Shredding the envelope:

Healthcare on the ground – Part III:

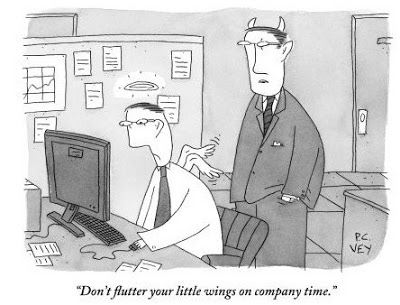

The anti-angel forces

By Sarito Carol Neiman / The Rag Blog / September 22, 2011

[Shredding the Envelope (“Ruminations on news, taboos, and space beyond time”) is Sarito Carol Neiman’s (occasionally) regular column for The Rag Blog. This is the third in a series. Read Part I here.]

The computer workstation in my dad’s room, according to the sales pitches of companies who sell them, was designed with the best of intentions to improve both the efficiency and quality of care in hospitals.

It would allow Dad’s caretakers to enter the latest information about his care (vital signs taken, medications given, observations observed) and to retrieve any information about him and his condition they might need — on the spot, without having to go and fetch it from (or take it to) its central location at the nursing station down the hall.

It would allow them (in theory) to spend a little extra time in the rooms with the patients, as they entered or retrieved their information — assuming they could safely mix “quality time” with the patient and the entry/retrieval of complex data at the same time. (An assumption of multitasking ability whose superhuman dimensions the sales pitches overlook.)

In theory, this computer workstation could be part of a vast network of computers, consolidating input gathered from every healthcare professional who had ever seen my dad for any reason. It could offer a more comprehensive picture of Dad’s medical history and current condition than any single human could possibly manage.

Imagine the possibilities… if such a network had been in place from the beginning of this years-long saga, and if all the professionals involved in Dad’s care had been doing more than just their jobs, he very likely would never have ended up in the hospital in the first place.

Those are some pretty hefty “ifs.” And as good a starting point as any to take a look at the “anti-angel forces” at work in the U.S. healthcare system.

Let’s take care of the big stuff first. Let’s assume that our “inalienable rights” to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness include the right to healthcare — not as a consequence of having the money to pay the going market rates for it, but as a consequence of being human. Let’s assume, in other words, that there is no need for private insurance companies, hence no fear that a person’s medical history will be used to deny coverage, or to charge an arm and a leg for it.

Let’s further assume that we can agree that being a healthcare provider is a very special calling indeed, and that those who take up the calling should be honored and rewarded for making that choice, rather than being thrust into indentured servitude by a mountain of postgraduate debt, forced to pay for that debt by performing procedures rather than spending time with and understanding their patients, and being stalked by “ambulance-chasing” lawyers whose primary motive is to make a buck on their mistakes and on the suffering of the victims of those mistakes.

(More about the whole “tort reform”/malpractice thing at another time.)

So now we’ve taken care of the big stuff, we get to the sticky, non-systemic, human bits.

Of course, a universal “inalienable right” to healthcare would need us all — hospital administrators, doctors, nurses, aides, and patients, all of us — to behave sensibly, like grown-ups.

We would understand that sometimes things get broken and can’t be fixed, and not every mistake is the result of malice or incompetence. We would know the futility, even harmfulness, of squandering scarce resources on experimental fixes that are likely to fail, or only extend suffering rather than heal. We would understand that death is a natural and inevitable part of the continuum of life.

We would do our very best to keep ourselves healthy and, when those efforts fail, do our best to comprehend the reasons and take responsibility for whatever part we might play in getting better. We would know when to push on against all odds, and when to call it quits. We would celebrate every small victory, and we would know when to allow ourselves to grieve.

We would, in other words, be able to see every health crisis for the opportunity it brings — to take stock of our priorities, to allow ourselves to love and be loved, to heal the old and untended wounds that so often seem to surface at these times.

To help us get from here to there, though (it’s unlikely we’re just going to wake up and find ourselves there), we’d have to start with a clear-eyed look at what we’ve got now.

The computer workstation in my dad’s room, attached conveniently out of the way on the wall, was a neutral presence, at first glance. And, as advertised, it was undoubtedly a time-saving, mistake-reducing tool. It wasn’t until it broke down for a few days that I began to understand how it was also being used by “anti-angel” forces.

As long as this tool was functioning, nurses came and went with their tasks-to-perform and medications-to-give on what was apparently a rigid, inflexible schedule. It didn’t matter whether Dad was eating his breakfast, having a phone conversation with a loved one, or peacefully asleep — the pills had to be given, the BP cuff strapped on, the thermometer inserted. Toward the end of his stay, when he was better able to move around, he discovered that the only way to assert his right to uninterrupted peace and quiet was to go and sit on the toilet.

When the computer workstation tool stopped functioning (and I confess to an irrational fear that I might be blowing the cover of a complex angel-conspiracy) somehow it became fine to let Dad finish his breakfast, or his phone call. To come back a few minutes later to do whatever was on the nursing agenda to be done. Not a problem, said the gracious smiles and body language of the nurses carrying the pills and thermometers. I’ll come back in a little while when you’re done.

And they didn’t forget, either — it wasn’t as though these important tasks magically disappeared from the “do-list” just for lack of computer assistance.

That’s when it occurred to me that behind the hunched shoulders and grim determination of nursing “business as usual” was a Big Brother element that the nurses were fully aware of, but the workstation sales pitches don’t mention. A function more interesting to hospital administrators and lawyers, say, than to doctors or other actual hands-on providers of Dad’s care.

