An Idiot’s Guide to Myth-Busting

By Sid Eschenbach / The Rag Blog / April 19, 2009

All things come to an end, and this deep recession will not be the exception no matter what policy roads are taken. However, the speed with which we are able to climb out of the hole and the shape of the economy once out depend directly upon our understanding of what happened … of how, exactly, we got here.

The answer to those questions lies in what economic theories we hold as truths and upon which we shape the policies that lead us forwards, and which theories we discard as false as we rebuild on the ruins of the present. Will they be the theories of the past 30 years, of laissez faire capitalism, low taxes, inequality, deregulation, free trade and the celebration of greed; or will they be the theories of the 50 years prior to that, the theories that brought us the great middle class, social security, economic stability, progressive taxation and general equality?

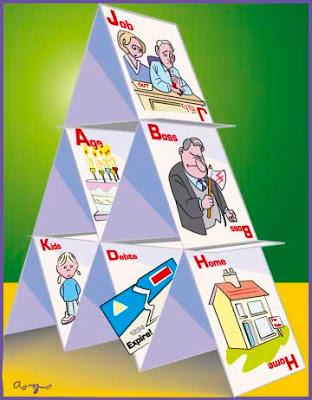

To inform that outcome, we need to look closely at two particularly pernicious central myths of Free Market theology:

- Low taxes stimulate and grow the economy

- Import duties and tariffs inhibit trade and shrink the economy

While the larger body of laissez faire capitalistic theory includes many other dangerous moving parts, these two are central to the disaster we are currently trying to manage, and refuting and burying them is essential to our thinking clearly about our way forwards and our ability to shape rationally what we want ‘recovery’ to look like. To do that, let’s examine each more closely:

Myth #1: Lower taxes stimulate and grow the economy, while higher taxes choke and slow the growth of the economy.

When economists talk about ‘stimulating’ an economy, they are essentially talking about injecting capital into the system through one means or another (either via internal or external mechanisms), thereby creating new money … and (at the risk of inflation) the economy ‘grows’. Historically, this was done ‘internally’, first through trade and then through manufacturing, as those activities created money through profits. In trade, it was buy low, sell high, and then spend, save or reinvest the ‘value added’. In manufacturing, it was buy raw materials, sell finished goods, and then spend, save or reinvest the ‘value added’.

Both of these natural capitalistic activities reliably produced economic growth and wealth over the centuries, from Carthage to Venice, from Beijing to Amsterdam. However, since the advent of central banks and the creation of financial markets in the 18th century, there have evolved a variety of new ‘external’ ways an economy can be ‘stimulated’ that are now standard tools of economic policy.

A review of the methodology of ‘stimulation’:

- First, as mentioned above, money can be created through trade, buying low and selling high, creating new wealth.

- Second, money can also be created through ‘value-added’ manufacturing activities that create a new finished item, the value of which is greater than the sum of the component parts.

- Third, money can be ‘created’ by simply speeding up the velocity of spending. This increased rate of spending has essentially the same effect as adding money to the system.

- Fourth, money can be created through commercial (non governmental) debt, thereby increasing the total amount in circulation and ‘stimulating’ the economy. Obviously, the greater the amount of leverage permitted the lenders, the greater the ‘stimulation’.

- Last, central governments can create more money through either issuing instruments of government debt or simply by printing more money, thereby ‘stimulating’ the economy.

It might be noticed that none of those examples of the different ways to stimulate an economy mentions tax cuts… and that is for the simple reason tax cuts per se are no more stimulative that regular income, and regular income is not considered ‘stimulative’ by economists. A tax cut is simply a transfer of capital out of public and into private hands… without the creation of any new capital, and therefore, in ‘simulative’ terms, there is absolutely nothing intrinsically stimulative about a tax cut.

What do the Stats Guys Say?

If taxes paid to the government disappeared in smoke, burned at the feet of some bureaucratic idol, then in comparison, a tax cut would be stimulative… but that of course is not the case. Government revenues have many destinations, just as do private, and as they are both distributed over a wide variety of consumption, savings, operating expenses, investments, etc, it is very difficult to argue that there is a clear ‘stimulus’ created by either… and it is why ordinary income is not considered a ‘stimulus’ to the economy.

Mark Zandi, chief economist and founder of Moody’s Economy.com, and the CEPR (Center for Economic Policy and Research) have both demonstrated that the opposite is actually the case… that government spending is more ‘stimulative’ than private spending (via tax cuts). Specifically, tax cuts generate .30 to .50 cents of ‘stimulus’ for every dollar ‘cut’, while government spending generates from $1.38 to $1.73 of ‘stimulus’ for every dollar spent. What that means is that government spending is approximately 4 times as ‘stimulative’ as a tax cut.

