Widening roads in cities like Austin only makes congestion worse as political pressure works against smart transportation planning.

IH-35 near downtown Austin: the most congested road corridor in Texas. Image from CultureMap Austin.

Don’t get involved in partial problems, but always take flight to where there is a free view over the whole single great problem, even if this view is still not a clear one. — Ludwig Wittgenstein

AUSTIN — Contrary to much public opinion, congestion in fast-growing cities like Austin cannot be relieved by expanding roadway capacity because existing congestion and latent demand soon shift and fill up the newly added capacity.

To make sense of why there is still such strong political support for expanding capacity on IH-35, we need to understand Texas road politics, as reflected in the Texas Department of Transportation’s history and current policies. Past and current attempts by TxDOT to build enough roads to deal with increasing demand have left TxDOT with more than $20 billion in debt, plus a backlog of unsustainable construction and road maintenance obligations, despite a policy in support of privatized toll roads.

Over time, suburban sprawl trends overwhelm the major highways in all large U.S metro areas during the daily peak, reducing mobility and causing gentrification, which then worsens the congestion.

There is now political pressure on the city to support trying to “fix” IH-35 with a speeded-up November 2016 transportation bond election. Because of TxDOT’s financial problems, it seeks to add new IH-35 capacity at the lowest cost. This approach conflicts with the existing community goal to depress and cover IH-35 through downtown Austin.

The experience of widening the Katy Freeway in Houston has left it more congested than ever.

The experience of widening the Katy Freeway in Houston, now the world’s widest road, has left it more congested than ever. As one indication that car-centered approaches aren’t working, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner recently told TxDOT that he seeks to shift to a new transportation planning approach that focuses on non-road alternatives like rail.

Austin’s congestion is now about as bad as Houston’s. Austin, like Houston, has the option of making a conscious shift toward a planning approach which integrates land use planning with transportation planning, in ways that minimize both construction costs and traffic congestion. So far, the growing political pressure in Austin to strongly fund transportation alternatives to roads is not very well focused, nor is it welcomed by TxDOT.

Assuming that an Austin transportation bond issue is placed on the November ballot, this would offer an excellent opportunity to begin a smarter approach that is not based on road projects. In particular, light rail along the north-south Lamar travel corridor would be an excellent opportunity because of both congestion and the scale and type of existing corridor development, which is a good match for light rail’s mobility characteristics.

- Widening congested roads like Austin’s IH-35 increases the congestion

- Texas road politics

- Traffic congestion leads to gentrification, which intensifies sprawl trends, making congestion all the worse

- Central Texas’ CAMPO Plan reflects Texas growth politics

- TxDOT: An agency in chronic financial distress

- November 2016 Austin transportation bond election: A rush job

- Shall the downtown section of IH-35 be depressed and covered?

- Austin could choose its own future, as Houston is trying to do

- What Austin does about IH-35 will determine what kind of city Austin becomes

- The case for rail as soon as possible; we have already done the planning

♦ Widening congested roads like Austin’s IH-35 increases the congestion

This analysis will begin by documenting the strong case against widening roads like IH-35 as a way to relieve congestion. This concept is important to understand because TxDOT is now planning to increase the lane miles and vehicle capacity of IH-35 from San Marcos to Georgetown at an estimated cost of $4.3-$4.6 billion. This road section is now ranked as the most congested corridor in Texas.

The general consensus among experts is that trying to relieve congestion by widening roads in a very congested city like Austin will actually increase traffic congestion. Severe traffic congestion throughout a city during peak hours means that drivers will seek out and fill up any new road capacity, as part of the process of congestion avoidance equalization, as fast as new capacity can be added. Adding new corridor capacity attracts traffic from the other areas of a city suffering from widespread peak hour congestion only leads to a new and fairly uniform level of driving misery. The example of I-10, the Katy Freeway in Houston, serves as a good demonstration of this fact as noted by the U.S. PIRG report: Stop Highway Boondoggles.

In Texas, for example, a $2.8 billion project widened Houston’s Katy Freeway to 26 lanes, making it the widest freeway in the world. But commutes got longer after its 2012 opening: By 2014 morning commuters were spending 30 percent more time in their cars, and afternoon commuters 55 percent more time.

The familiar American car-based suburban sprawl pattern of urban development around cities tends to occur by default whenever the urban population is increasing and when there is also enough easy funding to keep building roads. The effect of adding more layers of suburban sprawl development outside growing cities is well recognized as a cause of severe urban traffic congestion across the USA.

Austin traffic congestion from building roads to serve sprawling unregulated development.

Austin’s daily bumper-to-bumper peak congestion on both IH-35 and MoPac have gradually gotten to the point that it has because of decades of adding more car-addictive sprawl development. Nothing can now reverse this congestion syndrome very fast, very cheaply, or very easily. Austin’s traffic congestion is the normal outcome to be expected when we keep building roads to serve sprawling unregulated development around a growing city for more than half a century.

In past decades, the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) had effectively functioned as a pro-highway think tank friendly to TxDOT and the highway beneficiaries. Understandably, and until recently, TTI has been reluctant to admit that building more highways does not relieve congestion. An analysis of TTI’s own yearly reports on urban traffic, currently at this link, found that building roads was not an effective way to relieve congestion. The analysis was done by the reform-minded Surface Transportation Policy Project documented this finding in 1998 in a report titled “An Analysis of the Relationship Between Highway Expansion and Congestion in Metropolitan Areas.”

By analyzing TTI’s data for 70 metro areas over 15 years, STPP determined that metro areas that invested heavily in road capacity expansion fared no better in easing congestion than metro areas that did not. Trends in congestion show that areas that exhibited greater growth in lane capacity spent roughly $22 billion more on road construction than those that didn’t, yet ended up with slightly higher congestion costs per person, wasted fuel, and travel delay. The STPP study shows that on average the cost to relieve the congestion reported by TTI just by building roads could be thousands of dollars per family per year. The metro area with the highest estimated road building cost was Nashville, Tennessee with a price tag of $3,243 per family per year, followed by Austin, Orlando, and Indianapolis.

What happens when you do try to pave

your way out of congestion.

This 2012 analysis by David Dilworth, “You Can’t Pave Your Way Out of Congestion!,” explains what happens when you do try to pave your way out of congestion.

- There is now overwhelming evidence, including a nationwide study of 70 metropolitan areas over 15 years (Texas Transportation Institute), and another California specific study (Hansen 1995, which included Monterey County) that when an area is congested — additional lanes or roads do not provide congestion relief.

- It is also well documented that additional lanes increase traffic, and that new highways create demand for travel and expansion by their very existence.

- Further experience shows “When road capacity shrinks — So Can Traffic”; traffic congestion goes down!

So, when a road is congested, adding more lanes or roads will not relieve congestion, but will likely increase traffic.

When a road is congested the only way to relieve congestion is not by building more roads, but by reducing land use — or paradoxically by closing roads.

