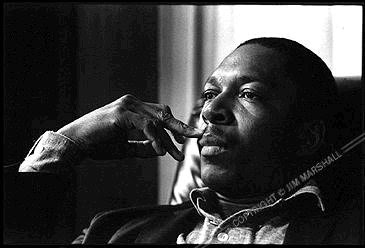

‘A force which is truly for good’:

John Coltrane and the jazz revolution

By Terry Townsend / October 7, 2010

“You can play a shoestring if you’re sincere.” — John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (abbreviated as “Trane” by his fans) was born on September 23, 1926. Since his untimely death on July 17, 1967, saxophone colossus Coltrane has become an icon of African-American pride, achievement, and uncompromising determination. He led a revolution in music that mirrored the turbulent growth of black militancy and revolutionary ideas within the urban black community. Today, Trane continues to inspire.

Coltrane has often been likened to Malcolm X. U.S. jazz writer and socialist Frank Kofsky, in his classic 1970 book Black Nationalism and the Revolution in Music (Pathfinder Press, New York), wrote:

Both men perceived the reality about [the USA] — a reality you could only know if you were Black and had worked your way up and through the tangled jungle of jazz clubs, narcotics, alcohol, mobsters…

Both men called upon their followers to break out of accustomed ways of thinking and feeling, and they themselves were willing to lead the way by challenging all the conventional assumptions and discarding those that failed to meet the rigorous test of reality — even if, in doing so, they were forced to sacrifice their own material security.

Both men could have assured themselves of lives of relative comfort and wellbeing merely by making a few seemingly minor compromises; yet both refused to exchange a mess of consumer-goods pottage for the right to seek after and enunciate the truth as best they could.

It is no accident that references to Coltrane appeared in the films of Spike Lee — most prominently in Mo’ Better Blues but also in Malcolm X. That film features the haunting composition “Alabama” — written by Coltrane after reading a speech by Martin Luther King eulogizing four black children blown up in a racist attack on a church in 1963.

African-American culture often reflects the political and ideological moods and aspirations of the community from which it springs. It sometimes anticipates them. Coltrane’s music evolved during a political upsurge of the African-American people.

Through the late 1950s and into the ’60s, the momentum of the civil rights movement gathered pace. In the cities, the militant ideas of black nationalism and black power were embraced by larger and larger numbers of African Americans. Black youth were fired up by the struggles of their compatriots in the South and the liberation movements in Africa and the Third World.

A significant number discovered the works of Lenin, Mao, Castro, Nkrumah, Fanon, and Ho Chi Minh. This powerful movement for freedom combined with, and inspired, the huge anti-Vietnam War movement and women’s liberation movement to spark a massive youth radicalization that shook U.S. society.

There was also a vigorous cultural radicalization. Many African Americans explored art, music, culture, and religious and philosophical ideas from Africa and Asia that they felt were more in tune with their aspirations and desires. Others set about rediscovering their African heritage and history. It was a period of turbulence, impatience, excitement, frustration, and determination to create a better society.

John Coltrane provided the jazz soundtrack of the ’60s. Anybody who has attempted to come to terms with Coltrane’s music is immediately struck by its brooding impatience, absence of compromise, and sense of a tenacious quest for an undefined goal.

Coltrane’s musical quest began in earnest when he joined Miles Davis in 1955, played for a period with Thelonious Monk in 1957, and rejoined Miles in 1959. In this period, it was clear Coltrane was champing at the bit to break free of the constraints of the now accepted conventions of the previously avant-guard form of jazz, be bop (which itself had developed in the early 1940s among mostly African American musicians as a rebellion against the commercial homogenization of big band “swing” jazz).

His celebrated “sheets of sound” were first heard as his sax solos raced faster and faster, cramming notes into each other to create harmonies of fascinating complexity. His surging solos built around recurring motifs are prominent on Mile Davis’ forever fabulous Kind Of Blue. His recording debut as leader in 1959 with Giant Steps, soon followed by My Favorite Things, found him beginning to explore improvisational freedom.

By 1961, the classic Coltrane quartet was in place — McCoy Tyner on piano, Elvin Jones on drums, and Jimmy Garrison on bass. With this band Trane created some of his greatest work. From 1961 to 1965, they explored new terrain in improvisation as they attempted to extend beyond the limits of bop. They investigated adventurous new polyrhythms and tempos borrowed from African, Arab, and Indian music.

Taking up soprano saxophone allowed Trane to focus on “Eastern” tonalities. He studied sitar and began writing to the great Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar. He experimented with drone instruments and chants. He investigated the use of unusual combinations of instruments to replicate the sound and texture of African and Indian music.

