It was a conscious effort initialized and orchestrated by corporate interests.

It is no secret that throughout American history the labor movement has been infiltrated by government and corporations. This private spying business had its roots with the Pinkerton private detective agency, which after the Civil War earned the reputation as a paid strike breaker and union buster.

The Pinkerton business model soon led to a proliferation of private detective agencies dedicated to the same goal of destruction of the organized labor movement. American industrialists employed them in the quest for profit and at the expense of its workforce as the struggle between labor and capital intensified into sometimes bloody conflicts. And it should be noted that the information provided by those agencies and agents many times proved to be full of misinformation.

The conflicts between labor and capital continued to build to a head in the early years of the 20th century. Working and living conditions were getting worse, the American farmer was being reduced to farm tenancy, American capitalists absorbed more capital and entrenched themselves into an economic dictatorship, the militant Industrial Workers of the World organized and responded with energetic unionization efforts, a growing socialist political movement emerged to challenge this economic hierarchy, the United States was entering the global arena as a major political and economic player, and the rumblings of war started in Europe.

And so our story begins.

And so our story begins.

In San Antonio in early May 1917, Special Agent in Charge Robert L. Barnes of the Bureau of Investigation (the predecessor of today’s FBI), received a communication from James McCane of the McCane Detective Agency in Houston. The letter, dated April 19 from the McCane’s Agency’s “Operative 100,” was presumably important enough for McCane to forward to the B of I several weeks after its initial writing.[1]

Operative 100’s “Special Report” from Canton, Texas, talked of how he had attended a meeting of an organization called the “Farmers and Laborers Protective Association of America on Saturday night 17th inst., instead of Thursday Night 15th inst.”[2]

His report begins with a verbatim transcript of the constitution and bylaws of the FLPA, and then reports that “the Constitution seems very conservative, but the inside working of the order is extremely radical. They claim to have organized in five states and the latest report shows 120,000 members.”[3]

Operative 100 continues by describing some of the Masonic-like rituals of the organization and depicts a cooperative buying policy to by-pass local merchants. He describes them as “against militarism and obligates them not to go to war,” and to stand as a “compact body” and “fight not for the mast[er] class but to fight the battles of the working class.”[4]

He concludes his report with “the I.W.W’s or the B.T. of Ws [Brotherhood of Timber Workers] are not in it.”[5]

By most accounts the FLPA was first formed in Leuders, Texas, in November, 1915, most probably as an offshoot of the Oklahoma-based Grower’s Association,[6] but also with influences from the Texas Farmer’s Union, the Texas Land League, and other smaller farmers’ cooperative associations. Politically it was primarily composed of impoverished tenant farmers who probably voted socialist, as it appears its local chapters were primarily in areas of relatively vocal socialist organization.

Whether Operative 100 fabricated his claim of 120,000 FLPA members or whether he was misinformed is unclear; at the time of its persecution the FLPA membership most certainly never exceeded 10,000 members.[7] Even while FLPA organizer George T. Bryant exaggerated membership figures to the tune of 50,000 at the November 2016 convention of the Texas Socialist Party, in February 2017, the organization only had 2,300 paid members.[8]

Operative 100’s statement that there were no members of the Industrial Workers of the World in the FLPA was also in error, as it has been documented that there were several, including FLPA organizer Bryant, Will Bergfeldt, Guy Cooper, and R.W. Mills.

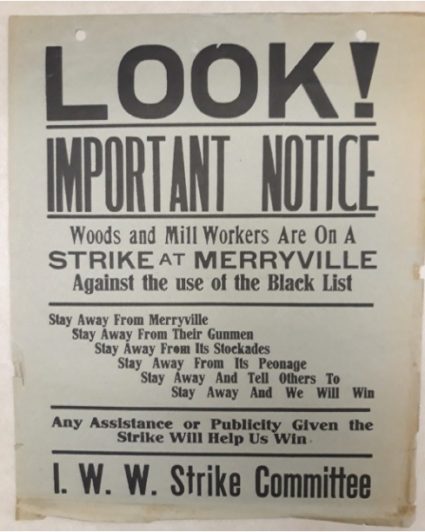

Most telling is Operative 100’s statement that there were “no B.T. of Ws” in the FLPA organization. The Brotherhood of Timber Workers in Louisiana and East Texas had pretty much dissolved by the spring of 1913 following the Grabow Massacre, the failure of the Merryville Strike, and retirement of BTW President Arthur Emerson for reasons of ill health. Why would Operative 100 have specifically mentioned this in his initial report, over four years after the demise of the BTW?

