For the fallen from Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, it’s home in a box, family and neighbors gather, a sad requiem, the flag folded, presented to the mother.

Nearly a half century ago this season of remembering the fallen — just after sunset on a hillside along the border of New York and Canada — the sad sounds of taps echoed through the hills and valleys. It was a warm evening summer of ’67 when hundreds of townspeople — nearly everyone living in Ausable Forks, a tiny hamlet of 500 or so souls — came out to pay last respects to a local boy, James Saltmarsh, killed a week earlier in Vietnam.

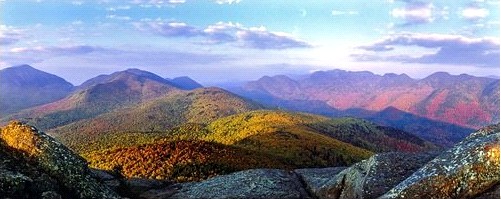

An honor guard had fired 21 rifle volleys as yet another son of the North Country of upper New York State was laid to rest. Finally, the elegiac lament of the bugle was heard, closing the burial ceremony in the breathtaking High Peaks region of the Adirondack Mountains.

It was just an ordinary rural burial ground, not a hallowed place dedicated to those fallen in America’s wars. Over the years I had become familiar with military cemeteries, having visited several abroad. I rarely came away unaffected by the magisterial simplicity of those solemn places that call to mind legions of eternal youth no longer walking the earth.

My first such experience was while passing through eastern Poland in the ‘60s. I was visiting a Polish colleague at a university near Lublin. He took me for a drive; he wanted to show me something.

We came to a small stately, fenced-in area. Entering, I realized it was a cemetery, but a very unusual one. There was just a single stone obelisk with Cyrillic script, standing guard so to speak, over rows of widely spaced, carefully landscaped low mounds, each with a bronze marker. This was the burial place of hundreds of Soviet soldiers who fell liberating Poland in 1944.

Without a trace of individualization, a fast moving army had buried its dead quickly and collectively.

Without a trace of individualization, a fast moving army had buried its dead quickly and collectively. The men of 8th Guards Army lay with their comrades, regiment by regiment. I was well aware of the staggering Soviet war losses, but still seeing them up close left me stunned.

An even more affecting sight greeted me years later in 1990 on the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Traveling by boat up the Volga, my companions and I went ashore at the place formerly called Stalingrad, the scene of one of history’s legendary battles, where well over a million Soviet and German soldiers met their deaths.

Our Russian guide, a young woman, led us to the Soviet victory memorial, a massive stone building on a bluff above the high banks of river. We entered the structure and were struck by its eight-story circular atrium accessed by an ascending walkway, every inch of the soaring walls carved with names of the dead. Quietly, pointing up the wall, the guide told me her grandfather’s name was inscribed there. What could one say — I bowed my head. To this day recalling the moment still brings a tear.

What of the North Country dead for whom there was no victory. They simply came home to local graveyards in the little towns and villages of the upper reaches of New York State where they grew up, played football, or marched in the band — places of several thousand residents with names like Cape Vincent, Hannibal, Phoenix, Rouses Point, Ticonderoga.

In the small town of Mexico on the shores of Lake Ontario in New York’s Oswego County — resonant with early American history of this part of the country — the local high school had lost three recent graduates in less than a year by fall of ‘67.

The great majority of the North Country dead were not drafted — they had enlisted.

The great majority of the North Country dead were not drafted — they had enlisted. Impelling so many to volunteer for an increasingly unpopular war was a region long in economic decline. Prosperous in the late 18th/early 19th centuries, by the mid-20th the local industries had seen better times.

Logging was greatly restricted, sawmills shuttered, mining played out. Most of the riverside mills were long shut down, their giant water wheels turning aimlessly, as most of the pulp paper companies had moved South in pursuit of cheap labor and less environmental concern.

By the ‘60s, the North Country had become a region of little economic opportunity for the boys coming out of the small town high schools. Sure, there were community colleges scattered throughout the region at which draft deferments awaited, but many of the local guys grew up on farms and had neither interest nor money for pursuing further education.

With Adirondack unemployment 50 percent above the state average, the military beckoned to the young men of the North Country, attracted by the combination of adventure, challenge, and, not least, a paycheck. As one 20-year old enlisting at a local recruiting station put it, “There just isn’t much for a young guy to do.”*

Many of the volunteers had been athletes, opting for the Marines or airborne. Often they virtually went from the football field to distant battlegrounds with exotic names like Dak To, Quang Nam, Khe Sanh — for so many, places of no return.