The futility of building more roads to reduce congestion suggests that our own urban transportation planners should give special consideration to the lower cost, and energy savings of alternative mobility approaches focused on transit, bikes, and walking. Nowadays, even TTI is finally admitting that IH-35 can’t be fixed in any meaningful sense. True, you can add some lane capacity. You can also make this road somewhat less conspicuously imposing in its impact on the inner city by depressing IH-35 through downtown and capping it over. However nothing will lead to significantly less congestion as these snips taken from an August 2013 TTI report indicate.

This modeling research demonstrates that Central Texas cannot “build its way out of congestion” on IH-35. Examination of the initial set of scenarios demonstrates that, as capacity is added to IH-35, traffic moves to IH-35 from other streets and roads that operate with even worse congestion, in essence “re-filling” the road. As described above, Central Texas drivers fill any capacity added to IH-35. Therefore, additional capacity provides little relief to peak-hour IH-35 general purpose lane congestion. And, because population and jobs are projected to grow so much in the corridor, any open road space created by new lanes is quickly filled. (Executive Summary – 6)

‘Key Finding: Long-Term Solution Must Include More than Added Capacity’

This modeling research demonstrates that Central Texas cannot “build its way out of congestion” on IH-35. Examination of the initial set of scenarios demonstrates that, as capacity is added to IH-35, traffic moves to IH-35 from other streets and roads that operate with even worse congestion, in essence “re-filling” the road. As described above, Central Texas drivers fill any capacity added to IH-35. Therefore, additional capacity provides little relief to peak-hour IH-35 general purpose lane congestion. And, because population and jobs are projected to grow so much in the corridor, any open road space created by new lanes is quickly filled. (P60-61).The study team concluded that this effort demonstrates a very unlikely future. That is, the levels of congestion predicted for IH-35 — in fact, the Central Texas region — will be unacceptable for local residents and business. In discussions with the MIP Working Group regarding these technical results, there is heightened concern that the levels of congestion demonstrated by this study would dampen the area’s growth in population and employment because people and businesses will quite simply not move here if the transportation infrastructure is insufficient to avoid this level of congestion. Therefore, with impacts predicted to be this substantial to quality of life and economic health, such levels of congestion will likely be unacceptable to future residents and businesses, so that the area’s growth is in fact, unsustainable. (P61)

TxDOT has no idea of where it will get most of the money to widen IH-35.

TxDOT’s Texas Transportation Commission is currently allocating funds to construct isolated parts of its full IH-35 widening vision along IH-35 inside Austin. The TTC recently granted $158 million for Austin IH-35 projects this year. At the same time, TxDOT has no idea of where it will get most of the money to widen IH-35, so it is calling on the public to suggest “innovative funding solutions.”

To date, funding has not been identified for most of the Mobility35 projects. The funding status for each Mobility35 project can be found on the individual project’s webpage. Funding the Mobility35 program will require collaborative action from local, state and federal agencies, as well as from citizens and elected officials. If you have ideas for innovative funding solutions, please contact us. You can also visit the Federal Highway Administration for more information on transportation funding.

Neither the probable lack of any reduction of congestion nor the lack of funds for most of the IH-35 construction work seem to be a major problem so far as TxDOT is concerned. TxDOT has set up the “Mobility35 “planning effort to promote its road-widening (or at least capacity-increasing) project. This joint effort policy and road design study, which involves TxDOT, Austin, and other cities like San Marcos and Georgetown, has been going on about five years, with a lot of public meetings. Austin donated about $3 million to do this IH-35 planning, and also about $9 million to fund 51st Street IH-35 overpass reconstruction.

♦ Texas road politics

What result do the public officials want to achieve on IH-35? If we try to understand the Austin transportation policy that led to IH-35 as an isolated case, it doesn’t make much sense. Why spend billions to increase capacity on IH-35 while knowing that this will make congestion worse, and while knowing that the money to do it isn’t there without the addition of a lot of local funding? Why should we be considering funding road projects like IH-35 by using a speeded-up November 2016 bond election? Most of the added capacity, the major benefit as seen by TxDOT, would not be seen for five or more years. The express lanes for buses would probably take 10 years, with a lot of chronic construction annoyance on IH-35 until then.

Roads have gotten to be a lot more political

over the last decade.

We need to try to understand the IH-35 plans in the larger context of TxDOT and Texas road politics. Roads have gotten to be a lot more political over the last decade as a natural consequence of the fact that the money to build and maintain roads has been running short at every level of government. The federal FHWA which funds roads, and the FTA which funds transit, are both chronically underfunded. U.S. transportation infrastructure has become notoriously dilapidated. At the same time, transportation funding reform has been paralyzed by partisan infighting in Congress.

At the federal level, this situation has led to a series of federal transportation funding extensions; political band-aids rather than serious budgetary reform. The refusal of both Texas and the federal government to raise their fuel tax for more than 20 years is sufficient evidence that transportation funding has gotten seriously out of balance with funding reality. The denial of the need to raise fuel taxes to match rising road costs is hurting TxDOT’s ability to maintain its 195,000 lane miles of existing roads, especially in the shale drilling areas. For TxDOT to try to keep funding urban roadway expansion projects which don’t relieve congestion but which will demand an increasing maintenance cost is clearly an unsustainable trend.

At the same time, less federal funds translates into less legal oversight from the federal level. As one example, the federal road agency, the FHWA, is now letting TxDOT conduct environmental studies from inside TxDOT rather than under the former federal jurisdiction; akin to licensing foxes to guard the hen house to save money.

All governments, as we know them and by their nature, try to encourage economic growth. In Texas, as with most Sun Belt metropolitan regions that grew since the 1940s, cars, trucks, and roads have all become essential components of urban growth. “Sunbelt Cities; Politics and Growth Since WWII,” a classic 1983 study by Bernard and Rice, explored the patterns of growth and growth politics across the rapidly growing U.S. South. By this time the highway-sprawl growth pattern of metropolitan growth had already become well established.

The chapter on San Antonio by David R. Johnson describes the political situation after a business coalition, the Good Government League (GGL), gained political influence in San Antonio together with its road bonding ability.

…the GGL was more interested in building roads as stimulants for urban growth than in repairing old streets in already settled neighborhoods. The bulk of the bond money was earmarked for the purchase of rights-of-way for expressways. Since 1946, the Chamber of Commerce had advocated a vigorous highway building program. Until the emergence of the GGL, however, the chamber had been unable to attract sufficient political support for its views. Thus when the Federal Highway Road Act of 1956 made possible a massive national road building program, the business leaders had the crucial support they needed. The chamber prepared and presented to the Texas Highway Commission a comprehensive plan for expressway construction in the San Antonio metropolitan area.

In 1974 when the first energy crisis hit the USA, Griffin Smith Jr. wrote an excellent, well-researched account of how the Texas road lobby came to be, its wide network of political allies devoted in common to building roads, and the effort to make roads, driving, and big homes a permanent aspect of Texas lifestyle and culture. See “The Highway Establishment and How it Grew and Grew and Grew.” So it was in Texas then, during the first energy crisis, and so it has been in Texas for more than 40 years since without great political change. Molly Ivins used to call TxDOT the “Pentagon of Texas.”