There can only be one logical answer to this question. As an employee of the McCane Detective Agency, Operative 100 was probably instructed by his employer to determine if there were any signs of resurgence of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers within the FLPA and he was reporting back on that specific enquiry. The McCane Detective Agency itself, as a private business, was more than likely retained by a corporate sponsor to determine any FLPA connections with the BTW. The corporate industrialist most logically to have specifically feared the Brotherhood of Timber Workers and the IWW would have been the Kirby Lumber Company.

The Kirby Lumber Company was

vehemently anti-union.

The Kirby Lumber Company was vehemently anti-union, and certainly made extensive use of private detective agencies to surveille the activities of the BTW, employing the services of the McCane Detective Agency and the Burns Detective Agency, as documented within the pages of its corporate archives.[9] When the Kirby Company organized the Southern Lumber Operators Association in 1907, the expressed mission statement of the Association was to “resist any encroachment of organized labor.”[10]

Operative 100 followed up his report of April 19 with an additional report he started on April 21 and completed on April 28:

Today, I received information through reliable sources, of above organization, that at the last state convention, there was in the delegation, Miners, Railroad Trainmen, Factory workers, Lumberjacks, and Farmers. All pledged for the protection and common good of each craft.

I have also learned that in case of labor troubles, they plan to destroy banks, and other large business institutions, which exploit the working class.

Also that plans are laid and being laid to dynamite banks and other institutions….[11]

Objectively, Operative 100’s second report is dubious for a number of reasons, not the least being the reference to the unnamed “reliable sources” which tend to cloud any professional investigation. Additionally, the FLPA state Convention referenced in his report actually transpired in early February 1917, a couple of months prior to 100’s report.[12] (It should be noted here that the February convention declined to affiliate with the Industrial Workers of the World and passed a strongly worded anti-war resolution wherein it was declared they would “refuse to shoot our fellow man.”[13]) The sudden mention of an organizational plot to dynamite banks and business institutions is also highly suspect, but would work within the operative’s testimony of corroborating with other spectacular labor cases of the time, including the Mooney case in California.[14] In the same report, Operative 100 declares that Tom Mooney is a member of the FLPA{15}, an outright fabrication.

A much calmer third report filed by Operative on April 24th reports that women were now admitted into the FLPA and that communications were to be undertaken by secret telegraph. He also reports that he was not elected to the upcoming FLPA Convention in Cisco on May 5, having been defeated by four votes.[16] The admission of women had actually occurred at the February convention.[17]

Apparently Special Agent Barnes in San Antonio had some questions about Operative 100’s reports; Agent W. W. Green in Houston is instructed to contact the McCane Detective Agency to determine the identity of Operative 100. Green is met with an outright refusal:

McCane declined to disclose the name of the operative or to approve any plan to have such operative report direct to Mr. Barnes or any other representative of the Department of Justice for the following reasons:

1) That if the operative should be compelled to come from under cover it might become necessary to give up his employment or leave this part of the country or to forfeit his life, as he believed that the organization named was a dangerous body of men; and

2) That the McCane Detective Agency is a private organization operated for profit, and that operative 100 is a paid employee of that agency. He stated that any further information furnished or investigation made would have to be a result of arrangements to be made with the agency as an organization or with Mr. McCane personally. For such service a fee would be charged of $8 per day and expenses, and no time limit would be set on the time necessary to secure results from the investigation.[18]

Agent Green expressed his skepticism to Barnes:

It seems to agent that this investigation could be made more economically through the services of an operative to be sent out from San Antonio to report directly to Mr. Barnes, than through the use of the McCane agency, and with as good results. It should not be difficult for such operative to get in touch with this association, if in fact it really exists; and such an arrangement would eliminate any possible profit to the McCane agency in case it should develop that this report is without real foundation of fact and merely devised for the purpose of securing a profitable job from the Government.[19]