The journey was all too frequently a short one. Vietnam tours were 12 and 13 months, and when a soldier was done, he could head home, “back to the world” as they called it. Some 58,000 never completed their tours. They’d go off to war — Basic Training, Advanced Infantry Training, deployment to Nam, often cut down by enemy fire or a land mine early tour, mid-tour, and sometimes just weeks before return. Next of kin notified.

During WWII, notification was by the dreaded telegram, the Western Union guy.

During WWII, notification was by the dreaded telegram, the Western Union guy. In modern wars with their “lighter” casualties, the bad news can arrive at warp speed, and is delivered by military personnel. Recently in Mechanicville, New York, just south of the Adirondacks — by area the smallest town in the state — a middle-aged mother awaited a call from her Marine son.

Since deployment to Afghanistan just weeks earlier, he rang home every Sunday morning at 6 a.m. His mother set the alarm, rose early, but no call. A few hours later a knock at the door — two Marine officers broke the heartbreaking news, her son had been killed 24 hours earlier — shot in the neck, just over a month in-country. She told the press he had wanted to serve in Afghanistan adding, “I’m extremely proud of my son.”**

For the fallen from Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, it’s home in a box, family and neighbors gather, a sad requiem, the flag folded, presented to the mother — almost always the mother — the gravediggers at a respectful distance waiting to turn to the final task. What then of the enduring casualties of war, of all wars, those left behind, parents, young wives, fatherless children.

From the mother and father of a Russian soldier killed in the Soviet Afghan War, a final message carved on his tombstone, “Dearest Igor, You left this life without having known it.”*** The lost one is of course buried in the hearts of those who loved him, left now with just memories and photos.

Some years after Vietnam, in a documentary on the war, an older couple was filmed sitting quietly in their living room, a picture of a young man in uniform in a silver frame between them, their only child, a pilot shot down over North Vietnam. Coping with loss, not for them the revisionism of defeat — we shouldn’t have been there, lives wasted — no, the war remained a just cause, their son died doing his duty, they were ever proud.

Or fighting back tears, the same sentiments expressed more recently by the mother of an Afghan GI, Sgt Orion Sparks: “He didn’t shirk any of his years…. I felt honored that he was my son and I was able to be part of his life.”****

Long after the guns go silent…the boy who went to war remains, forever young, in the silver frame on the mantle.

Long after the guns go silent, time passes, rights and wrongs fade — the parents grow old, the young widow remarries, children grow up, move away, but the boy who went to war remains, forever young, in the silver frame on the mantle. The strange poetry of war obits, the military fanfare at graveside, the heartrending notes of taps closing a life — all become distant memory. Pain dulls, never goes away.

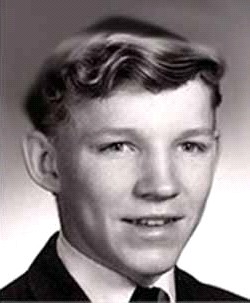

The young men in those picture frames remain unchanged, the boy who went off to war looks as we last remember him. And so it was with my brother Jeff Sharlet who served in Vietnam, was possibly exposed to something there — possibly Agent Purple, we don’t know — and died several years later at 27. For our parents, now long gone, as for all those North Country families, Igor’s parents in Russia, and the mothers of those two Afghan GIs — in spite of reaffirming sentiments — nothing could have been worse than losing a child.

I remember the day we buried Jeff. It was a beautiful sunny June day in ‘69. I sat between my parents as the limo sped along broad avenues toward the cemetery, the hearse flanked by two outriders — booted, helmeted motorcycle policemen in reflecting sunglasses astride big Harleys.

To my distraught mind, two images came to the fore — a scene from the 1950 French film Orpheus when death, a striking woman cloaked in black, arrives by limo, preceded by goggled motorcycle outriders, submachine guns slung, announcing her authority; and then as we approached the gates of the cemetery, the more gentle image from the lines of Emily Dickinson’s poem:

Because I could not stop for Death,

He kindly stopped for me …Since then ‘tis centuries; but each

Feels shorter than the day

I first surmised the horses’ heads

Were toward eternity.

*New York Times, July 12, 1967

**Albany (NY) Times-Union, December 3, 2012

***S Alexievich, Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War (1992)

****Military Resistance #10J11, October 21, 2012

[Robert Sharlet, a long time academic, is co-authoring a memoir of his brother Jeff — a Vietnam GI and, subsequently, a leader of GI protest against the war — with his son and namesake, Jeff Sharlet, the writer. In the interim, the author writes a biweekly blog, Searching for Jeff.]

On one level, the loss is the same, regardless of the war in which it occurred. But there is a quite fundamental difference between the soldiers of the Red Army who died heroically fighting against Nazism at Stalingrad and the soldiers of the US Army who died fighting for US imperialism in Vietnam and Iraq. There is no honor in the latter. Context matters.