The Governor appoints his friends and campaign contributors to state agencies as political favors.

There is now an established pattern of money, roads, and politics whereby the Texas Governor appoints his major friends and campaign contributors to state agencies as political favors. In this respect, appointment to TxDOT ranks near the top as a valuable political appointment. If a Texas governor stays in office for a long time, as Rick Perry did, he can appoint all the Texas Transportation Commission (TTC). Because of overlapping terms, these appointments even stay influential for a time after a governor leaves. This TTC then has the political authority to decide when and where to build the state roads that almost all local governments seek.

In fact there is now a sort of bidding war in which various local and regional governmental coalitions compete in trying to provide TxDOT with matching funds to get roads built faster. It should come as no surprise that the roads in favor often tend to benefit the land developers and road contractors and special interests who reward the Governor with campaign contributions.

According to a detailed analysis by Texans for Public Justice, the special interests tied to the the $175 billion Trans-Texas Corridor project, like road contractors, gave Perry and other Texas politicians $3.4 million dollars in campaign contributions from 2003-2008, the period when Perry was leading the political support for this massive but highly unpopular project.

Given the historic lack of state land use regulation outside the city limits of Texas cities, there is still, in principle at least, a potential opportunity to shift to smarter land use rules and regulations. (Texas cities do have some “extraterritorial jurisdiction” powers which don’t reach very far.) More than 86% of the total Texas population is now urban and Texas has largely outgrown its rural heritage. The major Texas metropolitan areas, the big glowing regions you see from a jet plane at night, really function as sprawling but regionally integrated economies. Ideally these major Texas metro areas should be governed as communities, without the burden of conflicting and overlapping layers of city and county government.

One motivation for this situation, suburban sprawl development, is now an accepted way to redistribute wealth from cities to their suburbs. Texas’ suburban real estate developers thus stand to benefit from the exploitative pattern of income redistribution from the city to the suburbs made possible by TxDOT’s publicly-funded roads.

In Texas, roads are about 80% funded by a combination of TxDOT and federal fuel tax revenues, about 20 cents per gallon for each one, with different rules attached. TxDOT has great institutional power based on its authority to fund roads to serve regional land development. This authority is almost irreversible because it’s incorporated in the Texas Constitution. TxDOT’s authority remains primarily devoted to serving the exponential increase in cars and trucks foreseen by TxDOT’s travel demand projections. Under state law, TxDOT funds roads but little transit. Transit in Texas largely is left to fend for itself, obliged to rely on local funding like Austin’s Capital Metro penny sales tax or new bond debt, together with shrinking federal transit help.

I have written extensively on Texas transportation politics for The Rag Blog and links to my earlier articles can be found below.

♦ Traffic congestion leads to gentrification, which intensifies sprawl trends, making congestion all the worse

As they say, we can pay now or we can pay more later. If Austin were a human patient coming to a doctor with a case of advanced congestion, the doctor would start by leveling with the patient, explaining how decades of bad habits had finally caught up as clogging of all the main traffic arteries, and how any delay in a shift to a different lifestyle will only make the condition worse. A serious if politically unpopular commitment to reform is needed to keep the patient alive.

In the case of Austin, this mobility decline could translate into a broad avoidance of Austin as an increasingly expensive and impossibly congested location for tech growth. Austin traffic congestion has now gotten to the point that it is a serious concern to Austin area business interests, a looming impediment to growth that is stubbornly resistant to affordable relief.

Austin congestion is the natural result of rapid regional population growth, led in recent decades by an Austin tech job boom together with unregulated sprawl outside the city. Over time, high tech job growth must come into natural conflict with the sprawl growth interests which politically impose a top-down growth policy through CAMPO. With fast tech hub growth and unrestrained sprawl, Austin became congested faster and worse than most cities of similar size.

Over time, congestion and decreasing urban mobility lead to gentrification.

Over time, congestion and decreasing urban mobility lead to gentrification. Rising property values plus rising per capita growth debt are reflected in rising property taxes and living costs. This means the core city’s low income service workers are increasingly forced to relocate outside the city in lower cost suburbs. They drive in on a few main highways, which further increases gentrification and congestion.

This decrease in Austin affordability has been a particular burden for Austin’s African-American population who, for a variety of reasons, have moved out to suburbs such as Pflugerville. As a University of Texas study observed, “All told, the combined effects of concentrated segregation and concentrated gentrification of Austin’s historic African-American district provide a partial explanation for the rapid decline in African-American residents between 2000 and 2010.”

In fact, all sizable U.S. cities are suffering from rapidly decreasing mobility and increasing congestion. Austin does not even rank near the top by most measures of congestion, because the car-centered mobility decrease is actually part of a national syndrome described by Statesman reporter Ben Wear.

Austin’s scores in virtually every category of the report have degraded since 2012, as have traffic conditions nationwide. The report declares that “the national congestion recession is over. Urban areas of all sizes are experiencing the challenges seen in the early 2000s — population, jobs and therefore congestion are increasing.”

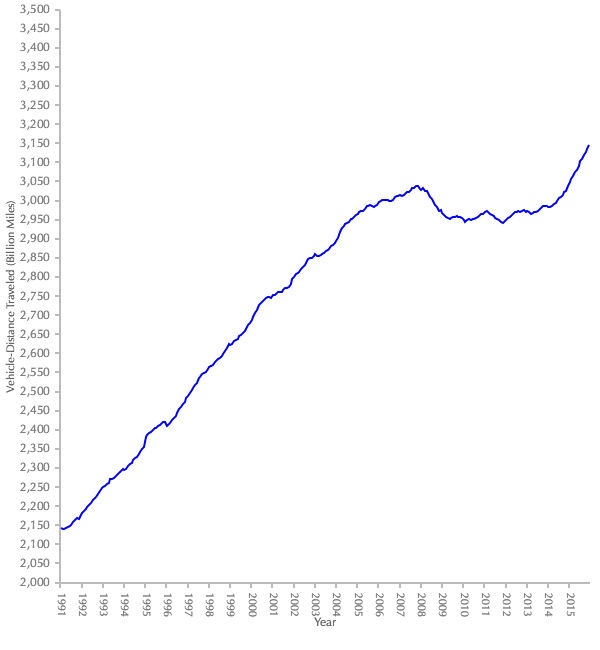

For the moment, we have cheaper gasoline. As we might imagine one consequence of cheap gas is that driving has been reviving nationally as this FHWA traffic volume trend driving chart shows.

December 2015 traffic volume trend. Figure 1 – Moving 12-month total on all highways. FHWA chart.

The FHWA chart is based on a lot of carefully collected data from many stations across the USA. The likely economic picture it portrays is that U.S. driving peaked around 2006, and then sank for a few years due to high fuel prices and a stagnant economy until around 2014. Driving then recovered in mid-2014 due to an abrupt collapse in oil prices. Cheaper driving plus gentrification means commuters driving further to save money to escape rising city costs. Folks priced out of Austin may move to Elgin, etc. Home prices have recently seen rapid increases in Houston and Dallas as well as Austin; this is a national pattern.

