A shortage of skilled sergeants has led to dubious promotions for inexperienced soldiers — even jeopardizing some operations in Iraq.

By Bill Sasser / July 30, 2008

America’s military commitment in Iraq and Afghanistan is certain to remain a key issue in the presidential race — and soon that could include renewed focus on a “stretched thin” U.S. Army. According to a Salon investigation, the Army is facing a troubling shortage of qualified sergeants, the noncommissioned officers considered to be the backbone of training and combat operations. In fact, a new Army policy intended to boost this critical leadership corps of NCOs has prompted a wave of promotions for apparently unqualified soldiers — and even jeopardized some combat operations in Iraq.

In essence, an Army policy implemented in 2005 and expanded this year lowered the bar for enlisted soldiers with the rank of E-4 to gain the rank of sergeant, or E-5, by diminishing the vetting process. According to more than a half dozen current and former Army sergeants interviewed by Salon, the policy has produced sergeants who are not ready to lead. In some cases, soldiers were promoted even after being denied advancement by their own unit commanders. While awarding a promotion once required effort on the part of a commander, those interviewed say, the Army’s current policy actually requires effort to prevent a promotion, and has had negative consequences on the battlefield.

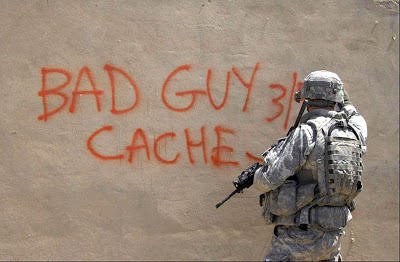

A sergeant interviewed recently at Ft. Hood for this article recounted how he watched his commander feed the promotion papers for one E-4 through a shredder shortly before their unit deployed to Iraq in 2006. After two months in the field, that solider and another E-4 who had also been passed over for promotion were automatically promoted to sergeant anyway, despite their commander’s earlier judgment. Problems soon arose during a combat patrol involving “action on contact,” an encounter with the enemy in which fire is exchanged. “These two NCOs were immature and not ready as far as leading other soldiers, and there were some ‘oh shit’ moments,” said the sergeant, who asked not to be identified and declined to provide specific details about the combat incident because of security restrictions. “We had to have a powwow and pull back on what was going on. Fortunately, no casualties occurred.”

The newly promoted E-5s, he said, also had problems with calling in reports from the field — which, in a combat scenario, could involve such life and death decisions as requesting suppressive fire or determining if an area is safe for medical helicopters to land. “We had to spend a lot of time counseling and mentoring these new E5s in the field,” he said. “They have their sergeant rank and they still have a lot to learn.”

Sgt. Colin Sesek, a medic in the 82nd Airborne Division who returned from a 15-month deployment to Iraq in November 2007, said automatic promotions affected both the morale and effectiveness of medical units in which he served and in combat units he observed. “There was an E-4 in my platoon who was very disorganized and didn’t care about anyone else — he always delegated down the line, even when it was his job to do,” said Sesek. “I’m trying to think of the civilian equivalent of how to describe him — ‘shit bag’ is what we called him. He had been in the Army for a while and boom, he got paper boarded” — a term referring to the Army’s expedited promotions process. “When I heard he got promoted I said, yep, that’s the only way he would have gotten it.”

Sesek said the promotion had wider effects within his unit, as other platoon leaders followed this example and began promoting their own E4s without hesitation. “In infantry platoons, too, I saw people get promoted who shouldn’t have been. The squad leaders told me, ‘Well, if that screwup in that platoon got promoted, then we’ll promote ours too.'”

After six years of war, with multiple tours of duty commonplace, the Army continues struggling to retain and recruit quality soldiers. After failing to meet its recruitment goals in 2005, the Army undertook measures to boost its numbers, with some success. That included stop-loss orders (compulsory postponement of retirements), bonuses of up to $50,000 for re-enlisting, and the loosening of standards on criminal backgrounds, education and age. It also began automatically promoting enlisted personnel with the rank of E-4 to sergeant, or E-5 in the Army’s hierarchy of service ranks, based on a soldier’s time in service, while waiving a requirement that candidates for E-5 appear before a promotions board.

Under the current policy, after 48 months of service E-4s serving in military specialties with shortages are automatically placed on a promotions list. Although a soldier’s name can be removed by his or her commander, each month that soldier’s name is placed back on the list. This was termed “automatic list integration” by the Army (or what the soldiers call “paper boarding”). This April, the policy was expanded to include promotions to staff sergeant, or E-6.

