The myth about jobs and taxes,

and why Obama took the deal

By Sid Eschenbach / The Rag Blog / December 14, 2010

With little time left in this Congressional session, legislative scheduling should be focused on these critical priorities. While there are other items that might ultimately be worthy of the Senate’s attention, we cannot agree to prioritize any matters above the critical issues of funding the government and preventing a job-killing tax hike.

With this passage in the letter sent to Majority Leader Reid from the entire Republican caucus, the Republicans again assert one of the central myths of Chicago school economics — that raising taxes kills jobs. It is repeated endlessly, this lie, this wholesale fabrication. This straw man specifically constructed in order to give greed a veneer of respectability (not to say virtue) is at the heart of modern economic myth — and is at the heart of current American national economic failure.

It is the industrial sized fig-leaf used to confuse and convince the ignorant while it protects both the money and the power of the wealthy, and until this lie is disproven and the liars that advance it unmasked, there can be no hope of holding a fact-based national conversation regarding the proper funding of the government.

Indeed, given the ease with which it can be disproven both empirically and theoretically, it makes one wonder about the real agenda of the Democratic Party, a party that has since the time of FDR understood that a system of strong progressive taxation is in the best economic interests of the nation. But Democrats have thus far chosen not to contest the neoliberal framing.

Could it be that there is, under certain circumstances, a reason that cutting taxes is indeed stimulative and thus in the best interests of the Obama administration?

Historical Proof that high taxes don’t kill jobs

Empirically, the evidence is clear: there is not now nor has there ever been — since personal income taxes were instituted in 1913 — any real statistical relationship between low tax rates and job-creating prosperity — or the alleged and corollary relationship between high tax rates and unemployment.

A statistical analysis of the data (historical tax rates vs. historical unemployment rates) shows that, to the degree a statistically valid (p<.05 relationship exists at all employment and general prosperity are more directly related to higher taxation but the conditions aren linked statistically. past years have shown that unemployment can be high under both low tax regimes just as it regimes. therefore there is either no between rates or so weak easily overcome by other stronger economic factors. whatever case fact remains empirical historical proof this over nearly a century of taxes kill jobs. while many specific examples could following example simple short clear. world war i was watershed in history american income were raised significantly order pay for huge additional expenditures. before advent another neoliberal fantasy cutting>increases government revenue.

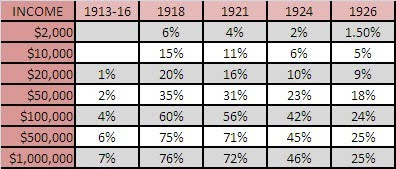

Therefore, as shown in the chart below, in 1917 the top marginal rates were raised from 7% to 67%, and they stayed high through 1921 to allow the government to get rid of the budget obligations created during the war. As a result of these rate increases, the share of revenue gained from income tax continued to rise after the war, reaching a peak of 69 percent in 1920.

By 1920, with the debt generally paid, the consensus of government was that tax rates could and should be cut, especially from the upper brackets. The results were the income tax cuts in 1921, as well as following cuts again in 1924 and 1926 due to a continued growth in government surpluses. Rates changed during this period according to the following table:

Reviewing the data, we see that in 1918 rates were raised to pay for the war, which indeed generated the greater revenue sought. After the debts were paid off, marginal rates were again lowered in 1924, and as a result, government revenues from income tax diminished. The most salient point of this data, however, is that from start to finish, with rates changing from 7% to 76% and back to 25% (the largest rate changes in the history of U.S. taxation), the national unemployment rate never varied more than 3%.

And we all know what happened next: from the 25% top tax rate of 1926, Income tax rates remained low right into the Great Depression and the highest unemployment rates the country has ever seen — something that would be technically impossible if low tax rates did in fact create jobs.

To be sure, our century of taxation repeats this theoretically impossible feat time and again, most recently from 2003-2008. However, as Goebbels proved, a lie repeated often enough can defeat even reality, and “high taxes kill jobs” is no exception. In the famous words of the unfaithful husband trying to reassure his angry wife: “Honey, who are you going to believe: me, or your lying eyes?”

In its latest iteration, it’s sold to a gullible and vain public with variations on the theme of: “You can spend your money more wisely than the Government” — which is itself just another emotional link to the underlying and insulting Republican trope of inept government: the oft used “Hello, I’m from the government and I’m here to help!” joke. Moreover, while this general argument that private spending is somehow more “efficient” than government spending has never been true, it is especially not true in today’s import dominated economy.

What is ‘economic stimulus’ anyway?

In traditional capitalist theory, when economists speak of “stimulating” an economy (usually with the goal of lowering unemployment), what they are trying to do in “econo-speak” is to “increase aggregate demand,” and this is done by adding money to the system. Theory and reality are at this point in agreement, because people do indeed always spend more when they have more. So the idea behind ‘stimulation’ is simple: to somehow get more money into society’s pockets, its hands, its stores, banks and businesses.

There are really only two generic ways to “increase aggregate demand”: either economically, by somehow “juicing the pot,” or entrepreneurially, through creating a new demand that drives new and greater spending. An example of the second is the creation of the IT industry and the 22 million jobs it spun off during the Clinton administration.

Unfortunately, as a policy tool it’s beyond the reach of economics, as no economist has as yet figured out a way to create, at will, transformative technologic revolutions and the growth that comes with them. For practicing economists and government functionaries, therefore, the tools available are the traditional — economic fiscal and monetary policy — and the use of either of these does indeed have an impact on growth and jobs.

Monetary and fiscal stimulation

Economists use the formula “GDP = CS + BI + GS + BT” to calculate the size of national economies and measure their movement. The total, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is considered to be equal to the sum of consumer spending (CS), business investment (BI), government spending (GS) and net balance of international trade (BT). In order, then, to stimulate the economy, one or more of these must increase, thus creating a larger total sum of the parts.