This strong revival in U.S. driving means that the next oil price spike will hit drivers all the harder.

Those who understand energy economics should know that this strong revival in U.S. driving really means that the next oil price spike will hit drivers all the harder when it comes in a few years. Art Berman is an energy economist and geologist whose expertise in fossil fuel economics is highly regarded among his peers. Here is a recent example of his analysis of the current trends. See especially slide 3: “Under-investment will cause a sharp oil-price rebound in a few years”.

♦ Central Texas’ CAMPO Plan reflects Texas growth politics

Operating under the authority of federal Metropolitan Planning Organization law, the CAMPO planners have the legal authority to make key transportation funding decisions for the big six-county Central Texas region that includes and surrounds Austin. The CAMPO 2040 plan anticipates ever more roads, cars, far-flung suburban sprawl growth, and increasing congestion for decades to come; in other words business as usualfor as long as possible.

TxDOT, which strongly endorses the CAMPO 2040 Plan, is represented as a voting member on CAMPO by TxDOT District director Terry McCoy. Hays and Williamson Counties have now effectively formed a suburban county political alliance with Bastrop, Burnet, and Caldwell counties. Together with TxDOT support, this alliance is able to politically dominate Austin and Travis County on the CAMPO Board. I described how the planning worked two years ago, here. Not a lot has changed since then, except the politics that attends scarcity has gotten more intense.

As things currently stand, the new long-range CAMPO 2040 Plan proposes to spend $35 billion dollars to intensify the current sprawl growth pattern of Central Texas development, while doubling the regional population from about 2 million to about 4 million. The Plan proposes to put 70% of this CAMPO regional growth not just outside Austin, but even outside Travis County. This planning also means acceptance of worsening congestion. It is is now Austin’s official planning future in both state and federal eyes, for transportation funding purposes. Under this mode of planning, the controversial roads with political clout like SH-45 SW, and MoPac South race ahead in their funding and construction priority, leaving transit far behind.

CAMPO’s long range funding and construction plans are federally required to be updated every five years. The previous plan, the 2035 CAMPO Plan had a lot of low density suburban sprawl development, but the new CAMPO plan has even more. There is no longer a transit-friendly transportation alternative in the 2040 CAMPO plan as there was in the 2035 Plan. Federal law does not require that that there be such an alternative; the choice now is either to build the planned roads to serve sprawl development or not to build them.

The CAMPO 2040 plan leaves no

developer behind.

So far as proposed future road capacity is concerned, the CAMPO 2040 plan leaves no developer behind, and word has gotten out. To give one local example, Canadian land speculation investment group Walton Development owns and plans to develop about 15 square miles of raw land in the Austin area.

Walton Development and Management is preparing to make a big splash in Central Texas even though the company has had boots on the ground here since 2007. The Canadian-based land investor and master-planned community developer has seven communities in the pipeline in Central Texas, following years of researching the market and building relationships with consultants and government officials. Collectively, Walton owns 83,000 acres in Canada and the U.S. — and has quietly amassed about 10,000 acres in Central Texas…

The Calgary, Alberta-based company has been assessing numerous U.S. markets in the wake of the subprime mortgage meltdown and the Great Recession. Central Texas, predominantly south and east of Austin, has risen to the top of its hot list, as well as Washington, D.C.; Atlanta; Charlotte, N.C.; Orlando, Fla.; Dallas; Phoenix; Tucson, Ariz.; and Southern California…

The approved 2040 CAMPO Plan openly admits that even if the CAMPO region finds its hypothetical projection of $35 billion in future funding (highly unlikely) to implement the approved plan perfectly, then Austin area congestion will keep on getting steadily worse until 2040.

Important resource limits like fossil fuel emissions, fuel costs, and regional water constraints (documented by the Texas Water Development Board) are all conspicuously missing from CAMPO’s population projections and future travel demand models. The CAMPO 2040 Plan anticipates a major shift from state and federal funding to local funding. This funding assumption has ominous implications from the standpoint of implied property tax increases for projects like IH-35.

♦ TxDOT: An agency in chronic financial distress

As seen through its policies and actions, TxDOT is deeply and institutionally devoted to building all the roads that it can, and as fast as it can, to handle ever more road traffic. The politics in support of cars, trucks, and more roads is now solidly institutionalized.

TxDOT is now so politically powerful and central to Texas economic growth that the major threat it now faces as a state agency is money. It’s both running out of current revenue, and also its formerly easy ability to keep borrowing more.

If IH-35 is the most congested corridor in Texas, then TxDOT’s natural response is to do whatever is needed to increase the road capacity. There is no alternative plan, except to do the same thing more slowly if the funds are lacking. The funds have been running short of TxDOT’s anticipated needs for a long time. This explains why TxDOT got into the toll road business decades ago, initially in-house through the closely allied Texas Turnpike Authority.

Despite a shift toward toll roads, TxDOT’s funding shortfalls have been growing.

Despite a shift toward toll roads, TxDOT’s funding shortfalls have been growing. TxDOT now better understands that toll roads are not necessarily money makers. An IH-35 reliever road deal set up with TxDOT blessing, SH 130, just declared bankruptcy. TxDOT now seems to regret having ever gotten into the risky and often unprofitable toll road business. When it became clear that toll roads were no magic funding solution, TxDOT switched to the promotion of privatized Regional Mobility Authorities or RMAs.

When Ric Williamson was chair of the TTC, which determines TxDOT policy, he strongly encouraged the formation of these TxDOT helper agencies, the RMAs, with their chairs appointed by the governor. Such bodies, like Austin’s CTRMA, can borrow from Wall Street to issue Muni bonds to build these “Public-Private Partnership” toll roads. That is why TxDOT invented the RMAs like the CTRMA, to try to shift the road funding burden onto the private sector with toll road muni bond debt.

However, these toll road bonds are still rated as being rather high risk by the bond rating houses since they depend on decades of steady suburban sprawl growth to avoid default. The CTRMA’s new subordinate debt is rated just above non-investment grade junk bonds, and is considered too risky to insure, unlike the CTRMA’s initial toll road bonds.

There is little doubt that TxDOT has a serious ongoing solvency challenge, which I have written about before. TxDOT is a state agency that now has to spend more than 10% of its total yearly income just to pay interest on its massive accumulation of road debt.

The Texas Department of Transportation just issued its audited financial statements for 2014. They’ve rung up a debt balance of $19 billion. It was only $4 billion back in 2006. That’s when Rick Perry went on his debt binge. Of the $7.3 billion tax revenues TxDOT will take from Texans in 2016-2017, more than $2.4 billion will go to making debt payments.

TxDOT is being kept going by means of periodic Texas legislative bailouts.

There are few signs that TxDOT finances are improving, although it is being kept going by means of periodic Texas legislative bailouts. After Prop. 1 passed, it was expected to bring TxDOT $1.7 billion a year in in new shale oil production tax money. Then the oil price collapsed in mid-2014, causing major TxDOT funding concern by the end of 2014.

