigned editorials were Izzy’s, carefully poring over his precise language. At one point, I also rifled through bound volumes of The Nation and The New Republic, housed at the New York Public Library. The Nation’s front-of-the-issue editorials were unsigned. But the NY Public had original volumes with the name of the editorialist inked in, which greatly enriched my research into and eventual book on Izzy Stone.

Like Professor Jurie, I too consider Gitlin’s tome, The Sixties, one of the finest explorations of that era.

Thanks for this remembrance! I, too, knew Todd Gitlin almost entirely through his work, but in my case his very early work, not always identified as his, as an early national leader of SDS.

I met Todd only once, at Richard and Mickey (Hartman) Flacks’ home near Santa Barbara, CA; also the only time I met those two influential luminaries. I have no remaining idea how I came to be there, or in whose company, reflecting my well-honed skill in forgetting. I remember the day, one of those California specials that blends sunshine and ocean breeze with a bit of forest perfume. Todd and I walked on the beach below the Flacks’ beautiful house for maybe 45 minutes, just digging the day. I believe marijuana may have been involved. We discussed nothing of any import but it was a very comfortable interlude. I do recall this all took place some months after the bombing of a Bank of America branch in Santa Barbara. We talked about that some at lunch and Dick, as I recall (and you see what that’s worth!) said it was a real setback for local organizers, a pointless distraction from actual political work and hardly a blow against Empire.

Gitlin and the Flacks were part of a critical aspect of SDS formation and growth, perhaps the most necessary to our status as students: they were teachers. They were the kind of people who were sought out for their classes and who in turn sought out activist opportunities and supported student groups. We need more like them at every level of our broken educational system, or at the forefront of new ones.

Like Thorne and Alice, Mariann Vizard is one of the iconic figures who helped to make the Movement in Austin so vibrant and able to avoid, at least largely, the doctrinaire turn that afflicted it in various places.