Sgt. Selena Coppa, a communications specialist in the 105th Military Intelligence Battalion, said she has noted a marked lowering of standards for E-4s being promoted to sergeant. “The doctrine now is that you just need to be trainable, and people who are not competent and not good leadership material are being promoted,” said Coppa, who has expressed her concerns through unit performance surveys and spoken directly to her superiors. “A sergeant major told me, ‘Yes, you’re right, but there’s nothing I can do about it.'”

Lt. Col. Elizabeth Edgecomb, branch chief for the Army personnel team at the Department of Defense, explained in an interview with Salon that the Army was short 1,549 sergeants, mostly in combat occupations, when the policy was implemented in February 2005. It has reduced the number of NCO occupational specialties with shortages by 74 percent since then, according to Edgecomb. She added that in many cases promotions are awarded to E-4s who, due to manpower shortages, are already doing the work of E-5s. “The policy does not change Army standards for promotion,” said Edgecomb. “Commanders have the responsibility to stop a potential promotion when they determine a soldier is not trained or is in some way unqualified in accordance with standards.”

Perhaps no part of the U.S. military has carried as heavy a burden in Iraq as Army sergeants, who directly train, mentor, discipline and lead boots-on-the-ground soldiers. After years of war, many of the Army’s most experienced sergeants have retired, left the service, transferred to noncombat posts, or are recovering from battlefield injuries.

“Army NCOs lead on a very personal level and are the backbone of how the U.S. Army is run,” says Lt. Col. Gian Gentile, a former commander in the 4th Infantry Division who teaches military history at West Point. “In combat specialties such as armor and infantry, doing two to three tours is having an effect on NCOs. They have been through a lot and it puts tremendous stress on them and their families.”

The current promotion policy is causing some doubts and bitterness among veteran NCOs. “If these guys don’t work for it and you give it to them, we’re not making leaders, we’re making stripe wearers,” says Staff Sgt. Charles Bunyard, a senior scout in the 1st Cavalry Division at Ft. Hood who commands a unit of Bradley fighting vehicles.

Bunyard has over 15 years of service in the Army, including two deployments to Iraq, where he survived nearly a dozen IED blasts, was grazed in the head by a sniper’s bullet and broke a leg in three places in a training accident. Sent home last year from Diyala province after suffering a dislocated shoulder and a severe concussion in an IED attack, he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. But after healing, he returned to duty and volunteered for a third combat tour. After five months of recuperation, he was cleared by Army doctors to return to duty and has volunteered for a third combat tour.

At Ft. Hood, Bunyard is spending 16-hour days training his squad of new recruits for their first deployment later this year. Married and the father of five children, several months ago he stopped going to his scheduled doctor and therapy appointments, which he says interfered with his duties. “I have a large responsibility to these guys, and when I’m gone I’m cheating them out of leadership and ways to learn better,” said Bunyard, who still has memory problems and sometimes speaks with a slur as a result of his brain injury.

While the Army needs thousands of new NCOs to replenish the existing ranks, thousands more are also needed as the force expands. The Army plans to add 65,000 soldiers to its ranks by 2010, as declared by President Bush in his State of the Union Address in January 2007.

Quality and morale issues notwithstanding, official figures from the Defense Department on re-enlistment show that the Army has exceeded its retention goals for the past three years. But the planned expansion will only increase the Army’s need for NCOs and junior officers, who have also been leaving the military in waves. A shortage of qualified NCOs is tied to a shortage of junior officers, as many choose not to re-enlist in order to move up the ranks by becoming officers, says Gentile. “The Army has holes in its officer corps as well, and enlisted soldiers who would have become NCOs — the cream of the crop — are going to Officer Candidate School rather than becoming sergeants,” he explained. According to Gentile, who served two combat tours in Iraq, it’s now not uncommon to see 26-year-olds with seven years of service who are first sergeants in charge of a platoon of 30 soldiers. Before the war, he says, achieving that rank would have taken twice as long.

Some military experts doubt the force’s capability at present, particularly if it is needed to perform on a third war front. Two former undersecretaries of defense for personnel question the ability of the all-volunteer Army to meet its manpower needs in coming years. “Our volunteer Army was not set up to fight a long war,” says Lawrence Korb, who served in that role in the Reagan administration. “The idea was that an active Army would fight when needed and the National Guard and Reserve were on standby as a ready reserve. They’ve all been in constant rotation for over five years, and we no longer have a reserve. What we’re doing is mortgaging the future of our Army.” Edward Dorn, who served in the Clinton administration, sees trouble on the horizon. “I think an increase of 65,000 by 2010 is out of reach with a volunteer force, unless you have a very significant downturn in the economy,” he said.