State Rep. Joe Pickett, D-El Paso, sits on the Texas House transportation committee. He said lawmakers see the proposition’s 4-to-1 margin of victory as a mandate from voters to keep looking for ways to shore up transportation shortfalls. “It gives us the momentum,” he said. Pickett said top state officials, like Gov.-elect Greg Abbott, have mentioned making transportation funding a priority more often since Proposition 1’s passage than they did before the election. But Pickett also says that shoring up transportation funding — without raising taxes or creating budget holes elsewhere — will be a challenge.

Although TxDOT claims nearly $100 billion in assets (replacement cost of its roads), from a budgeting standpoint they should probably be regarded as an increasing maintenance liability headache. Since roads are maintenance money losers, trying to continually expand existing road capacity as a primary TxDOT goal results in costs that keep rising. These costs increasingly crowd new road construction out of the budget. TxDOT’s asphalt-paved roads, unlike many roads in Europe, are only designed to last about 20 years before needing major reconstruction.

This deficit should raise a red flag for city and county property owners.

The state policy of providing state road access to facilitate low density suburban sprawl development is, in effect a public subsidy for private land developers. Given land development friendly politics, this policy has tended to become an unfunded state-level mandate and an important reason why TxDOT is so deeply in debt, and why TxDOT is compelled to seek local funding from Austin and Travis county to widen IH-35. TxDOT has identified only about $300 million out of the roughly $4.5 billion needed, which leaves TxDOT about 90% short. In fact, the Travis County section of TxDOT’s My35 design is, by itself, $1.8 to $2.1 billion short. This deficit should raise a red flag for city and county property owners who may be scheduled for a big tax increase.

♦ November 2016 Austin transportation bond election: A rush job

Some local officials already seem to be on board supporting TxDOT’s plans to widen IH-35 in the name of relieving congestion. Austin’s influential state senator Kirk Watson has publicly registered approval for TXDOT’S IH-35 plans and seems to believe that it is possible for TxDOT to relieve IH-35 congestion by widening the road.

‘TxDOT targets I-35 in Austin for $158.6 million in congestion relief funding State’s most congested roadways to get $1.3 billion’

Relieving traffic congestion is essential for our economy and our quality of life,” state Sen. Kirk Watson, D-Austin, said in a news release. “I’m pleased this initiative has put the emphasis on I-35, which is the most pressing congestion problem for Central Texas as well as the state. We’ve worked hard and successfully to develop a plan for reducing congestion on I-35 and this investment is key to moving that plan forward.

Austin Mayor Steve Adler has been a proponent of a transportation bond election in November 2016, instead of waiting until the next bond election cycle in 2018. At a City Hall mini-press conference, Adler made the following remarks tied to IH-35:

We need to do some significant movement with respect to mobility and transportation in 2016… It wouldn’t surprise me if we weren’t coming to the voters in November with some capital expenditures associated with transportation. We know there have been some proposals with respect to I-35 that include increasing capacity that include putting in managed lanes so that we can have buses traveling at 45 miles per hour regardless of traffic so as to encourage people to get out of their cars, and depressing lanes so that (there is) a visual connection of the east and west sides of I-35. And I think there might be an opportunity to do something regionally in that respect. Why not try for that? There are also road corridors in the city that have gone through corridor studies… Lamar, Airport Boulevard, MLK, I think. People are looking for some movement on (Loop) 360 and other roads that are in the southwest and northwest. I would think that we need to take a really hard look at doing those things.

In addition, Austin Mayor Adler recently spoke to the Texas Transportation Commission about the necessity of dealing with IH-35 soon. Adler’s Facebook page says this about his comments to the Commission.

I-35 through downtown Austin is the most congested road in Texas. If we don’t do something big to fix this very soon, it’ll be the most congested road in the country. That is one list that we don’t want to be #1 on. This week I talked to the Texas Transportation Commission about how we can fix it.

Is a November 2016 bond election possible at this late date? Speaking to the Austin City Council February 3, 2016, Assistant Austin City Manager, Robert Goode, explained why speeding up a bond election for next November would be difficult at best.

Goode said there could be an “accelerated path” of 10 to 12 months, with the first two phases tightened up. But, remember, there are only nine months left until Nov. 8, and phase one hasn’t even begun. So Goode, cognizant that Mayor Steve Adler (with the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce nudging in the background) has been pushing to do something in November, offered one more timeline: the “aggressive path.”

A November 2016 Austin transportation bond election would greatly compress Austin’s existing bond review process. While everyone is clearly concerned about Austin’s severe traffic congestion, it is hard to understand how speeding up a transportation bond election would relieve traffic congestion faster, especially with regard to IH-35, and well before the IH-35 environmental reviews are finished. The November 2016 bond election seems to be largely focused on IH-35, which, as we have seen, cannot be “fixed” at any cost, if reducing congestion is the goal.

Politicians are already planning to add a lot more high density development along IH-35.

Despite this situation, politicians are already planning to add a lot more high density development along IH-35. Sen. Kirk Watson is a leading proponent of Central Health adding 3.7 million square, feet and 14.3 acres of new complex of high-rises in the area where the Erwin Center and Brackenridge Hospital are now. This plan was approved by Central Health in January, and is to start construction in 2017.

The Brackenridge Campus will connect the emerging University of Texas Medical District with the Texas State Capitol Complex, Downtown Austin, historic East Central Austin, Waterloo Park and the envisioned Innovation Zone. In 2017, Seton Healthcare Family will relocate UMCB hospital services from the Brackenridge Campus to a new teaching hospital, the Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas, adjacent to the Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin. The teaching hospital and medical school, both currently under construction, are located directly north of the Brackenridge Campus.

This medical complex development runs along IH-35 and Red River south of MLK. The proposed Dell Medical Complex is along IH-35 at one of the most congested corridors in Austin, an area that was once expected to be served by the light rail system which voters soundly rejected in November 2014. Could ambulances even get through to deliver medical patients for treatment at such a congested location?

With regard to the IH-35 capacity increasing projects, Austin officials should determine in advance how much money TxDOT expects from local sources. How much of the looming $4 billion IH-35 deficit Austin area taxpayers are expected to pay, and what will they see in benefits now that TxDOT is no longer willing to fund the roads that they are presumably responsible for maintaining. Tolled lanes on state roads are supposed to pay for themselves, so why would TxDOT ask Austin taxpayers to pay for them? Given the lack of congestion relief that CAMPO and TxDOT expect in return for spending lots of money on IH-35, Austin should seek clarity about the pros and cons of funding such projects.

TxDOT is planing to spend about $4.3-4.6 billion on IH-35 between San Marcos and Georgetown.

Many of the details on TxDOT’s plans for IH-35 were recently made clear when Austin’s new TxDOT District 14 engineer Terry McCoy explained to the Austin City Council Mobility Committee what TxDOT has planned for the Austin region of IH-35. TxDOT is planing to spend about $4.3-4.6 billion on IH-35 between San Marcos and Georgetown, upgrading this “most congested corridor” in Texas. Open this link and then open the clip for items “#7 & 8.” Go in about 24 minutes where you hear McCoy explain TxDOT’s plans for IH-35 in detail.

