The next global crisis:

Will ‘peak food’ follow ‘peak oil’?

By Roger Baker / The Rag Blog / September 23, 2010

Will we soon experience a global peak in food production, similar to peak oil?

It is too difficult and too soon to predict a global peak in world food production, but it is easy to see that some such event cannot be delayed much longer, and is quite likely to occur within the next five years. This despite the fact that global grain reserves seem to be adequate for now.

The World Bank writes that “it is too early to make conclusive statements on the impact of the very recent global wheat price spikes at the national and household level.” The FAO has likewise stated that there does not currently appear to be a crisis, but that it is concerned about the amount of volatility in food markets. And that volatility might bode ill for progress toward overcoming challenges like those laid out in the Millennium Development Goals being discussed at the U.N. this week.

“These recent global staple price increases raise the risk of domestic food price spikes in low income countries and its consequent impacts on poverty, hunger and other human development goals,” according to the Bank.

Peak food is pretty hard to determine compared to peak oil, partly since so much of its production is local. Global food demand can restructure in its demand over time to accommodate a reduction in food supply. Those who are hungry will tend to shift their consumption to cheaper calories, often at the expense of its nutritional content. Globally, the wealthier tend to favor animal protein produced from grain, foods imported from afar, and in general less energy efficient foods.

Grains are the most important global food commodities to focus on because they provide such a large percentage of the world’s total food calories, and because they can be stored and traded to reduce local food shortages. Wheat and rice are the top human food grains by tonnage. Other commonly used animal feed grains like corn are termed coarse grains. Wheat tends to be more used globally to prevent regional hunger, whereas rice provides cheaper food calories but is more often produced and consumed locally.

Since food is so vital for survival, those who are hungry will try to shift their spending to food if they are able. Intensive urban or backyard agriculture can help some. The suburbs of today may be the produce gardens of tomorrow. If animals are fed less, then humans can eat considerably more. Biofuels like corn ethanol are mostly an energy waste, so that in response to high fuel prices, food can probably outbid biofuel production in competition for arable cropland.

The economics of the food marketplace is obviously a lot different for affluent countries when compared to poor countries struggling to feed themselves. If food prices rise, the world’s affluent can eat less beef in exchange for eating more of the the corn previously fed to the cow. However, many of the world’s poor may already spend a lot of their total income on grain, or they may suffer from local production crises complicated by poor transportation, as is the case with Pakistan. Localized food shortages are likely to increase.

The big picture in terms of global food production is that the healthy survival of adults requires about 2,500 food calories per day for each person, in order to feed roughly 6.8 billion people. Since global population is increasing at about 1.17% per year, this means food production needs to increase accordingly to hold food prices constant, assuming the same food production and consumption patterns.

The global food production trends

are moving in the wrong direction

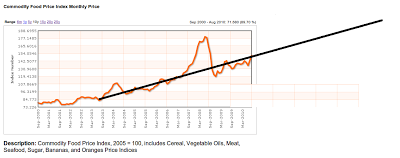

Looking at this food price chart (below), over the span of about a decade we see a trend line increase of over 10 percent per year.

CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE

If we ignore the late 2007 to early 2009 price spike and the brief below the trend line decline, we see a recent return to the long range upwards trend. We need to examine the various factors that affect the global food price index, and how they are likely to influence the total average cost of food.

If we extend the 10 percent yearly food price index increase trend line, we find that the previous price pain level is likely to be reached again by about 2014. We might anticipate about the same unhappy result if average food costs reach the 2008 peak while average earnings remain stagnant. This situation was painful enough to cause food riots in about 30 countries around the world, as well as encouraging speculation in food commodities.

The immediate causes of the protests in Mozambique’s capital, Maputo, and Chimoio about 500 miles north, are a 30% price increase for bread, compounding a recent double-digit increase for water and energy. When nearly three-quarters of the household budget is spent on food, that’s a hike few Mozambicans can afford.