The May 5 Convention of the FLPA was held as planned at Cisco. Paramount on all the delegates’ minds was the current war fever which was spreading through the nation at the time. The socialist movement in Texas, of which the FLPA was peripherally a part, was adamantly against any sort of United States involvement in the overseas war. The United States had entered the war on April 6, but there was strong sentiment against U.S. involvement, and sentiment was especially vocal against the idea of a national conscription to fight the war. Delegates were instructed by FLPA Secretary Samuel J. Powell to decide “on what effort you want to take in our effort to defeat conscription.”[20]

A “majority report” was introduced at the convention to urge the FLPA to take up arms and forcibly resist the draft, but the convention ultimately voted for a “minority report” which called for a conference with other labor organizations and to refuse to sell crops to war speculators.[21]

While there were no doubt hotheads in the FLPA who preached a militant opposition to the upcoming Selective Service Law, it must be emphasized that the FLPA as an organization did not advocate violence against the United States government nor corporate business.

Special Agent Barnes had taken Operative 100’s inflammatory reports seriously.

Meanwhile, Special Agent Barnes had taken Operative 100’s inflammatory reports seriously enough to begin a B of I investigation into the purported allegations concerning the FLPA; he forwarded that information to the U. S. Attorney’s office in Fort Worth. On May 8, Agent B. C. Baldwin reported that there was no charter or permit for the FLPA at the Texas Secretary of State’s Office, and that the Secretary of State had no record of the organization.[22]

Also on May 7, the new U. S. Attorney for the Northern District of Texas, Wilmot C. Odell, immediately answered Barnes, calling for an immediate investigation into the FLPA with the intent of obtaining grand jury indictments the following week, and to obtain the needed witnesses for those indictments.[23]

Odell’s enthusiasm for prosecution was more than likely encouraged by a letter forwarded to his office on May 5th by Special Agent Barnes via Agent Will Green from the Postmaster of Cisco, R. A. St. John:

There are secret societies meeting all over this section of the country. They held a closed door convention here today. I am told that most of them are socialists. They are creating a systematic way opposition to conscription.…I am sure that if this disloyalty is not checked that harm to our government will follow….Please answer promptly, I am anxious to do my whole duty.[24]

Odell’s case for prosecution was also presented in a letter on May 15 to U. S. Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory, which seemed to echo many of the allegations made in Operative 100’s report of April 21:

Concerning my letter May tenth regarding farmers and laborers protective association. Have absolute and conclusive evidence of well organized force throughout west Texas to forcibly resist conscription. State meeting held at Cisco, May fifth, with delegates from many Texas counties. Organization perfected. Officers selected. Killing of conscription officers, destruction factories, bridges, and other property, advocated with [ ] of violence against anyone disclosing purposes of organization. Members have been buying high power rifles and ammunition. Much uneasiness is aroused in communities where purposes organization are becoming known and some of informers think are in actual danger. Believe leaders should be indicted if possible with wide publicity, regardless of jurisdiction, this division, and re-indicted at Abilene if necessary. In view of importance and urgency would like to have your views as to best course to pursue.[25]

The investigations against the FLPA began in earnest with the Bureau of Investigation now doing most of the leg work. A directive had been issued by the Assistant Postmaster General in Washington instructing local postmasters to surveille the mails to obtain more evidence on the FLPA[26], the names of FLPA members were collected, and their interrogations began.

Odell was concerned about finding the correct charges for which to indict the members of the FLPA. There was some discussion on whether the Neutrality Act could be used, or whether existing conspiracy laws could be applied. Unlawful assembly was another possible charge. After all, it would be difficult to prosecute for talking out against conscription if there were not a conscription law on the books. This issue was solved by the passage of the long-awaited Selective Service Act on May 18, 1917.

It should be noted that the Selective Service Act did not set out any criminal penalties for speaking out against the draft or organizing against the draft. The only criminal penalties mentioned in the act were for non-registration, punishable by a misdemeanor charge of one year imprisonment.[27] It would be for the Espionage Act, passed by Congress on June 5, to criminalize anti-war dissent and opposition to the draft.