Congestion relief along IH-35 is conspicuously absent from road improvement goals that McCoy promises, but increasing road capacity is definitely a goal. The plan anticipates adding 35% of of new travel lane mile capacity to IH-35 between Georgetown and San Marcos, and over 50% in the central city area. There is talk of the close partnership between TxDOT and Austin. At about 35 minutes into the clip, there is a series of slides showing those parts of the IH-35 project that might be expected to start between 2016-2019, assuming that the money is there.

TxDOT’s plans along IH-35 appear to be a done deal and the three-county IH-35 project is not subject to much change, and the main variable seems to be how fast TxDOT can get the construction money. Assuming that there is a partnership between TxDOT and Austin, as McCoy and Assistant Austin city manager Robert Goode say there is, then TxDOT is the senior partner that gets to make the rules.

If Austin wants anything but the cheapest elevated-lane version of the TxDOT’s IH-35 capacity increase, the one option that TxDOT is willing to fund by itself, then sinking the road below grade and covering it over to make it less imposing is going to cost Austin a lot of money, which is presumably Austin bond money.

…One goal of the effort is to improve east-west connectivity across the thoroughfare in the urban core. The possibilities include intersection and access redesigns and adding bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure to cross the highway. “We’re adopting an ‘everything and the kitchen sink’ approach to I-35,” McCoy said. That includes either modifying the downtown section of I-35 along its current double-decker form or depressing all of the lanes, which would drop them below ground level. If city leaders and state transportation officials agree to lowering I-35, McCoy noted local funds could be used to then cover it up and put the new real estate to use in some way. “Once you depress the main lanes of I-35, then you have the potential to build caps. What you do with those cap sections is up to the locals,” he said. “But from TxDOT’s perspective…it is an amenity, so it would be a local cost item to pick up. TxDOT is essentially saying we cannot participate in the cost of constructing those caps.”…

It will take TxDOT another two years to get through the NEPA federal study process for the downtown section of IH-35. Depressing IH-35 through downtown as opposed to TxDOT’s cheaper design would cost about $300 million extra. Covering over the sunken road even more than that, but TxDOT won’t agree to pay for that.

Austin is running far behind in funding for its own transportation needs over the next 30 years.

Some things like the express lanes for buses on IH-35 that Adler mentions could not be implemented for about a decade, and must depend on a lot of public money from somewhere. According to Robert Goode in the same clip, Austin is running far behind in funding for its own transportation needs over the next 30 years, including a billion dollars just for sidewalks.

Rendering of proposed 6th Street Bridge, looking west, over a depressed IH-35. Image from Reconnect Austin.

♦ Shall the downtown section of IH-35 be depressed and covered?

As we have seen, TxDOT’s focus is nowadays centered on the addition of road capacity in an era of severely limited funds. In accord with this policy, TxDOT tends to define the improvement of IH-35 as squeezing the most vehicles onto this road at the lowest cost, which in a central city means elevated lanes to save on right-of-way acquisition costs. This is the case with IH-35 through downtown Austin. At the same time, TxDOT and the CTRMA are planning to use elevated lanes on MoPac South despite resistance from a coalition of environmental groups like the Save Our Springs Association. How to distribute the large amount of additional inbound commuter traffic coming from MoPac South into downtown Austin on Austin streets is an unresolved problem that the city of Austin left to deal with.

A cost-saving elevated road design on IH-35 means ignoring existing community plans which call for depressing and covering over the section of IH-35 that runs through downtown Austin, to give a less intrusive and imposing road impact. A smart growth-oriented architectural and planning coalition, ReconnectAustin.com, has been trying for years to get TxDOT to support a sunken road design that is covered over through central Austin, a plan developed and promoted by retired UT-Austin architecture professor Sinclair Black.

However, this is a road design which TxDOT considers a luxury compared to the cheaper alternative of adding more elevated lanes, In addition, there are complex and costly safety and engineering considerations, like ventilation, hazardous cargoes, and fires in the tunnel which TxDOT would rather not deal with.

Even when the IH-35 construction is completed, IH-35 will be a more frustrating and congested driving experience.

If there were ever an appropriate time to slow down and study the cost effectiveness of transportation alternatives, it is probably the example of what we should do about IH-35 and who should pay to do it. At the beginning of this essay, we have seen TTI explain why IH-35 cannot be fixed in any way that reduces congestion, no matter how much money is spend in the attempt. The widening would be very disruptive during the decade or more that TxDOT would need to do it, but even when the IH-35 construction is finally completed, IH-35 will be a more frustrating and congested driving experience than it is now. That should tell us that a new approach is needed, and Houston is trying to do that.

♦ Austin could choose its own future, as Houston is trying to do

Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner has recently told TxDOT that he wants to shift toward a transportation planning approach that makes better sense than TxDOT’s vision. Turner has taken the lead in calling for a big paradigm shift away from roads to a more affordable approach with a speech that he recently delivered in Austin.

We’re seeing clear evidence that the transportation strategies that the Houston region has looked to in the past are increasingly inadequate to sustain regional growth… The region’s primary transportation strategy in the past has been to add roadway capacity. While the region has increasingly offered greater options for multiple occupant vehicles and other transportation modes, much of the added capacity has been for single occupant vehicles as well… It’s easy to understand why. TxDOT has noted that 97% of the Texans currently drive a single occupancy vehicle for their daily trips. One could conclude that our agencies should therefore focus their resources to support these kinds of trips. However, this approach is actually exacerbating our congestion problems. We need a paradigm shift in order to achieve the kind of mobility outcomes we desire…

The Katy Freeway, or Interstate 10 west of Houston, is the widest freeway in the world, with up to 26 lanes including frontage road lanes. The 2008 widening had a significant impact on the adjacent businesses and communities. Yet, despite all these lanes, in 2015 the section of this freeway near Beltway 8 was identified as the 8th most congested roadway in the state. This was only 7 years after being reconstructed! This example, and many others in Houston and around the state, have clearly demonstrated that the traditional strategy of adding capacity, especially single occupant vehicle capacity on the periphery of our urban areas, exacerbates urban congestion problems. These types of projects are not creating the kind of vibrant, economically strong cities that we all desire.

Turner went on to make three recommendations:

We need a paradigm shift in how we prioritize mobility projects. Instead of enhancing service to the 97% of trips that are made by single occupant vehicles, TxDOT should prioritize projects that reduce that percentage below 97%. TxDOT should support urban areas by prioritizing projects that increase today’s 3% of non-SOV trips to 5%, 10%, 15% of trips and beyond. Experience shows that focusing on serving the 97% will exacerbate and prolong the congestion problems that urban areas experience. We need greater focus on intercity rail, regional rail, High Occupancy Vehicle facilities, Park and Rides, Transit Centers, and robust local transit. As we grow and densify, these modes are the future foundation of a successful urban mobility system. It’s all about providing transportation choices.