Deeper reasons for Mozambique’s price hike can be found a continent away. Wheat prices have soared on global markets over the summer in large part because Russia,the world’s third largest exporter, has suffered catastrophic fires in its main production areas. These blazes, in turn, find their origin both in poor firefighting infrastructure and Russia’s worst heatwave in over a century. On Thursday, Vladimir Putin extended an export ban in response to a new wave of wildfires in its grain belt, sending further signals to the markets that Russian wheat wouldn’t be available outside the country. With Mozambique importing over 60% of the wheat its people needs, the country has been held hostage by international markets.

This may sound familiar. In 2008, the prices of oil, wheat, corn and rice peaked on international markets — corn prices almost tripled between 2005-2008. In the process, dozens of food-importing countries experienced food riots…

Dr. Tad Patzek is Chairman of the Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering Department at The University of Texas at Austin. Besides working on fossil fuels, Patzek is studying the thermodynamics and ecology of human survival, and the food and energy supply for humanity. He spoke at a September 14 meeting of the Austin Sierra Club and provided the following abstract of some of his studies on food crops, which indicate that per capita food production is likely already peaking:

The main staples I have looked at are wheat, rice, barley, potatoes, and rye. The world’s production of these staples is not keeping up with population growth. Their production is stagnant or declining, and crop areas are declining. Per capita production (kg per person) and per capita yield (kg per person per ha) are declining.

We are witnessing a global failure of modern food supply and inflation of food prices. This inflation became hyperinflation in 2007 and 2008, because of the massive, destructive speculation on wheat and other staple futures by Goldman Sachs and international investors.

The main energy crops I have looked at are maize, sugarcane, soybeans, and oil palms. The world’s production of these crops is rapidly expanding. Their crop areas are increasing (exponentially for soybeans and oil palms in the tropics). Per capita production is increasing, but per capita yields are declining. We are witnessing a global move away from food to energy crops. Diverting more land to pure energy crops, switchgrass, etc., will only deepen the food supply crisis, especially in the poorest countries.

Genetically modified plants, while easier to grow, and very profitable for the seed manufacturers, create problems with yields, water, and fertilizer requirements, and cause a fast-spreading resistance of weeds and pests. So, is there a solution? Perhaps, but it would require a change in the current paradigm of industrial agriculture.

What causes food prices to rise?

How do we explain the steady upwards food price trend and then the sudden spike and decline in 2007-2009? I believe there are three basic and somewhat interacting factors at play.

The first factor is the declining per capita food production discussed above. It is primarily this factor that causes the steady upward trend line. If per capita food production is really decreasing, it could hardly be otherwise. The other two important factors are peak oil, and finally, food market speculation.

When we try to discount the early 2008 food price spike tied to oil oil costs, and to speculation, we see the longer term food price index rise of more than 10 percent a year. This trend line looks like it will intersect its previous price 2008 peak before 2014, if not before.

Since the last few years have been a period of global recession, we can probably assume that average global per capita purchasing power for food has been been almost flat during the last three years, as it has been in the USA. Furthermore, we can probably anticipate that given a globally depressed economy, there is scant prospect for a real earnings increase in the near future.

It makes sense to imagine that over a period on the order of a decade, and discounting speculation, the various roughly linear factors like population increase, global warming, water constraints, urbanization of arable land, and rising energy price increases will continue to work together to restrain an increase in the global food supply.

The rise in food prices has a natural component related to its steadily rising difficulty of production in the face of increasing demand. The steady component of the rise in the food index increase is due to the combined effects of these factors, well outlined here.

Nomura Group is confident that this is a long-term macro trend that will continue in the years ahead:

We expect another multi-year food price rise, partly because of burgeoning demand from the world’s rapidly developing — and most populated — economies, where diets are changing towards a higher calorie intake. We believe that most models significantly underestimate future food demand as they fail to take into account the wide income inequality in developing economies.

The supply side of the food equation is being constrained by diminishing agricultural productivity gains and competing use of available land due to rising trends of urbanization and industrialization, while supply has also become more uncertain due to greater use of biofuels, global warming and increasing water scarcity.