However, as the ‘stimulative’ effects of both tax cuts or increased government spending are, in normal economic circumstances, relatively small compared to true economic stimulus… like monetary growth through central bank credit, the value added profits generated through normal industry, or the impact upon an economy of the creation of entire new industries (like the tech revolution of the 1990’s), neither is considered nor should it be considered ‘stimulative’ in the macro sense.

Destination is Important

Where there is a real difference between the economic effects of tax cuts vs. government spending is not how much they ‘stimulate’, but where they ‘stimulate’… what each spends their money on and the long term effects of that spending… and that bears directly upon the discussion of what kind of economy needs to be built out of the ruins of the laissez faire experiment.

National, regional and local governments, through large scale spending and long term investment, are able to create many essential things that private individuals are simply not able to… like health and education systems, transport and communication systems, security and judicial systems… all of which are investments that are essential to create the framework within which individuals and companies then do their part, within the capitalist system, and create new trading and manufacturing value added activities that are beneficial to the wellbeing of society at large.

Individual tax cuts cannot begin to have this kind of impact, and as shown by the return on investment numbers above, the reality is that they cannot begin to have the impact upon the national economy that government spending does. Therefore, a government that spends wisely can have a broad, beneficial and enduring impact on the society at large. For these reasons, much more than for their larger ‘stimulative’ effects, government spending well applied can be much more beneficial to the national economy than individual tax cuts.

Prosperity AND High Tax Rates?

The best example to prove the veracity of all of the above, of course, is the period at the end of the Great Depression. During and for many years after WWII, the tax rate on the wealthiest was very high — over 90%. The government was creating massive deficits, nobody was saving, and the velocity of capital was very high. Simply put, the Great Depression ended when the government began was spending money it didn’t have to win a war, to build the industrial base that would equip the military — a classic example of Keynesian stimulus… and that’s how Keynesian stimulation ended the Great Depression. It wasn’t through tax cuts and small government; it was through deficit war spending and big government projects, paid for with high tax rates and industrial growth.

According to modern laissez faire theory, the 90% tax rate on the wealthy should have choked all the productive energy out of the economy, and the deficit spending should have created hyper inflation… but instead exactly the opposite happened. As a result, and again, contrary to all the free market myths, the high tax and high spending period known as the ‘Great Compression’ led to end of the Great Depression and the creation of the largest and richest middle class in history. Today, a report just out from the IRS and published by the Citizens for Tax Justice shows that the 400 highest earning Americans averaged an effective tax rate of 17.2% on gross income of $105 billion! If the ‘low tax rates stimulate the economy’ myth were true, then instead of the financial and economic crash we are currently in the middle of, we should be enjoying one of the greatest booms in history… but we’re not. Indeed, the historical record shows that as a general rule in the American economy, tax cuts create recessions and depressions, while tax increases create balanced budgets and steady growth.

The Rich Recapture the Steering Wheel

So where did this myth come from? In the late 1970’s, more than 30 years after the end of WWII, the wealthy recaptured control of the levers of policy and power that they lost in 1932, created and then pushed a ‘free market’ mythology through then President Reagan that lowering tax rates for the rich would stimulate the economy… a shibbolethic self-serving policy that is demonstrable fantasy. It was done for one reason and one reason only, a reason very different from their public and professed goals, and that was simply to drastically lower their own tax rate!

None of the ‘it’s good national economics’ slogans fabricated by their Madison Avenue marketing guys, like ‘greed is good’, ‘protect and reward those who innovate and risk’, ‘government is the problem, not the solution’, ‘small government is good government’, etc… none of them are legitimate economic arguments and have no goal other than to confuse, distract, and ultimately defeat the needs of the majority of middle and lower income people who would otherwise vote to raise taxes on the wealthy. In the end, for an educated society to have believed the idea that cutting taxes on the rich was ‘stimulative’ fiscal policy would be laughable… if they hadn’t been so successful in pedaling the snake oil that if played a major role in bringing a great country to its economic knees. Once again, as in Jonestown, it’s shown that drinking Kool-Aid can be dangerous to a society’s health.

Going forward, the Obama administration must confront this myth head on: it should identify it, describe it and defeat it, and return the nation to a more progressive national tax system. They must realize, and this current “Tea Party” madness is proof, that as long as the ‘tax cuts are stimulative’ myth goes unchallenged and undefeated, it can continue to claim legitimacy. It must be remembered that as of 2009, there is more than one full generation of Americans who are shocked to discover that as recently as 1960 the tax rates on the wealthiest Americans topped 90%… and it is this ignorance that the wealthy are counting on to hold on to their money.