♦ What Austin does about IH-35 will determine what kind of city Austin becomes

The only real game changer for Austin is to take a new approach to land use planning and transportation such as Houston Mayor Turner is seeking. Truly cost-effective transportation requires integrating transportation planning with land use planning from the start, using tools like smart growth and transit-oriented development, strategies and disciplines which are known to maximize public mobility at a comparatively low cost.

Rail is the real way to unclog urban arteries.

Our travel demand models are probably inaccurate in assuming vehicle growth, whereas rail is the real way to unclog urban arteries. Thriving U.S. cities are increasingly congested with vehicle traffic, but preserving urban mobility depends on other factors like destination proximity and modal choice.

The Austin City Council Mobility Committee, chaired by Councilwoman Ann Kitchen, heard testimony on March 2 about what the city is doing in regard to its new transportation planning and finance. See clips 4 and 5.

‘Staff briefing on the Strategic Mobility Plan which will identify ways to improve efficiencies in our existing system, manage demand and strategically add capacity in all modes’

Clip 4 is particularly revealing because it describes the promise of a new two-year attempt to integrate transportation with land use planning, with lots of public input, as part of a new Austin Strategic Mobility Plan process scheduled from 2016-2018.

See slide 14, at about 15 minutes into the clip. This is a 10-year plan, to be updated every five years. There are a lot of optimistic sounding planning principles, and diagrams with boxes, but the specifics are yet to be determined. Here are the stages of the planned timeline:

2016 — “Getting the word out, Hiring a Consultant, and developing Visions and Goals

2017 — Analysis and Scenario Planning, Draft Network and Recommendations, Projects and Funding

2018 — Plan Adoption

There was a discussion about the creation of new Austin Street Impact Fees. Under state law, this revenue can only be used for street capacity increases, which we have already seen do not relieve congestion.

Haven’t we been through this before? In fact, this latest version of the Austin Strategic Mobility Plan is an update of what has been planned before.

The Austin Strategic Mobility Plan involved the analysis of City of Austin departmental and community input on mobility problems and priorities throughout the City of Austin. Projects have included roadway, transit, pedestrian and bicycle projects. The outcome of the preliminary stage of this work was a priority list of mobility CIP projects that were recommended and adopted for the City of Austin Bond Election in November 2010.

Later, as congestion continued to increase, Austin endorsed another new Austin Strategic Mobility Plan by a 7-0 vote in June 2014, on the urging of Mayor Lee Leffingwell.

“We have a serious mobility problem here. It threatens our economic development in the future, and it threatens our quality of life. It’s a big problem, and we need to have a big solution to it. We need to attack on all fronts,” said Leffingwell. The plan has not been funded. So if the item is passes, council will vote on Aug. 7 whether to put an item on the ballot to fund the plan in November.

This billion dollar bond package was voted down by a fairly wide margin in November 2014. One political mistake that the supporters of the November 2014 bond election made was to try to put a billion dollars of roads and rail into one giant bond package, all to be voted up or down. It was promoted by using a big advertising blitz to promote the whole package as a congestion cure by using clearly deceptive slogans; “With roads and rail we cannot fail,” and “Traffic bites, bite back.”

Why not give voters an intelligent choice that can stand on its merits.

Instead of treating voters as being too ignorant to know that there are no miraculous congestion cures, there could a real transportation bond choice that lets voters vote for what they want. For example, there could be a ballot proposal for a rail start, one for bikes, one for sidewalks, and perhaps one to eliminate road safety hazards. Why not give voters an intelligent choice that can stand on its merits, without claiming that any bond package centered on roads can relieve Austin congestion, especially while CAMPO and TxDOT are planning road projects that will make congestion steadily worse.

Whatever we end up doing about IH-35 in Austin will say a lot about what kind of city we want to become. Upgrading IH-35 capacity would eventually get more cars and trucks onto that road, but would not do that very fast and not without a lot of pain during a prolonged period of construction. Whatever we do on IH-35 will be hugely expensive, but it will make congestion worse, not better. Any benefits for transit, bike, and pedestrians as a side effect of IH-35 construction would be weak and incidental compared to direct strategic city spending on these alternative modes elsewhere.

Does everyone really believe that trying to increase IH-35 capacity should be a top regional transportation priority for Austin? Will some brave Austin area politician declare our highway policy independence from TxDOT, as Houston’s Mayor Turner did, and call for an Austin area policy shift away from TxDOT’s highway idolatry?

Additional money for the $4.5 billion My35 project looks like a slippery slope leading to endless TxDOT shortfalls and increasing local commitments. As they say, in for a penny, in for a pound. Eventually, after many years of construction disruption, IH-35 would carry more vehicles, but Austin congestion would be worse and Austin would be less affordable. Widening IH-35 would attract more cars and trucks onto IH-35 and thus facilitate a bit more sprawl development to serve new commuters living well outside the city and around satellite communities like San Marcos and Georgetown.

In fact, trying to help TxDOT widen IH-35 could easily use up ALL of Austin’s total high-rated bonding capacity and leave nothing for anything else for a long time, if that were our goal (this high grade credit availability was about a billion dollars in November 2014). Of course with billions in unmet Austin needs, we could also easily use up all of our high grade bond credit on widening city-funded arterial roads inside Austin. This would not reduce traffic congestion either, although this policy would tend to prevent a shift to transit-friendly development.

♦ The case for rail as soon as possible; we have already done the planning

If November 2016 is indeed an opportunity for putting mobility bonds on the November ballot, rail should be the top priority based on its merits and potential. The only really serious game changer is rail, together with a new commitment to a different kind of growth planning.

Winning a November rail vote would not be easy. First it is quite expensive, although not nearly so expensive as widening the roads like Lamar to try to achieve the same mobility along the same corridor. Second, rail can offer a very high and easily expanded corridor mobility, but only along one prime corridor, which must be very carefully chosen. (Capital Metro’s Red Line from Leander to the Convention Center was chosen because it was a sparsely used rail freight line that could be converted with federal funds, but not because its route was a good transit corridor.)

In the case of Austin, there is one corridor where the existing development is screaming for rail service, and that is the Guadalupe/North Lamar corridor. The Lamar-Guadalupe corridor runs between Austin’s two most congested roads, IH-35 and MoPac, which would help reinforce and complement the transit-friendly land uses which already exist in abundance along this corridor. In practice, such a rail corridor is typically linked with bus connections along the way, rather like ribs on a spine.

For a real central Austin mobility game changer along its best transit corridor, Austin needs a Guadalupe/North Lamar light rail line extending from downtown to some point past the North Lamar Transit Center. Light rail would reinforce and complement the transit-friendly land uses that have existed in this corridor since the days that streetcars served these same streets.

A new rail plan could be quickly assembled from at least four official past rail studies done on this corridor since 1984, the last, a full Preliminary Engineering/Draft Environmental Impact Statement from 2000. It could be done using the well-known competent national consult team, AECOM, already hired by Capital Metro to essentially study the same corridor. Urban rail in reserved lanes on the street could deliver 40,000 riders a day to and from the city core.