As a 21 year old in the US Army in France, I visited Verdun, where a million died in the bloodiest battle of WWI, a battle that essentially ended in stalemate. Graves stretched to the horizon in every direction. It was a sight I’d never forget.

Sharlet’s article was a moving reminder of the cost of war to the family, friends and community of those who were/are wounded physically, cognitively, emotionally or die while serving their country. Soldiers, indeed the public at large, rarely understand much less control of the overriding political or economic “context” in which they serve. But such context does not comprise a “fundamental difference” in honor or respect due them.

What a waste war is..be it in foreign fields, where action is

doubtful, or “fields” nore clear..streets in speeding cars,

irrigated by alcohol, streets with craziness of gangs and

often even mistaken targets, or schools-churches-apts.where mental health, that should have been watched over long ago, enacts another drama of young, promising

kids are laid to rest..Why so much violence? Like a box full of rats in a reachers diggings, who are so crowded that

the eat each other.

Robert Sharlet is correct that, “Coping with loss, not for them the revisionism of defeat — we shouldn’t have been there, lives wasted — no, the war remained a just cause, their son died doing his duty, they were ever proud.” The death of a parent, a child, a sibling, a friend, or any loved one in a war, “just” or “unjust,” will be rationalized or justified in the minds of those left behind. For many it is just too hard, too painful, to not rationalize the death of a loved one regardless of which war the death occurred.

While it is true that Vietnam and Iraq were unjust wars of US imperialism, the truth is, Vietnam and Iraq were very different. Vietnam evolved from 1800s French colonialism in French Indochina, into the post WWII the desire to get France and Europe back on their economic feet, to get the Michelin Group back to harvesting rubber, and from the Cold War politics that sucked the USA into Vietnam. (Rubber was a huge issue in WWII and there were no really successful synthetic rubbers until the mid-1960s.) As the Vietnam War evolved from a 100 years of bad polemics, it is difficult to lay the entire blame on any one administration.

But the invasion of Iraq was a bad decision by a few old men in Washington, DC.

“With Adirondack unemployment 50 percent above the state average, the military beckoned to the young men of the North Country, attracted by the combination of adventure, challenge, and, not least, a paycheck. As one 20-year old enlisting at a local recruiting station put it, “There just isn’t much for a young guy to do.”*” It is a crime that so many of us who volunteered because we could not get a job due to the threat of the draft hanging over our heads, or because of the promise of the GI Bill and the opportunity to get a college education when returning to “the world.” Yet, so many of those returning have physical and emotional scars that prevent them from successfully integrating into society.

Thanks to Robert Sharlet for reminding us of the futility of war, and I am sorry for Sharlet’s loss of his brother… and good friends I served with in Vietnam who did not return, yet I did. The only time in my life that I saw my Dad cry was the day I got off that plane in Lubbock.

Peace, Terry J. DuBose, Vietnam 1967-68.

This movie says so much.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AMwy9SLhaD4

FDR promised Ho Chi Minh that the US would support Vietnamese independence if they fought the Japanese. They did, but Truman broke that promise and backed the reimposition of French colonialism. Every US administration, Democrat and Republican, from Truman to Nixon had a hand in making US aggression in Vietnam worse. W and Obama combined for the debacle in Iraq. Imperialism is bipartisan.

I was very moved by Sharlet’s words. It brought to mind a gathering on Memorial Day weekend several years ago at Under the Hood Cafe near Fort Hood. There was no pomp, no pageantry. It was a memorial for a young woman veteran who died from inadequate healthcare and a deadly combination of alcohol and pain medication.

With suicides among veterans now higher than combat deaths, we must also remember those soldiers who have taken their own lives. And, along with Iraq Veterans Against the War, we must defend veterans’ Right to Heal.

When storm troopers die in the course of bringing yet another nation to heel for their empire, it might be tragic, or even courageous, but it’s not heroic. Unless a soldier dies or is wounded defending their nation, or even defending the greater good from insane and horrible evil, as we did in the first half of the last century, then they are not heroes. They are simply uniformed enforcers paid to pursue the goals of an imperial puppet administration.

When storm troopers die in the course of their work, its a personal loss to their families and friends, but they are not made heroes because of the loss. Calling them such is part of the state led propaganda effort to legitimize extending the tentacles of an empire.

When I have conversations with others and they refer to a soldier as a hero, I remind them of the difference between an actual hero and a storm trooper.

I have to give the Rag Blog credit specifically and the writers and thinkers in the anti-war movement as well, for opening my eyes to this issue. I used to wrap myself in the flag and believe each orchestrated and pre planned world event was just more proof of how much the world hated us for our liberty and values. Eyes are open now.

– Extremist2TheDHS