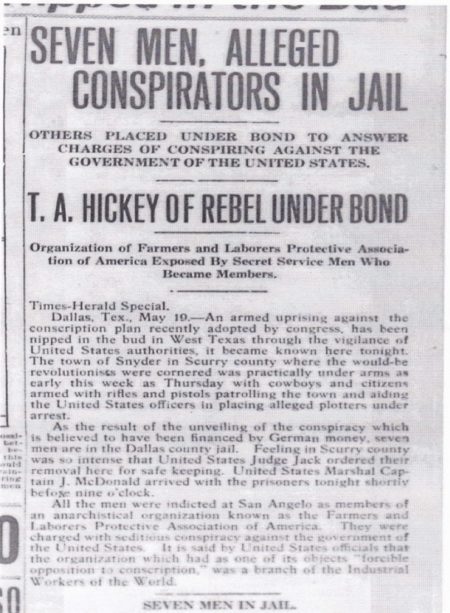

On May 19, the day after the enactment of the Selective Service Act, Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Texas, William E. Allen, announced the discovery of a massive conspiracy to resist the draft on the part of the FLPA.[28]

The “wide publicity” that Odell had mentioned in his letter to U.S. Attorney General Gregory had gone into effect.[29] The newspaper coverage extended nationwide. The New York Times reported that “The anarchists, the I.W.W. people, the always hustling, noisy advocates of disorder…are doing their best to encourage and organize resistance to conscription….The hour of patience is past. The hour of punishment, swift, implacable, just, is come.”[30]

The purge of the Texas socialist movement had begun.

The first indictments from the federal grand jury in San Angelo came in the evening of May 18, just hours after the passage of the Selective Service Act. In the following days, hundreds of socialists, Wobblies, and FLPA members were arrested statewide, including Texas Socialist Party secretary William Thomas Webb, Socialist Legislative candidate J. L. Taff of Gilmer, FLPA organizer George L. Bryant, Wobblies R. L. Mills and Will Bergfeldt, and Socialist Party of Texas organizer Thomas A. Hickey, editor of the socialist newspaper The Rebel.

Operative 100 was modest in his role as promoter of the initial investigation: “What I meant in previous report about keeping my name secret was not to let it out to the public. Press reports has given a Jones County man the credit. That suits me O.K.” [31]Operative 100 also contributed to the FLPA round-up by providing the names of the members of his own and other FLPA locals, but stated that a lot of the rumors were “just idle talk started in a jocular way.”[32]

In his report of July 9, Operative 100 may have accidentally identified himself as the Secretary of FLPA Local #101 in Canton.[33] This post would have put him in a position to monitor FLPA correspondence, activities, and membership, and which would have justified his position as an undercover operative. In any event, by May 22, James McCane had released Operative 100’s identity to the Bureau of Investigation:

Mr. McCane came through this morning with the name and address of Operative 100, which has heretofore been refused. The name is G.E. Mabry, Canton, Texas. Mr. McCane states that this man has formerly been employed by the Wm. J Burns Detective Agency, but that this is the first time he has ever been employed by the McCane Agency. No money has been paid him so far in connection with this case. Mr. Mabry is a farmer and is very busy at the present with his crops.[34]

Operative 100 was then released by the McCane Agency to be hired by the Bureau of Investigation.[35]

McCane had stated that Operative 100 was a paid employee of the McCane agency.

McCane had previously stated that Operative 100 was a paid employee of the McCane agency, but inconsistently suggests in his remarks to Agent Green that no pay was given to Operative 100.

Giles Earl Mabry, Operative 100 of the McCane Detective Agency, was born March 12, 1889, in Stokes Township, Madison County, Ohio, the son of Earl V. Mabry and Mary Katherine “Massie” Cruise Mabry. He is living with his father and younger brother and sister in Burleson County, Texas, by 1910. His older brother, Liskie Terrence Mabry, was born in Virginia in August 1875.