It works like this: the nurse turns on the computer and scans in her badge (nurse presence accounted for) at a certain time (schedule adhered to and trackable by the minute) followed by scans of medication labels, or keystroke entries of vital signs (asses covered). Checked off the list, tidy and impersonal, easily scanned by those whose interest is that no unpredictable breezes of individual human needs or circumstance should interfere with the hum of the well-oiled (and litigation-protected) hospital machine.

The doctors didn’t have to use this workstation, however. They could, if they wanted to look something up… but they didn’t have to, nor did they have to tell it whatever it was they did while they were there.

My sense was that the whole workstation set-up not only reflects but also reinforces the subordinate and purely functional role of nurses in the system as it is. In most hospitals — with a few notable exceptions, I have heard — nurses are told what to do (“doctor’s orders”), expected to pass along requests or problems from the patients, and rarely if ever encouraged (or even allowed) to express an opinion, make a recommendation, or question a decision by the doctor that their best intelligence tells them might not be a good idea. A bit silly, to put a better face on it than it deserves — given that the nurses spend far more time with patients on an hour-by-hour basis than any doctor can possibly afford to spend.

It also, of course, reflects the fact that as the system is set up now, the actions of doctors and the reasons behind those actions are largely protected from public view, and are not required to be shared with other members of the team unless the doctor chooses to share them.

Doctors.

When I first met Dad’s surgeon, I didn’t like him much. Not because I thought he was incompetent — on the contrary, I was satisfied that he was the best available anywhere near Dad’s home. My dislike was more in the realm of “bedside manner.”

I can’t really blame him for the fact that at our first meeting he was uninterested in knowing who I was or why I was there, to the point of being dismissive. He had, after all, already met and spoken with several members of the family along the way, and at that point I must have seemed like yet another potential burden of irrelevant and time-consuming human interaction that he would just as soon avoid.

Plus, he’s a surgeon after all, not a GP — the skill sets required to do an excellent job in those two realms are different. Even if the skills to do more than the job might overlap or even be the same.

Over subsequent meetings our relationship was rocky, with additions of ego-prickliness alongside any deficits in bedside-manner skills. He didn’t like being questioned, especially in front of his entourage. This dislike, it seemed to me, carried the weight of a reflexive assumption that my questions were posed as a challenge, rather than as a sincere effort to understand.

I did my best to accommodate the lesser angels of his nature, to reassure him that I absolutely trusted his medical expertise, while still honoring my own concerns for the rocky spots in Dad’s recovery and whatever support I might be able to lend as a “person on the ground.” In the end, I didn’t want him to change, really — I thought he could use a good “right-hand” person, more a GP type, whom he trusted and who trusted him, to take care of the squishy bits of listening patiently and explaining things to people like me, and maybe translating my concerns into a language he could better understand and relate to.

We worked it out, somehow — the mutual respect and understanding between him and Dad was undisturbed, and when he finally came in with the happy news that Dad could leave the hospital and go on to the next stage of getting strong enough to go home, I was as fully included in the sharing of that news as was appropriate, given who was most directly affected.

I was also delighted to hear that during Dad’s recent follow-up visit, the doctor showed him “before and after” X-rays of his lung, and the transformation that had taken place. The news nicely balanced what happened that day when Dad was having such a hard time, convinced he wasn’t getting any better and grumbling about having to go downstairs for a new X-ray every morning.

When the doctor came by, I suggested maybe Dad could see a before-and-after picture, so he could look for himself how things were going. The response was a little explosion of exasperated breath, an energetic (if not physical) throwing up of the hands, and a “that’s not so easy, it’s all on computer” before turning around and (energetically) stomping out the door.

I liked it when I heard the news that the doctor had managed that “show and tell” … because I know it helped Dad, as it would have helped him on that day I suggested it in the hospital, to get a handle on whether the whole ordeal had really been worth it. Maybe, I thought, just maybe he had heard me after all. Maybe he’ll remember it the next time one of his patients is having a hard time convincing himself it’s all worth it.

We all have a lot of work to do if we are going to meet the challenges of providing thoughtful, competent, whole-person healthcare in this world.

We’ll have to figure out the best ways to weed out those who are thoughtless and incompetent and in jobs they aren’t suited for. And we’ll have to work on minimizing the harm done by our natural human tendencies to want magic pills, and to substitute a messy and mysterious wholeness with discrete and manageable, but lifeless, parts.

We’ll need to figure out how to shift our focus from avoiding the worst to striving for the best.

We’ll have to take a deep look at the role of lawyers in the healthcare system, and the hopeless, despairing greediness they so often foster in our lives. We’ll need to acknowledge that no amount of money can alleviate pain and suffering, and that often, all any of us really wants is a heartfelt apology, shared grief, and support for moving through a loss. And yes, too, sometimes, the satisfaction of knowing that an incompetent, greedy, or careless practitioner will never be able to harm anyone again.

It’s a lot of work, and it needs us all to do more than just our jobs. And at the moment, for me, it’s right up there among the top jobs on the list of those most important and meaningful.

[Sarito Carol Neiman (then just “Carol”) was a founding editor of The Rag in 1966 Austin, and later edited New Left Notes, the national newspaper of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). With then-husband Greg Calvert, Neiman co-authored one of the seminal books of the New Left era, A Disrupted History: The New Left and the New Capitalism and later compiled and edited the contemporary Buddhist mystic Osho’s posthumous Authobiography of a Spiritually Incorrect Mystic. Neiman, also an actress and stage director, currently lives in Junction, Texas. Read more articles by Sarito Carol Neiman on The Rag Blog]

- Read “Healthcare on the Ground, Part I” by Sarito Carol Neiman / The Rag Blog / Sept. 1, 2011

- Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s July 29, 2011, Rag Radio interview with Sarito Carol Neiman.

Good series. Thanks!

It is also helpful to good infrastructure of hospital so it is easy and helpful to do work. If is divided and get good management so it also handle to patient.