Myth #2: Import duties and tariffs inhibit trade and shrink the economy, and the absence of duties and tariffs increase trade and grow the economy.

The widespread acceptance in this second ‘free market’ myth is even more unbelievable than the belief in the ‘low taxes are stimulative’ myth. As the economic history of the Great Depression shows the fallacy of the low taxation equals prosperity theory, world history shows us that every single major economic power, without exception, went through a period of high tariffs and industrial growth that lead to and created their wealth and economic power, how is it possible that tariffs do harm through restricting trade and growth?

The only way anyone could possibly believe that the general elimination of tariffs would lead to economic well-being and economic power would be if they also believed that the laws of economic development had been recently revoked and a new model for prosperity had arrived that didn’t use protective barriers in order to create a national industrial base. Unfortunately, every time that happens, when historical laws are believed to be revoked… the results are uniformly bad. Just as we recently discovered that the law of supply and demand hadn’t been revoked when the housing bubble burst, we are also discovering that a nation that does not protect its manufacturing base is one that cannot long maintain its economic power and the wellbeing of its people.

The History: Tariffs and Strong Nations

Were it so obvious that tariffs actually inhibited growth and hindered prosperity, then clearly no national policymaker would ever use them. That, of course, has not and never will happen, because it’s clear that eliminating tariffs will in fact do harm to the particular sector of the economy that asked for them and that they protect. It has been universally concluded by national policymakers, particularly since the 17th century, that it is better for a country to sell than to buy, to manufacture than to market, to create rather than copy. Indeed, why would any businessman ask their national leaders to tax particular imports if domestic interests weren’t going to be harmed by the unrestrained imports of a particular product?

If the above is true, then one must ask why is this argument advanced? In whose interest is it that nation-states are pushed to adopt trade policies that reduce or eliminate tariffs on all types of goods? History shows us that tariffs are an essential tool to be used in defense of national interests, so if it is not in their interests to reduce tariffs, in whose interests is it? Logically, it can only be a stateless group… and the only stateless group large, powerful and influential enough to distort international trade are the multinational corporations. The argument advanced that free-trade helps all countries is a fantasy that has been disproven time and again… but because it makes so much money for the corporations, they spend huge sums building, supporting and selling an economic theory that benefits principally themselves… and unfortunately, many national policymakers are taken in by their arguments to the clear detriment of their peoples interests.

The money they spend supports countless ‘think tanks’ that pump out… shall we call them ‘rationally challenged’ economic theories day in and day out. They write papers that support and defend their right to move capital and manufacturing facilities at will between countries in the name of low prices and market efficiency… all while they stockpile their earnings in tax havens protected by the very nations they pillage. All in all, as I said at the start of this section, it’s more amazing that people accept the ‘free trade no tariffs’ theory than it is that they believe the ‘don’t tax the rich’ theory.

Like the example of the frog who won’t jump out of water that is slowly heated, eventually perishing in the boiling liquid because the change is so gradual, major corporations have slowly changed from being national to international entities while the nations where they were originally headquartered still think of them as national businesses and believe that they act in the national interest. Alan Greenspan testified before congress that he was shocked to discover that bankers did not act in the best interest of their banks. He would, I assume, be equally shocked to discover that multinational corporations no longer act in national interests, but in their own best interests… and therein lies the ‘flaw’ in the entire free-trade argument:

Why this fact is not manifestly obvious to everyone is a mystery, but neither should it have come as a surprise to Mr. Greenspan that individuals would not act in the best interest of their companies but rather in their own best interests …

How to Stay Prosperous in a Flat World

Recognizing that nations can only become prosperous industrialized nations by protecting their industries through tariffs as they mature, however, is just the first part of a ‘new’ economic understanding that must come to dominate national policy decisions. The second part of this truth is best arrived at by finding the answers to the following questions: how can a high labor cost nation compete with a low labor cost nation in any labor intensive economic endeavor that has no inherent geographic restrictions that limit the movement of the activity? More to the point, do they even want to try and compete, or should they simply let the low labor cost nations take over global ‘menial labor’ manufacturing business and dedicate themselves to ‘high tech’ and ‘high paid’ jobs? The answer to the first question is, simply, they can’t compete without some adjustments, while the answer to the second is that they must. In today’s flat world, there is no such thing as a secure manufacturing job, high tech or otherwise, so long as labor cost is the principal component of production costs. Therefore, if they can’t compete on an ‘even’ footing with low labor cost nations, but they must if they are to retain their industrial base, what can be done?