In 1912 older brother Liskie was employed as a private detective with the William J. Burns Detective Agency and the McCane Detective Agency in Louisiana. He was retained in that role as an undercover operative for the Kirby Lumber Company/Southern Lumber Operators Association. In his capacity as that operative, he joined the Brotherhood of Timber Workers in 1911 and infiltrated the inner ranks of the BTW as a statewide organizer for the BTW[36] and provided regular reports to corporate management.[37]

One of Liskie Mabry’s exploits is particularly descriptive as it portrays how he and another operative, “Operative 6” (presumably one “Hutchinson”[38]), engineered the drunkenness of BTW organizer J. F. Cox into making statements in front of a prearranged company witness about dynamiting the lumber mills at Warren. “Why not blow up the whole saw mill?” Mabry is reported as prompting. “Mabry and I have all our plans laid out for this stunt coming off at Warren, Texas, and put them up to Manager J. H. Baber, who approved same,” Operative 6 reported.[39]

Liskie Mabry was called as the star prosecution witness for the trial of the 59 BTW unionists following the deadly gunfight at Grabow, Louisiana on July 7, 1912, which killed six people, admitting to his undercover role, but swearing he had never organized the Timber Workers with the intent of betraying them. He also testified that he did not know if his brother Giles was a detective or not.[40] Fellow Burns detective Tom Harrell also testified for the prosecution; Harrell had previously boasted about giving “a good beating” to I.W.W. Organizer E.F. Doree.[41]

Giles Mabry was more than likely also employed by the Burns Agency at that time, in spite of Liskie Mabry’s testimony. One of the aliases Giles Earl Mabry used in his lifetime was Earl Giles Wilson[42]; there is a record of an operative named Wilson employed by the McCane agency for the Kirby Lumber Company.[43]

On January 6, 1913, Liskie Mabry as a Burns detective was arrested in connection with a plot to kidnap and possibly murder I.W.W. organizer Covington Hall in New Orleans.[44]

The connection of the two Mabry brothers as detectives in the same agencies in the same area more than coincidentally seems to indicate that their undercover employment was underwritten by the Kirby Lumber Company. In this analysis, it appears that the destruction of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers, as well as the destruction of the Farmers and Laborers Protective Association and correspondingly the Socialist Party in Texas, was a conscious effort initialized and orchestrated by corporate interests.

One of the defense attorneys for the FLPA, William B. Atwell (formerly the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Texas and later a federal judge for the Northern District) speculated as much when he stated that the National Association of Manufacturers might have been behind the effort to dismantle the FLPA.[45] In 1911 the President of NAM was John Henry Kirby of the Kirby Lumber Co.[46]

The government conspiracy case against the FLPA soon fizzled.

The government conspiracy case against the FLPA soon fizzled as it proved to be unsubstantiated. Of the hundreds of arrests made in May and June, only 55 indictments were returned. During the month-long trial in Abilene in September, the vast majority of the charges against the FLPA defendants were dismissed. Only three FLPA officers were eventually convicted on conspiracy charges—organizer George T. Bryant, Secretary Samuel J Powell, and President Zeph L. Risely. They were each sentenced to six years imprisonment.[47]

The damage had been done. The FLPA pretty much evaporated, as did the Texas Socialist Party.

Operative Giles Mabry continued his reports. On May 29, according to Agent W. W. Green in Houston, he has reported to the McCane agency and requested that “nobody be sent to Canton to meet him” as “the Lodge in Canton had been disbanded and his source of information cut off.” As an afterthought, Green adds that “Mabry also stated that he was informed that a lot of guns and ammunition was stored at Thurber, Texas.”[48] The Bureau of Investigation on June 2 did not find any “intention on the part of members of the F. & L.P.A. at Thurber to oppose registration and conscription….”[49]

On June 26, Mabry wrote that “some believe that the radical actions of some of the general membership was brought on by German influence.” His report was forwarded to Barnes via the McCane Agency, which suggests he may have still been on the McCane payroll, and implies that he may have been “double billing” the U. S. Government as well the McCane Agency.[50]

Also by June 26, it appeared that the B of I no longer had any immediate need for Mabry’s services. Mabry followed up on that with a telegram stating, “Mabry here. If wanted elsewhere same connection can report.” He was called in to Dallas for a “consultation” as to what might be next.[51]

