Artist Robert Rauschenberg, Port Arthur native

A unique and creative artist, he was not afraid to cross boundaries, change media

By Lisa Gray / May 13, 2008

Texas native Robert Rauschenberg, the prolific painter/sculptor/jack-of-all-trades who for decades stretched the definition of art, has died.

“He was one of the greatest inventors, in art, of the last 50 years,” said Josef Helfenstein, director of the Menil Collection. “Since the 1950s, he reinvented art all the time. He changed media. He crossed boundaries. He has a unique place in the history of postwar art.

“Jasper Johns said that no one has invented more than Rauschenberg since Picasso — and I think that’s a good way to look at it,” said Helfenstein, who curated the 2007 Menil show Robert Rauschenberg: Cardboards and Related Pieces, the artist’s last museum exhibit.

Rauschenberg died of heart failure Monday night at his home in Florida following a short illness, said Jennifer Joy, spokeswoman for his New York gallery, PaceWildenstein. He was 82.

Born in Port Arthur and raised in the Church of Christ, as a boy, Rauschenberg planned to become a preacher. But at age 15, he changed his mind.

“I wasn’t proper for that job,” he once told the Chronicle, “because I was not going to see evil in everything, and I was not about to give up my own life to get the promise of one later. I’ll take my chances and make the best of this world.”

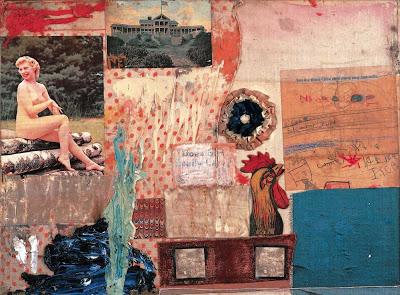

That love of life, with all its wildness and imperfections, was almost the only thing that defined his art. In the ’50s, when Abstract Expressionists held their paintings above messy everyday life, Rauschenberg dragged street junk to his studio and incorporated it into “combines” — scandalous-seeming combinations of painting and sculpture.

Bed consisted of his pillow and quilt, mounted on wood, then painted and drawn on. Other pieces incorporated tires, stuffed farm animals, police barriers, light bulbs, tennis balls and stained-glass windows. To Rauschenberg, everything was material.

Even other art. Once, he erased a Willem de Kooning drawing and declared his erasure to be art.

Another time, he recruited his friend the composer John Cage, to drive a Model A Ford over 20 sheets of paper. Automobile Tire Print, he called the resulting work.

Sometimes, his work wasn’t even an object, but an event. He frequently immersed himself in collaborations with dancers such as Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown. For 1963’s Pelican, he donned a helmet and parachute, then roller-skated to a sound collage of his own making.

In 1954, Rauschenberg met the then-unknown artist Jasper Johns. The New York Times said the intimacy of their relationship during the next years, a consuming subject for later biographers and historians, coincided with the production by the two of them of some of the most groundbreaking works of postwar art.

His vision of art was, literally, big. In Houston, a 1998 Rauschenberg retrospective curated by the Menil Collection spilled out of that museum and into the Contemporary Arts Museum and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. In New York, the same show commanded both Guggenheims.

During that retrospective, the MFAH showed 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece, a collection of paintings and sculpture that Rauschenberg had begun seven years before. It stretched 1,420 feet.

But even then, Rauschenberg wasn’t finished with it. He planned to continue it, he said, until “the final day.” It was a diary of his artwork, and he had no intention of retiring. He liked the idea that 1/4 Mile might someday grow to two miles.

In a review of Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective, former Chronicle art critic Patricia C. Johnson wrote that the 1998 exhibit “compresses five decades of ceaseless artistic investigation into 300 choice objects. It also reveals that, at 71, this seminal artist still is the enfant terrible he was when he began to rattle art’s cages half a century ago. The massive exhibit, spread across Houston’s three art museums, attempts to give shape to an artist who, like an ever-changing chimera, is quite impossible to pin down or summarize.”

Rauschenberg’s last museum show, at the Menil, coincided with a show of Rauschenberg’s recent photo collages at Texas Gallery.

“He loved to work,” said Fredricka Hunter of Texas Gallery. “He never wavered from that,” even after two strokes left him unable to use his right hand. He attended the 2007 gallery opening in his wheelchair, still a charismatic, powerful personality.

“He was probably the most important 20th-century hero that I’ll ever know,” Hunter said.

Born in Port Arthur on Oct. 22, 1925, Ernest Milton Rauschenberg adopted the name Robert and took his first art class at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1947 after serving in the Navy.

The GI Bill enabled him to study at the Académie Julian in Paris and the avant-garde Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where the legendary Josef Albers was teaching.

He settled in New York in 1950. It was the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, but Rauschenberg would have no truck with it.

He lived on day-old bread and buttermilk and imposed on himself “a kind of morality,” he told the Chronicle in 1998.

“If I couldn’t find material to do an artwork walking around the block once, I wouldn’t do it.”

In later years the block included the entire world: his home on Captiva Island in Florida as well as countries from Mexico to Tibet that have participated in his artists’ collaborative, the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange.

But his moral rule never fundamentally changed.

“I have a great curiosity, and I switch materials often when I can’t think of anything new to do,” Rauschenberg told the Chronicle before the three-museum retrospective in Houston.

“Problems turn me on. They are limitations, and somehow, limitations not only insist on what you can’t do but sometimes force you to do something that you couldn’t think of before.”

Rauschenberg is survived by his partner of 25 years, artist Darryl Pottorf, and his son, Christopher.

Copyright 2008 Houston Chronicle

Source. / Houston Chronicle

Also see Rauschenberg and Dance, Partners for Life / New York Times

The Rag Blog