Feedback loops also seem to have become more powerful: the increasing dual causation between energy prices and food prices, and at least some evidence that the 2007-08 food price boom was exacerbated by trade protectionism and market speculation…

Meanwhile, global warming is lowering food production and raising food prices in a way that can be roughly quantified on average, though it is seen locally as an unpredictable increase in weather volatility like droughts, floods, and heat waves:

The two scientists analyzed six of the most widely grown crops in the world — wheat, rice, maize, soybeans, barley and sorghum. Production of these crops accounts for more than 40 per cent of the land in the world used for crops, 55 per cent of the non-meat calories in food and more than 70 per cent of animal feed.

They also analyzed rainfall and average temperatures for the major growing regions and compared them against the crop yield figures of the Food and Agriculture Organization for the period 1961 to 2002.

“To do this, we assumed that farmers have not yet adapted to climate change, for example by selecting new crop varieties to deal with climate change,” Dr Lobell said.

“If they have been adapting, something that is very difficult to measure, then the effects of warming may have been lower,” he said.

The study revealed a simple relationship between temperature and crop yields, with a fall of between 3 and 5 per cent for every 0.5C increase in average temperatures, the scientists said…

The looming wild card:

How peak oil can spike food prices

Peak oil is already a serious problem that affects food prices in many ways. Parts of the slowly depleting Ogallala Aquifer in the U.S. Midwest have been so heavily pumped so far below the ground level, that the rising cost of diesel fuel to pump aquifer water up to the surface has eliminated the profit to be made on the irrigated crops.

The food price index has a strong tendency to echo the price of petroleum, in common with many other traded commodities. Global oil prices are currently fluctuating within a band of about $70-$80 a barrel, held down for now largely by a depressed world economy.

A major oil price increase is also partly being restrained by the buffering effect of the untapped reserve capacity of OPEC, estimated at about 5 million barrels per day.This reserve capacity is mostly within Saudi Arabia, which is suspected of exaggerating this reserve capacity.

We are already well past a global peak in conventional oil production on dry land. Oil is getting harder and harder to produce. If we are not yet peaking in liquid fuel production, we are probably within five years of such a peak in all liquid fuels. These fuels are vital for portable power and transportation needed for food production and distribution. Robert Hirsch is a top oil analyst who argues that the politicians who understand the energy situation are mostly unwilling to discuss the true implications publicly.

Since food production and distribution are both energy intensive, any return of the 2008 oil price spike would necessarily be soon reflected in another spike in global food prices. With the end of an undulating global oil production plateau we have been experiencing since 2004, and facing a significant decline in liquid fuel production, we face a steep increase in the cost of fuel embedded in the price of food. Another oil price spike is nearly certain to bring in its wake another food price spike, and the return of widespread hunger and political unrest.

The threat of another food speculation bubble

Even if we could somehow assume perfectly ample supplies of liquid fuel, the trend line shows that various other factors inhibiting food production increases are probably enough to cause the return of a food price crisis widely felt by about 2014.

Such an increase is likely to encourage some nations to stockpile reserves of their national production. This may be quite rational given the key importance of food security to national economies, but it would also tend to encourage the return of global food speculation. We can see the speculative bubble in the sharp food price rise above and subsequent fall beneath the trend line, during the period from 2007-2009.

The exponential food price rise seen during 2007 seems to be a speculative bubble because it soars far above the decade long trend line before collapsing. Part of this sudden price increase was due to rising oil price, and some was due to food market speculation.

We now know that Goldman Sachs and others were strongly involved in food price speculation, anticipating profit from a sharp rise in food price:

In early 2008, everything boiled to the surface. The banks were fueling this artificial demand, and speculation drove wheat prices out of control. This spurred riots in more than thirty countries and drove the world’s food insecure to over one billion people. Somehow, this so-called fabulous investment was causing some serious trouble…

This far away world of high finance and commodities trading impacted the price of bread, cooking oil, butter, and other items all over the world. This is when the price of food gets scary — it’s as if the masters of high finance have the ability to reach down and take the food right off of the tables of the poor. For most of the readers of this blog, you are maybe spending 15 or 20% of your income on food. But most people on this planet are spending upwards of 50% of their daily earnings on food. For many, the food bubble pushed that up to 80%, and right into the arms of food insecurity, malnutrition, and starvation…

Food reserves have always been by nature conducive to hedging, hoarding, and speculation. Countries that experience shortages tend to try to secure food reserves in advance. Russia is now embargoing its wheat, which is raising its price globally. A rise in price tends to encourage further speculation.