Following his consultation in Dallas, Mabry, also through the McCane Agency, expressed his willingness to possibly take a position out west, perhaps in Arizona. “An operation there would please me.” But Mabry stated that he would not care to do open work in this case [the FLPA investigations], adding that “covered work would bring the best results.”[52]

Mabry’s willingness to have an assignment in Arizona may have been influenced by the fact that his brother Liskie was then living in Bisbee, employed as a miner[53] and presumably involved in undercover detective work there. The Bureau of Investigation assignment might have been in conjunction with the I.W.W strike against the Phelps Dodge Mining Company. The infamous Bisbee forced deportation of 1186 Wobblies was to begin on July 12, 1917, about two weeks after Giles Mabry’s letter.

It is uncertain whether Mabry did go to Arizona.[54] If he had been “busy with his crops,” as previously stated, he may not have been finished on his farm in time to operate before the Bisbee deportation. For the next few weeks, he continues to send reports concerning the FLPA from Canton using his actual name of G. E. Mabry.

On August 8, he reports from Thurber about how he is unable to obtain any information[55]; his report from Strawn on the tenth is similar.[56] On August 11 Mabry is instructed to proceed to Ft. Worth to meet with the U. S. attorney, presumably in preparation for the FLPA trials[57]; on August 14th Mabry is back in Dallas, tracking down draft resisters[58]; on August 22, there is a report of a conversation with a neighbor.

Mabry’s input with the Bureau of Investigation appeared to be waning in the latter months of 1917. He reported on another conversation with his FLPA neighbor on September 2[59]; Mabry’s report of September 13 to the B of I attempted to revive some of his previous missives, talking about “plans already layed [sic] to blow up rail way bridges and big business in general”, but the person who gives him this information “did not devulge [sic] this mans name” who was the source.[60]

On November 30, he reported on a FLPA fundraising appeal letter for the convicted members of the FLPA, while warning of plots by the “radical element of the Socialist Party.” “I am also acquainted with some of the leading members of the Socialist Party,” he continues.[61\

The Bureau files seem to be silent as to Giles Earl Mabry after this last report. There are some B of I files which talk of an “Operative 100” investigating the alleged prohibited sale of liquor to servicemen in New Orleans in February 1918, and another report on April 24, 1918, from an Operative 100 in San Francisco investigating a “pro-German” dentist, but whether this is Mabry is uncertain.[62]

In 1930 Mabry is in California with his wife Effie and five children, using his “Earl Giles Wilson” alias. He died May 11, 1943, in Imperial, California, and is buried at the Evergreen Cemetery in El Centro[63]. His death certificate and headstone both use his alias.

Earl Giles Wilson/Giles Earl Mabry’s older brother Liskie T. Mabry also continued his migration west to California via Roswell, New Mexico, where his son Liskie Tildon Mabry is born on October 21, 1913. The elder Liskie died in April 1932, and is buried at the Nixon Cemetery in Charleston, Arkansas.[64]

The younger Liskie’s biography is several shades darker than that of his father. He is married several times, and in 1940 he is serving a prison sentence in the California State Penitentiary for a 1936 auto theft. In and out of prison at least seven times, escaping twice, he is convicted in 1967 for the January 2, 1954 murder of North Sacramento Police Officer Francis Rea during a botched burglary and given the death penalty.[65] He is convicted largely on the delayed testimony of his divorced wife, whom he threatened to kill if she divulged the murder of Policeman Rea. His November 12, 1969 execution date was stayed by U.S Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas on October 21 of that year[66] and an appellate court commuted his sentence to life in prison.

In 1975, while in Folsom State prison, he confessed to his complicity in the 1946 murder of his former girlfriend Beddie Walraven, dumping her body in the California desert after taking her diamond wedding ring. He was released from prison in 1981 and he died in Stockton, California in 2002.[67]

Giles Earl Mabry’s career as a private undercover detective operating as a paid informant for anti-union corporate interests most certainly had a devastating effect on the progressive forces of Texas socialism and the Texas labor movement. Even while a war-time hysteria may have influenced attitudes of patriotism in the state, his reports with misleading and nebulous misrepresentations had the additional effect of adding literal fuel to the flames.