As noted above, economists can do this in one of two ways: using monetary or fiscal policy. What most people don’t understand, however, is that both are tools of debt. The ignorance of this fact even among those who should know better was shown most recently in the last electoral cycle, when an ad for a tea party candidate had her listeners in hysterics when she pointed out that the Democrats advocate spending their way out of the recession! Very funny!

However, as Greece and other nations have proven, austerity in recession only further kills growth, so there is no there there. Contrary to common sense, the time for austerity is not when in recession, but when in surplus. Recessions stipulate spending, while prosperity calls for balanced budgets.

Debt as stimulus

Using the tool of private debt as stimulus – monetary policy — the central bank lowers interest rates in order to stimulate the economy. This is because lower rates generally lead to increased bank lending, and lending is the most direct and usually fastest way to create and circulate the new money needed to stimulate growth, increase the GDP and exit the recession.

Lower interest rates generally increase both consumer spending (CS) and business investment (BI), because both sectors tend to borrow more money at lower rates. When CS and BI go up, the total GDP goes up — which is the essence of stimulus. In terms of the Great Recession, the Fed has, of course, ridden this horse until it can run no more, having reduced interest rates to near 0% some time ago.

Fiscal policy, on the other hand, refers to increasing GDP via either a) increased government (deficit) spending (GS), or b) lowering tax rates. The a) part of the fiscal stimulus theory, that deficit spending by the government is stimulative, is straightforward. When one calculates the GDP, it doesn’t matter if the amount of government spending is paid for… or not. Therefore, when the government spending (GS) is increased, it directly increases the total amount of capital in circulation, thereby increasing “aggregate demand” — or GDP — which, again, is the goal of the exercise.

In the Great Recession, along with reducing the federally controlled base interest rate to nearly 0% (monetary policy), fiscal policy was both the vehicle of choice and necessity for the Obama administration, and it did so primarily by borrowing and then spending the famous $700 billion dollar stimulus package of deficit spending.

It had to do this to try to stem a massive deflationary spiral created by the bursting of the global real estate bubble. It was an effort to support GDP through government spending in the absence of consumer or business spending — and thus avoid the very real possibility of a second Great Depression.

In summary, both monetary and fiscal policies are about one thing: increasing total capital by increasing debt. Monetary policy encourages both consumer (CS goes up) and business (BI goes up) debt, while fiscal policy refers to an increase in government debt (GS goes up).

What about b), the ‘cutting taxes is fiscal stimulus’ part of fiscal theory?

The argument made by neoliberal economists is this: that cutting taxes increases the amount of disposable income in the hands of consumers, and thus increases spending and demand in the consumer sector — which is certainly true. However, both history and math shows us that cutting taxes by itself creates no new money, as the amount “given” to consumers (increase CS) through a tax cut is the same amount ”taken” from the government (decrease GS).

Therefore, a tax cut cannot possibly create an increase in total aggregate demand any more than a tax hike decreases it. What goes up in one column is what goes down in another: the classic “Robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Furthermore, the argument that any increase in consumer demand increases business hiring to meet that demand is equally true for government spending, whether the government spends it or it’s spent by the wage earners themselves, it’s the same money with essentially the same net results.

Why the Obama administration agreed to an extension of the Bush tax cuts

As noted above, however, there is a way that cutting taxes can be stimulative, but only under one particularly cynical outcome: the case wherein there is no commensurate cut in government spending that would offset the cut in taxes. In that event, by simple mathematics there is a net growth of money in circulation, because, if revenue is reduced while spending is not, there will be an unavoidable increase in deficit spending in order to make up for the tax revenue lost — and we’re right back to good old fashioned fiscal stimulus. And that, we know, grows the economy perforce.

Therefore, the interests of both the nation and the Obama administration are being met by the politically contra-indicated policy of extending the Bush tax cuts, and that is why the Obama administration, after doing the math, agreed to the deal. As they are not and will not be paid for, it requires the government to borrow the new money to pay for them and thus stimulate the economy — something the Republicans would never allow the Democrats to do any other way,, because it is not in their political interests that Obama get the country out of the recession.

It’s not coincidental that the Republicans under Democratic administrations fight for “balanced budgets,” while ignoring them during their own party’s rule: they too have done the math and know that fiscal stimulus works. Fortunately, on the issue of tax cuts, they drank a bit too much of their own Kool-Aid and forgot the real reason behind the reason given publicly that tax cuts are stimulative — and by this “win” are forcing the Democrats to do what they won’t allow them to do any other way: to fiscally stimulate the economy.

This is something that is most definitely not in their political interests, as the last thing they want is for Obama to be a success. However, sometimes lies take on uncontrollable lives of their own, and the lie that cutting taxes is stimulative — because, “Everybody knows that you don’t raise taxes in a recession” and because “Consumers spend their money more wisely than the government” and “Raising taxes kills jobs” — has just given the Obama administration a new $200-$700 billion dollar economic stimulus package. And contrary to common sense and absent new trade or industrial policy, spending is in fact the only way out of this or any recession.

It would have been far preferable, both economically and politically, to end the tax cuts and also pass another large stimulus of the same amount based around infrastructure spending, but it’s a simple fact that given the realities of the modern Tea-publican party, that was not to be. Therefore, the bottom line is this: while this may be terrible politics both for Obama as a person and for the Democratic party as a whole, absent structural reforms of trade and industrial policy, it is tragically and paradoxically the best anti-recession economics that the country can hope for.

[Sidney Eschenbach, 62, lives and works in Guatemala. His thoughts regarding developmental economics and trade are based on decades of development work in Latin America at various levels, community, corporate and national.]

Impressive heavy lifting, Sid. Thanks!