Yet as he experimented, he continued pushing and accentuating his characteristic dense, surging, complex sax lines. Albums such as Coltrane, John Coltrane Quartet Plays and A Love Supreme are great examples of this period.

By 1966, Coltrane’s ceaseless search for musical “progress” led to the demise of his classic quartet with the departure of Jones and Tyner. As far as they had traveled with Trane, they were not prepared to follow their leader further into the uncharted waters he was now exploring.

Respected Australian jazz critic Gail Brennan aptly described the music that followed the quartet’s disintegration, until Coltrane’s premature death from liver cancer at the age of 40, in OK Music magazine: “Some, but not all of the music of Coltrane’s last period pushes emotion, energy, sheer momentum and rhythmic, textural and harmonic complexity to the point where it seems that it can only seize up or explode’.”

Coltrane had been increasingly drawn towards the emerging generation of radical young black musicians who were abandoning the accepted rules of be bop and hard bop jazz to play “free jazz’.” Coltrane was soon seen as the leader of this iconoclastic movement, the first among equals of players like Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, Pharaoh Sanders, Archie Shepp, Eric Dolphy, and Cecil Taylor. Sanders, Shepp, and Dolphy played with Coltrane’s band prior to Jones’ and Tyner’s departure.

Coltrane never explicitly embraced black political black militancy or radical politics but was uncompromisingly in the vanguard of the cultural and spiritual radicalization that was political black nationalism’s constant companion. He buried himself in books on Indian, Asian, and African philosophies and African history — topics which recur regularly in the titles of his songs. His music was a source of black pride and consciousness.

Yet Coltrane was not opposed to radical politics nor was he apolitical. Many of his later musical collaborators were convinced radicals. Free jazz was considered to be the musical equivalent of the radical black politics. Archie Shepp said in 1968: “We are only an extension of that entire civil rights-Black Muslim-black nationalist movement that is taking place in America. That is fundamental to the music.” His saxophone, Shepp added, was “like a machine gun in the hands of the Viet Cong.”

It was not unusual for Coltrane’s performances to attract political crowds. According to one patron at New York’s Half Note club, young blacks would shout “Freedom Now!” as Trane’s long solos reached their climax.

Coltrane was an admirer of Malcolm X. He agreed to play benefit concerts for civil rights organizations, and many compositions were dedicated to Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement. He opposed the Vietnam War.

In 1966, Coltrane told Frank Kofsky:

Music is an expression of higher ideals… brotherhood is there; and I believe with brotherhood, there would be no poverty… there would be no war… I know that there are bad forces, forces put here that bring suffering to others and misery to the world, but I want to be a force which is truly for good.

John Coltrane was responsible for some of the most beautiful, controversial, and challenging music ever created, as is well illustrated by two brilliant albums. Bye Bye Blackbird is a live concert recording made in Europe in mid-1962 consisting of two fantastic, surging 20-minute work-outs. First Meditations was recorded in late 1965 in the twilight of Coltrane’s classic quartet. While it precedes much of his most extreme work, its mystical, turbulent power is hypnotic.

If you have not listened to John Coltrane, these albums are as good a place to start as any. But be warned: experiencing the magic and tumult of Coltrane’s later music is not for the faint-hearted, but it is a challenge well worth meeting.

The militant and the mystic

John Coltrane’s music evolved as black America moved from the optimism sparked by the political and social gains of the mass civil rights movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s, through the mid-’60s explosion in black pride and militancy, to the late ’60s era of “black power’.”

From the mid-’60s, the optimism began to falter. The promise of equality evaporated as the cities and ghettos became increasingly run-down and the reality that the U.S. system was racist to the core became obvious. The militant ideas of “black nationalism,” black power, and socialism were embraced by large numbers of African-Americans as they sought solutions outside the system.

Coltrane’s music was the jazz soundtrack of black radicalization. Coltrane’s classic quartet — with McCoy Tyner on piano, Elvin Jones on drums, and Jimmy Garrison on bass — from 1961 to 1965 was in the vanguard.

But by 1966, Jones and Tyner were not prepared to follow their leader further into uncharted waters. Coltrane increasingly was drawn towards a younger generation of radical young black musicians who were abandoning the accepted rules of jazz to play avant-garde or “free jazz’.”

Archie Shepp and Pharoah Sanders soon became Coltrane’s most regular and important collaborators — at live gigs and on records — until his untimely death in 1967. As these brilliant ’60s reissues prove, they were capable of startling work in their own right.