Not all E-4s are eager for automatic promotions to sergeant, according to Bandon Neely, who served in a military police battalion at Ft. Hood before leaving the service May 2005. When the policy began in 2005, the Army also had begun to impose stop-loss orders to prevent sergeants from leaving the service, “so a lot of E-4s did not want it,” Neely said. “Guys were being put up for promotion who refused to take it.”

Patrick Campbell, a sergeant in the District of Columbia’s National Guard who was recently awarded an automatic promotion, said he has seen both the benefits and drawbacks of the policy. Campbell, who served as a combat medic in Iraq in 2004 to 2005, said battlefield experience quickly turned new sergeants into competent leaders. “Being in combat forces you to learn fast — your life depends on it,” he said. “At the same time, leadership training is needed but it’s being delayed because of the pressure of deployments. If you promote people without training, what does it mean to be a sergeant?”

John Hagedorn, a sergeant who served in 2007 as a forward observer in the 82nd Airborne Division assigned to an artillery unit in Tikrit, said the high rate of NCO promotions disrupted the chain of command in the platoons to which he was attached. Out of 70 personnel in three platoons, only five soldiers returned without having been promoted to sergeant, he said.

“The artillery soldiers I was assigned to would normally be operating 105-mm Howitzer canons, but most of them had no idea how to fire one,” said Hagedon, 23, who served 15 months in Iraq under stop-loss orders and left the Army after his return in 2007. “The guys who were promoted to E-5 would normally be the crew chief in charge of one of these guns, and when they came home they were thrust into the position where they were untrained in their mission. They would be transferred to other posts and would get somewhere else and not know how to use the gun.”

Sgt. Hagedon’s experience appears to point to another Army problem, documented by an internal Pentagon report co-authored this year by Lt. Col. Gentile. The report, which raises concerns that the Army’s current focus on counterinsurgency has weakened its ability to fight conventional wars, cites among other statistics that 90 percent of Army artillery units are unqualified to fire their weapons accurately — the lowest rating in history.

In Iraq, Sgt. Hagedon said, “All those promotions lessened the significance of being in a position of leadership. It brought junior leaders down to Joe Private level and stole thunder from the older NCOs, who didn’t like seeing all these young guys getting promoted so fast.”

Hagedon said consideration of leadership potential played no part in the promotion process, as the new policy created pressure on senior sergeants to promote, regardless of performance. “If all the other E4s are getting promoted, it will look bad if you don’t promote your guy,” he said. “And if everyone else is getting it, they don’t want to cut an E4 out of the pay raise you get — $200 a month.”

The result in the platoons he observed was a breakdown in the chain of command, which followed the soldiers home: “There was really no difference between the enlisted guys and the junior leadership [in Iraq]. They’re hanging out together, being buddies, not like back in the U.S. where the NCOs are constantly correcting soldiers of a lesser rank. Then you come home to a training environment like Ft. Bragg and it’s a problem. You can’t be hanging out drinking beer with the enlisted guys one night and chewing their ass out the next morning. You end up showing favoritism.”

Such concerns may be exacerbating morale problems caused by multiple deployments. In Hagedon’s own platoon of forward observers, part of the 82nd’s Headquarters Division, only two out of 12 sergeants chose to remain in the Army when their enlistment ended.

Sgt. Major Tom Gills, chief of Army enlisted promotions, says that the current policy has returned promotion rates to what the Army had prior to the end of the Cold War. “Over the years, individual units had adopted their own standards that were higher than official standards,” he said. “A lower and lower percentage of soldiers were going before promotion boards. Through the 1980s, 25 percent of soldiers were going up for promotion, while until recently only 5 percent were coming up for promotion.”

But Andrew Bacevich, a retired Army colonel who served in Vietnam and now teaches U.S. military history and foreign policy at Boston University, said soldiers in the all-volunteer Army will continue to be overtaxed, even with the planned expansion. The strength and morale of noncommissioned officers, he said, has always been a critical measure of the Army. “When the Army began to fall apart during Vietnam one of the red flags was the deterioration of the NCO corps,” said Bacevich. “Experienced NCOs began leaving in large numbers, and the Army tried to make up for it with ‘shake and bake NCOs’ — enlisted men who went through a 90-day school. It didn’t work very well and it didn’t stop the erosion.”

Bacevich, whose son, 1st Lt. Andrew J. Bacevich, served in the 1st Cavalry Division and was killed in Iraq in 2007, added, “We don’t have an Army that is large enough to continue with this sustained rate of deployment, particularly if some other conflict arises elsewhere. The best solution I see is to lessen our commitments abroad.”

Source / salon.com