Slay the Myths

The first thing that must be done is to slay the myths that got us to this juncture. Furthermore, the discussion must be stripped of all the nationalistic jingoism that the argument is usually presented in – like ‘The American worker is the greatest worker in the world, and ‘We can out compete any workforce on the planet!!’ – and all the other countless and silly slogans manufactured by the corporate spokespeople intended to paralyze all rational thought behind false pride wrapped in the national flag… statements like ‘It’s good policy to ship overseas all the menial labor jobs and hold on to the high technology, high paying jobs.’ If national economic policy continues to be made in the boardrooms of the large multinational trading and manufacturing corporations, no one should be surprised when it favors them and not the nations where they are headquartered. Furthermore, as long as efficiency is the dominant component that drives all subsequent decision making, everything else runs the risk of being sacrificed at it’s altar; jobs, unions, political stability, governance, development policy, tax policy, import policy… everything falls to the ax of efficiency.

In business… business is business, not whim or wannabe. Facts are facts, costs are costs, advantage is profitable and disadvantage is bankruptcy. Therefore, if in our increasingly flat world nearly all else is equal, labor costs become the dominant factor in the location of production facilities. In a world where businesses routinely compete for a tiny or marginal price advantage, where a marginal rise or fall in the value of a national currency can mean the difference between success or failure, labor cost differences on the order of 50:1 are not merely ‘helpful’, they are definitive, and any business that does not take advantage of them is no longer in business tomorrow.

Thus, the board-room designed solution to the ‘high wages are ruining the bottom line problem’ is simply to move to where articles can be most ‘efficiently’ produced and raising a rear-guard trading myth to insure that the rich countries don’t raise tariffs that would inhibit sales. This abandonment of national policy to corporate boardrooms can only have one outcome… the lowering of the standards of living and generalized deflation in the historically developed countries. Without manufacturing, they will not be able to produce enough ‘value added’ products nor create the well-paid jobs that between them create the growth essential for economic success. In this fashion, the companies, wittingly or not, become the hammers used to drive the trade nails home into the coffins of the rich nations.

National Solutions are Good Solutions

What can be done? First, and in general terms, each country must start to take a clear-eyed look at their particular national situation and make decisions based upon national interests. They can no longer allow corporate boardrooms to pedal economic myths that obfuscate the fact that national policies must reflect, resolve and protect national interests. For example, U.S. leaders must recognize that what is good for GM, IBM, Nike, HP and Fruit of the Loom is not necessarily good for the people of the United States … just as what is good for Volkswagen and Siemens is not necessarily good for the people of Germany. Further, the national entities must not make decisions based upon one size fits all economic theories cooked up for the benefit of private capital and worshiping at the god of efficiency. Theories of trade and development that do not bring prosperity, stability and wellbeing to any nation need to be discarded in favor of pragmatic solutions that do.

Small is Beautiful … and Stable

Second, all nations should be encouraged, each within their possibilities, to create their own industrial bases, however inefficient or small, and protect and grow them. It is ALWAYS better to have an industrial base, even an inefficient one, than none at all. In the absence of a domestic national ability to industrialize either broadly or in specific areas, nations should at a minimum require multinationals to produce in the country if they intend to sell there, as Mexico has done for many years with the automotive industry. If that means that the products will be more expensive for national consumers, so be it. It is far better to have an industrial base and the jobs that they create than to have the same products that are consumed domestically produced more cheaply in another country.

The model that we have used to date, that of manufacturing where it’s cheapest and exporting all over the world from those plants has failed. Among its many problems, this model ends up with manufacturing, trading and financial businesses on a scale that threaten national political independence, that are concentrated regionally instead of diversified globally, and instead of smaller, possibly less ‘efficient’ but much more stable entities that can weather the normal ups and downs of the business cycle, large multinational enterprises that become ‘too big to fail.’

The ability of businesses and industries to persevere in adversity is critical, and is far easier when the design is many small bases as opposed to a few gigantic bases. When national economies are more balanced, not dependent upon either massive exports or crippling imports to resolve their capital or consumption needs, they are more stable both in good and bad times. Furthermore, the jobs and the ‘value added’ portion of the industrialized part of their economies will tend to stabilize and equalize incomes, strengthen local organized labor, grow and mature the industries within each economy, and increase social and political governability.

Of course, a policy shift of this nature would be fought tooth and nail by all the major industrial and trading multinationals, from Toyota and GM to Sony and Nokia. It would immediately be pointed out, and correctly, that consumers would almost universally pay more for the products they consume.

However, the argument that cheaper products equals a better economy was proven wrong once and for all in the American consumer and then global financial meltdown of 2008: there is no there there.