As Texas seems to have been one of the first places in the country in which the crackdown on anti-war dissent occurred, it is probably not hyperbole to state that Operative 100’s role in all of this may have served as the prototype for the suppression of dissent in the rest of the nation.

[Steve Rossignol is a retired member of IBEW Local 520, Austin, Texas, and a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). He serves as Archivist for the Socialist Party USA.]

1. The document is stamped “Received May 15th.”

2. “Special Report #101-1917, Farmers and Laborers Protective Association of America. Investigation.” Operative 100 Reports, April 19th, 1917, p.1., Old German Files, Bureau of Investigation, NARA N1085, National Archives.

3. Ibid, p. 4.

4. Ibid p. 5.

5. Ibid.

6. “The Farmers and Laborers Protective Association of America 1915-1917”, Robert Wilson, Master’s Thesis, Baylor University, August 1973, p. 5.

7. Ibid, p. iv.

8. Ibid. p. 9.

9. For more specific information on this, see the Kirby Lumber Company Records, East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas.

10. James E. Fickle, “The Louisiana-Texas Lumber War of 1911-1912,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 16, No.1 (Winter, 1975), p. 60.

11. “Special Report #101-1917. Farmers and Laborers Protective Association of American. Investigation.” Operative 100 Reports, April 21st, 1917. Old German Files, Bureau of Investigation, NARA N1085, National Archives.

12. Wilson, p. 10.

13. Ibid.

14. Labor activists Tom Mooney and Warren Billings were convicted of the July 22, 1916 Preparedness Day bombing in San Francisco, in a case which allegedly involved provocateurs. Mooney was fully pardoned in 1939.

15. “Special Report,” April 21, 1917.

16. Ibid, April 24, 1917.

17. Wilson, p 10.

18. W.W. Green to R.L. Barnes, May 5, 1917, Old German Files, Bureau of Investigation.

19. Ibid.

20. “Letter of S. J. Powell to FLPA Locals,” April 17, 1917, cited in 21. Wilson, p. 13.

21. Wilson, p. 14.

22. B C Baldwin to R L Barnes, May 8, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

23. W C Odell to R.L Barnes, May 7, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

24. R A St. John to R L Barnes, May 5th, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

25. W C Odell to Attorney General, May 15, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

26. C B Anderson, Inspector in Charge, to R L Barnes, May 22, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files

27. Section 5, Selective Draft Law, Public #12 65th Congress, HR 3545, May 18th, 1917.

28. “Staggering Plot of Conspiracy Against the US Discovered”, San Angelo Weekly Standard, May 20th, 1917.

29. A sample of the headlines from the newspapers of the day reflect the media campaign that was waged by the Department of Justice.

30. “The Anti-Conscriptionists,” The New York Times, May 31, 1917.

31. “Special Report. #100-1917, Farmers and Laborers Protective Association. Investigation,” Operative 100, June 8, 1917, p. 2, Bureau of Investigation files.

32. Ibid, also “Special Report”, May 25th, 1917

“Special Report,” Operative 100, July 9th, 1917.

34. W. W. Green to R. L. Barnes, May 23, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

35. James McCane to Robert L. Barnes, June 9, 1917. Also Robert L Barnes to G E Mabry, June 6, 1917. Bureau of Investigation files and R. L. Barnes to Agent Charles Breniman, June 9, 1917. Barnes specifically instructs Breniman to employ Mabry as an individual and not as a member of the detective agency.

36. The East Texas Lumber Workers: An Economic and Social Picture 1870-1950, Ruth Alice Allen, University of Texas Press, 1961, p. 178.

37. Kirby Lumber Company Records, Box 199, Folders 1,2,3,4, et. seq., East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas.

38. C. P. Myers, Manger Mills and Logging, Kirby Lumber Co., to M. L. Alexander, Manager, Southern Lumber Operators Association, February 12, 1912, in the Kirby Papers.