Food is naturally and historically conducive to stockpiling reserves in anticipation of possible crop failure. If the price of a basic food crop rises, there is a natural tendency to buy some in reserve, which then causes the price to rise further.

This may be rational behavior for individuals, who may decide to stockpile a few months supply of grain for their family. However if this difficult-to-control behavior becomes widely practiced, it can easily lead to serious food shortages becoming a lot worse, which in turn is likely to force food rationing, other than by price.

[Roger Baker is a long time transportation-oriented environmental activist, an amateur energy-oriented economist, an amateur scientist and science writer, and a founding member of and an advisor to the Association for the Study of Peak Oil-USA. He is active in the Green Party and the ACLU, and is a director of the Save Our Springs Association and the Save Barton Creek Association in Austin. Mostly he enjoys being an irreverent policy wonk and writing irreverent wonkish articles for The Rag Blog.]

Hempseed, the most nutritious foodsource on the planet, can keep us from the scenario of “peak food” as it could from the scenario of “peak oil”.

This valuable, renewable resource has been stolen from us by our corporate masters.

Hempseed has more protein than beef,and a complete protein at that, rare in plant foods. A serving contains a day’s worth of essential fatty acids, called “essential” because they are necessary for human life. There are vitamins, minerals, and even dietary fiber for those who eat the crunchy hulls.

In addition, hempseed is delicious, and a versatile cooking ingredient. Once consumed worldwide, we’ve forgotten one of the first plants ever cultivated for food.

In response to the comment about hemp:

1. Much of the information is true and correct. E.g. hemp is kept from us by OCM, hemp is yummy & nutricious, we should be growing hemp, et cetera …

2. Hemp can not solve the related peak oil or peak food issues. Note that these are predicaments, not just problems. Thus, they can not be ‘solved’, only coped with. Once centralized control breaks down (a bad thing, no matter how one may feel about those with control) then communities would be very wise to grow hemp, to help mitigate local effects of global food and energy decline.

Bruce in Oregon

Mariann;

You are right on!

Cannabis, Hemp, Hops; they are the real deal in medicinal and flavor plants.

Also useful as an industrial fiber; clothing, ropes all sorts of things.

All the best,

mps

Correction accepted, Emergyscholar; real solutions will only come from new attitudes about energy and hundreds of things like co-generation, more efficient fuels, much wider use of renewable energy etc. And food isn’t simple either, as Roger discusses in such detail.

But if progressive people continue to ignore the very real and quantifiable benefits that cannabis could bring to both the energy and looming food crisis, or continue to relegate it to the back burner of issues to be addressed NOW, we do a very real disservice to the causes we seek to champion.

The drug war propagators have done excellent work in convincing far too many activists that cannabis isn’t an important issue. As a result, the legalization movement is substantially weakened by many problems that could be addressed by seasoned activists; the almost total lack of female leadership at a national or even state level in legalization groups is only the tip of the iceberg. But activists fear being trivialized at best, criminalized at worst, if they get involved in the struggle to end hemp prohibition.

Medical cannabis I consider a battle nearly won, with approval in, I think it’s now 14 states and the District of Colombia, and more ballot victories expected this fall, and mounting scientific evidence (and Big Pharma interest!) as clinical testing is finally being allowed, a little bit, in the US, and progressing rapidly in Israel, Brazil, and the UK. But we are still blind to the real reason why “marihuana” was made illegal in 1937; still think it has to do with the government giving a damn if you mess up your brane cells; still haven’t learned to FOLLOW THE DOLLAR for knowledge and wisdom. Ask, “Who profits?” and achieve satori!

The other tragic mistake in food production was to take it away from the local people, sending them off the land and into the factories, and linking food to dollars. President Clinton recently apologized for his role in this policy. The most efficient use of the land is small farms, and the smaller, the more productive.