What good, after all, are cheap products if there are no jobs? Price will always be a major factor in consumption, but that doesn’t mean that it should be the determinant factor in the formation and execution of new national industrial and economic policies that put jobs, the environment, and political and economic stability behind price.

Destroying the myths of laissez faire capitalism is critical to forging a new model, one that will rebuild and protect not only the American economy, but all economies struggling to recover from the crash of 2008 and the abuses of the Washington Consensus and Friedmanite Capitalism. And if, after surveying the damage done by them over the past thirty years the reader still thinks that low taxes create wealth and that free trade produces prosperity, I would simply ask;

“Who are you going to believe … me, or your lying eyes”

Our enormous trade deficit is rightly of growing concern to Americans. Since leading the global drive toward trade liberalization by signing the Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1947, America has been transformed from the wealthiest nation on earth – its preeminent industrial power – into a skid row bum, literally begging the rest of the world for cash to keep us afloat. It’s a disgusting spectacle. Our cumulative trade deficit since 1976, financed by a sell-off of American assets, exceeds $9.2 trillion. What will happen when those assets are depleted? Today’s recession is the answer.

Why? The American work force is the most productive on earth. Our product quality, though it may have fallen short at one time, is now on a par with the Japanese. Our workers have labored tirelessly to improve our competitiveness. Yet our deficit continues to grow. Our median wages and net worth have declined for decades. Our debt has soared.

Clearly, there is something amiss with “free trade.” The concept of free trade is rooted in Ricardo’s principle of comparative advantage. In 1817 Ricardo hypothesized that every nation benefits when it trades what it makes best for products made best by other nations. On the surface, it seems to make sense. But is it possible that this theory is flawed in some way? Is there something that Ricardo didn’t consider?

At this point, I should introduce myself. I am author of a book titled “Five Short Blasts: A New Economic Theory Exposes The Fatal Flaw in Globalization and Its Consequences for America.” My theory is that, as population density rises beyond some optimum level, per capita consumption begins to decline. This occurs because, as people are forced to crowd together and conserve space, it becomes ever more impractical to own many products. Falling per capita consumption, in the face of rising productivity (per capita output, which always rises), inevitably yields rising unemployment and poverty.

This theory has huge ramifications for U.S. policy toward population management (especially immigration policy) and trade. The implications for population policy may be obvious, but why trade? It’s because these effects of an excessive population density – rising unemployment and poverty – are actually imported when we attempt to engage in free trade in manufactured goods with a nation that is much more densely populated. Our economies combine. The work of manufacturing is spread evenly across the combined labor force. But, while the more densely populated nation gets free access to a healthy market, all we get in return is access to a market emaciated by over-crowding and low per capita consumption. The result is an automatic, irreversible trade deficit and loss of jobs, tantamount to economic suicide.

One need look no further than the U.S.’s trade data for proof of this effect. Using 2006 data, an in-depth analysis reveals that, of our top twenty per capita trade deficits in manufactured goods (the trade deficit divided by the population of the country in question), eighteen are with nations much more densely populated than our own. Even more revealing, if the nations of the world are divided equally around the median population density, the U.S. had a trade surplus in manufactured goods of $17 billion with the half of nations below the median population density. With the half above the median, we had a $480 billion deficit!

Our trade deficit with China is getting all of the attention these days. But, when expressed in per capita terms, our deficit with China in manufactured goods is rather unremarkable – nineteenth on the list. Our per capita deficit with other nations such as Japan, Germany, Mexico, Korea and others (all much more densely populated than the U.S.) is worse. My point is not that our deficit with China isn’t a problem, but rather that it’s exactly what we should have expected when we suddenly applied a trade policy that was a proven failure around the world to a country with one fifth of the world’s population.

Ricardo’s principle of comparative advantage is overly simplistic and flawed because it does not take into consideration this population density effect and what happens when two nations grossly disparate in population density attempt to trade freely in manufactured goods. While free trade in natural resources and free trade in manufactured goods between nations of roughly equal population density is indeed beneficial, just as Ricardo predicts, it’s a sure-fire loser when attempting to trade freely in manufactured goods with a nation with an excessive population density.

If you‘re interested in learning more about this important new economic theory, then I invite you to visit either of my web sites at OpenWindowPublishingCo.com or PeteMurphy.wordpress.com where you can read the preface, join in the blog discussion and, of course, buy the book if you like. (It’s also available at Amazon.com.)

Please forgive me for the somewhat spammish nature of the previous paragraph, but I don’t know how else to inject this new theory into the debate about trade without drawing attention to the book that explains the theory.

Pete Murphy

Author, “Five Short Blasts”