39. Operative 6 Reports, Beaumont, Texas, Saturday 2/3/12, Kirby Lumber Company Papers.

40. The Rebel, Vol. 2, #7, November 2, 1912, p. 3.

41. Operative 3, (E J. Franz), Silsbee, Texas, October 21, 1912. Kirby Papers.

42. https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/115199803/person/270137985065/media/cbe33de9-cbb8-455e-b163-2e019488a734?_phsrc=ysj37&_phstart=successSource, accessed June 24, 2019

43. Kirby Lumber Company papers, Box 199, Folders 1-4.

44. The Rebel (Hallettsville, Tex.), Vol. [2], No. 79, Ed. 1 Saturday, January 11, 1913 – Page: 1.

45. “Say Manufacturers Want to Kill Unions in Texas,” Waco Daily Times-Herald, May 29, 1917, cited in Wilson, p 25.

46. In an address to its 1911 convention, NAM president John Henry Kirby, proclaimed, “The American Federation of Labor is engaged in an open warfare against Jesus Christ and his cause.” — “Violations of free speech and assembly and interference with rights of labor: hearings before a subcommittee.” Seventy-fourth Congress, second session, on S. Res. 266, a resolution to investigate violations of the right of free speech and assembly and interference with the right of labor to organize and bargain collectively. April 10–11, 14-17, 21, 23, 1936, cited in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Association_of_Manufacturers. Accessed June 21, 2019.

47. American Political Prisoners: Prosecutions under the Espionage and Sedition Acts, Stephen M. Kohn, Praeger Publishers, 1994, pp.90, 125, and 127.

48. W. W. Green to R. L. Barnes, May 29th 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

49. Report of Agent Charles E. Breniman, Dallas, Texas, June 3, 1917. Bureau of Investigation files.

50. James McCane to R. L. Barnes, re Operative 100 “Special Report,” June 26, 1917. Bureau of Investigation files.

51. Agent F. M. Spencer to R. L. Barnes, June 26, 1917. Bureau of Investigation files.

52. James McCane to R. L Barnes, re Operative 100 Special Report, June 28, 1917. Bureau of Investigation files.

53. Arizona State Board of Health, County of Cochise, Original Certificate of Birth, State Index #44, January 14, 1917. This would be the birth certificate for Liskie T Mabry’s unnamed daughter.

54. The Bureau of Investigation files contain the report of one “Operative 100” filed in Portland, Oregon, on August 3. G. E. Mabry seems to have been in Texas at this time, as he files several reports from his home town of Canton. Additionally, the style of writing of the Portland Operative 100 does not coincide with that of Mabry.

55. G. E. Mabry to W. E. Allen, Thurber, Texas, August 8, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

56. Ibid., August 10, 1917.

57. Report of Agent Charles E. Breniman, August 11, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

58. G. E. Mabry to W. E. Allen, In Re A E Lowe, Alleged Slacker, August 14, 1917, Bureau of Investigation Files

59. Report of Agent F. M. Spencer, In Re Farmers and Laborers protective Association, September 4, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files

60. G. E. Mabry to C. E. Breniman, Canton Texas, September 13, 1917, Bureau of Investigation Files.

61. G. E. Mabry to Robert L. Barnes, Canton, Texas, November 30, 1917, Bureau of Investigation files.

62. Report of American Protective League #2, February 9, 1918, Bureau of Investigation files; also Reports of February 26 and April 14, 1918.

63. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/187151238/earl-g_-wilson , accessed June 24, 2019

64. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/45632288/liskie-t-mabry , accessed June 25, 2019

65. PEOPLE v. MABRY, Supreme Court of California, In Bank. The PEOPLE, Plaintiff and Respondent, v. Liskie T. MABRY, Defendant and Appellant. , Cr. 11510. Decided: June 26, 1969. https://caselaw.findlaw.com/ca-supreme-court/1825066.html , accessed June 25, 2019

66. “Execution Stay,” Independent Press-Telegram, Long Beach, California, October 21, 1969, p. A-2

67. Greg Hardesty, “Old Bones? Old Guilt? New Mystery”, Orange County Register, October 3, 2011, https://www.ocregister.com/2011/10/03/old-bones-old-guilt-new-mystery/