Experience elsewhere says that this modest start could over time generate billions of dollars worth of new tax base for an investment of less than a billion dollars, half of which could potentially come from the the feds. Compared to rebuilding IH-35 from Georgetown to San Marcos, a Guadalupe/North Lamar light rail project would be relatively simple and easy.

Light rail could be built on a relatively predictable schedule of less than five years, with a high potential for payback within a decade of opening, while setting the stage for more comprehensive public transit throughout the city and the region. What is now lacking is the political leadership to get it done. ♦

The author is no stranger to Texas road politics; here are some earlier Rag Blog posts by Roger Baker on the topic.

- “Austin : Where real estate drives the

political machine“ - “Texas Toll Road 183-A: The economics and the special interests“

- “Texas toll roads: Feds must take lead“

- “Is Austin drowning in traffic growth? Part 1)“

- “Transportation politics and the Austin road lobby (Part 2)“

Read more articles by Roger Baker on The Rag Blog.

[Roger Baker is a long time transportation-oriented environmental activist, an amateur energy-oriented economist, an amateur scientist and science writer, and a founding member of and an advisor to the Association for the Study of Peak Oil-USA. He is active in the Green Party and the ACLU, and is a director of the Save Our Springs Alliance and the Save Barton Creek Association in Austin. Mostly he enjoys being an irreverent policy wonk and writing irreverent wonkish articles for The Rag Blog. ]

According to the authors logic, if you are shopping in your local grocery store on the 4th of July and there is only one checkout lane open, then opening additional checkout lanes would not help you get checked out any faster. Just silly.

Such is the logic of liberal nonsense.

– Lance

Lance,

What Roger has cited here is well-established research showing that building new lanes only increases more traffic.

What is sad is that more conservatives do not understand that investments like rail are more efficient and sustainable ways to utilize the funds that we have, and not find ourselves into obscene amounts of debt, as TXDOT finds itself.

Why not an analogy with solar eclipses, or maybe, using cheese blintzes?

Effective analogy is an art — one you just flunked.

The “extra check out grocery lines” in your analogy are plausibly, rail. That’s a way to have that extra capacity when you need it and fit it into the crowded and expensive urban spaces.

That is the whole point of this piece, which you dismiss w/ an insipid one-liner.

You might try facts, logic, etc for your critique. But in Trump-land, you cuckoo birds are free to dwell, right? Who needs boring old facts and logic?

Lance,

Your analogy breaks down when you talk about demand. In a grocery store setting, more people are not going to suddenly surge into the store because two more check-out lanes are open.

That’s not the case with roads. It’s well-documented (and Roger provides the citation if you’d like to check it out) that building more roads and widening existing roads has a different effect – it actually increases demand. That “free” capacity that is suddenly available fills up in a shockingly short period of time, in exactly the opposite way that people don’t jump into their cars and head down to the HEB because there’s an additional check-out. The Katy Freeway example Roger gives is an apt one.

Lance analogy is sort of correct. Whether there are 5 lanes or 6 lanes traffic will continue to go at same or lower speed (congested). More output but not faster speeds/service.

The fun part and something folks have not explained yet is where will the extra lane of traffic will go? If going downtown, is there additional capacity from highway into downtown streets?

Roger Baker as usual bring extensive knowledge, experience, logic, and reason to bear on problems that others address with platitudes and easy avoidance.

But hasn’t Kirk Watson kind of always been a shill for TxDOT? Want to give us a quick review of his transportation leadership during his mayoral years?

Roger is a very smart guy I have no doubt. Far smarter than me I freely admit. But then again, this country has been run into the ground and brought to the precipice of darkness by very smart people, from both the left and the right.

Sometimes common sense is a better recipe (hey, that could be the theme for the 2016 election!) . There is a quote often credited to Mr Clemens (correctly or not) that figures don’t lie (checkout lanes) but liars do figure.

– Lance

Roger Baker’s magnum opus! It should be required reading for anyone in politics, transportation or finance. Those who take action to apply Baker’s wisdom will make Central Texas a better place–those who do the wrong thing anyhow will have a guilty conscience. This sword cuts either way.

If every time your Austin utility bill arrives, you say to yourself, “I’m really proud to be paying for the white elephant called Water Treatment Plant No. 4,” you’re really going to be proud when the bills arrive for the 2030 version of IH 35—a white mastodon.

I think the rail bond was voted down because there was no plan for rail on N to S Lamar. That is the most popular road in Austin, because it is the only north-south road aside from Mopac and I-35, and because so many popular businesses are located on or near it.

So any rail plan that does not figure out how to add rail to Lamar is going to fail, IMO. This article touched on it, but what really is a plan for this road? Elevated rail? That’s the only thing I can think of because isn’t digging a subway much too expensive because of the caliche rock here?

At any rate, I agree that expanding roadways ad infinitum just causes them to fill up faster, and that is not the solution.

The only solution I can see is rail, and that must include Lamar. So let’s figure out what to do there first.

The article substantiates that widening I-35 will greatly increase congestion, so light rail is the only reasonable solution to traffic gridlock. Such “widenings” and improvements to I-35 should only consist of numerous train stops with commuter parking lots situated on the outer edges of the city.

Lets see. On one hand will be a group trying to explain Roger’s reasoning (even a dumbed down version of it) to voters in a bond election. One the other hand will be a group shouting that the logic behind “building fewer lanes is somehow better than building more lanes” is just lunacy.

I know where my money will be.

– Lance

The chances of Austin voters being asked to go way into bond debt to “fix” IH-35 are realistically much greater than the likelihood of our politicians putting a serious rail proposal on the Nov. bond election.

I am only advocating what I consider to be a wise and visionary policy, while being fully aware of how myopic and anti-reform Tx state government can be, starting with the fact that TxDOT is typically run by rich political cronies appointed by the Governor and not experts.

Does Lance seriously think that TxDOT can keep borrowing money to build more lanes for roads — on top of its $20 billion in existing debt? How does Lance propose to raise the missing IH-35 widening money, through tolls or higher taxes?

I had a wonderful and highly paying job on the 23rd floor of a building in the heart of downtown Austin. But the price i paid for that job was about 2 hours a day of my life spent in a car. I decided that I either had to live closer to where I work or work closer to where I live. So i gave notice, even before securing another position and never looked back. There is nothing in downtown Austin that I cant live without. Austin culture and politics are not mine.

To be honest, I could care less how congested downtown traffic gets or how miserable the commute is. My solution is to do nothing and let the people who live and work in downtown Austin stew in their own “smart cities” broth. Maybe more of them will make the choice I made and voluntarily take a car off IH35.

So clearly I do not have a dog in the fight. But I think the chances of the “sound-bite” voters picking up what Roger is putting down is very low. I do appreciate his thought leadership and his planning. But other than the audience here and the elitist intellectuals in Austin who are already convinced, I don’t imagine many Austin voters are going to even get his argument let alone vote to spend money NOT to build more lanes.

– Lance