Between them, Shepp and Sanders personified the two allied streams of black radicalism in jazz in the late ’60s — the political and the spiritual. As U.S. socialist Frank Kofsky pointed out in 1970, both trends reflected the black ghettos’ “vote of `no confidence’ in Western civilisation and the American Dream’.”

Politically, black youth were fired up by the civil rights struggles in the Southern states, the liberation movements in Africa and Asia, and the struggle to end the Vietnam War. The ideas of Marx, Lenin, Mao, Castro, Ho Chi Minh, Kwame Nkrumah, Franz Fanon, and especially Malcolm X were popular. Revolution was openly espoused.

There was also a vigorous cultural radicalization. African Americans explored art, music, and religious and philosophical ideas from Africa and Asia. They set about rediscovering African history. It was a period of turbulence, impatience, excitement, frustration, and determination to create a better society.

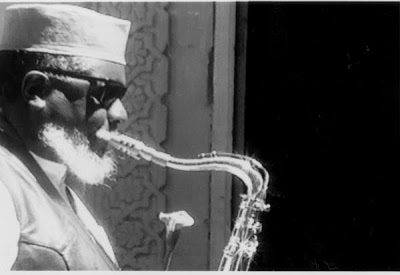

Shepp embraced political black nationalism and Marxism while Sanders, like Coltrane, was uncompromisingly in the vanguard of the cultural and spiritual radicalization.

Fire Music, released in 1965, was Shepp’s second Impulse album. Every track radiates warmth and determination. It has a horn-laden big band feel without any of the staidness that tag implies. While challenging many preconceived notions of jazz, it is thoroughly accessible. Shepp’s tenor sax exudes a rich, hoarse tone that can move from “down and dirty’,” to plaintive, to insistent in a single tune.

The album conforms to Shepp’s 1968 statement that free-jazz musicians were “an extension of that entire civil rights-Black Muslim-black nationalist movement.”

Fire Music opens with “Hambone’,” a tribute to African-American folk music — gospel and blues, and a touch of r&b. The simple melodies contrast with soaring solos and complex rhythms. The album also closes with a mind-boggling live version. “Los Olvidados (the forgotten ones)” is about the frustration Shepp felt when employed as a counselor with a government-funded program aimed at reducing “juvenile delinquency” in New York. The program was under-resourced and was simply a band-aid which, said Shepp, allowed the wealthy and powerful to “assuage their own guilt about the forgotten ones’.”

“Malcolm, Malcolm, Semper Malcolm” is a moving, moody eulogy to the radical black leader Malcolm X, who was assassinated that same year. Shepp, with sax and poem, conveys respect, love and anger while David Izenzon’s beautiful bowed bass “sings” along. It was first composed as part of “The Funeral’,” a longer composition dedicated to murdered Southern U.S. civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

“I call it ‘Malcolm forever’ because [although Malcolm] was killed, the significance of what he was will grow. He was the first cat to give actual expression to much of the hostility most American Negroes feel. A further significance of Malcolm was that toward the end of his life, he was evolving into a sound political realist’,” Shepp explained.

Pharoah Sanders’ radical egalitarian cosmic mysticism, which also characterized Coltrane’s last years, is central to Tauhid (1967) and Karma (1969). Sanders seems to begin where Coltrane left off. Like many other African Americans, he sought to go beyond the hypocrisy of mainstream white Christianity and philosophy to find a creed that was inclusive, non-discriminatory, and tolerant. Finding none, he invented his own.

Karma best illustrates Sanders’ utopian outlook. “The Creator Has a Master Plan’,” a majestic 32-minute opus not unlike Coltrane’s seminal “A Love Supreme,” is both deeply melodic and “caconophonic’.”

Sanders lures the unsuspecting listener with a beautifully conventional introduction which gently leads to his trademark wild and wonderful screams, squalls, squeaks, and growls, all the time softened by the soothing background pulse of bells, shaker, and percussion. Sanders’ world view is summed up by the chant that pervades “Creator”: “Peace and happiness for every man, through all the land.”

Tauhid concentrates on the historical and spiritual heritage of African Americans. “Upper and Lower Egypt” is the product of Sanders’ long research into the history and religions of Egypt. Using the unusual-in-jazz piccolo, Sanders glides through the Lower Nile, moving deeper into Africa. Once in the upper reaches, the mood changes with energetic, chant-like cadences that make the hairs rise on the back of your neck.

Archie Shepp’s political radicalism led to a falling out with Impulse, and he found it extremely difficult to persuade other U.S. record companies to record him. Instead, Shepp taught music at the University of Massachusetts after 1978. Sanders, his radicalism being far less threatening, continued to record and perform. Neither compromised.

What makes these artists great — as all the albums mentioned above reveal — is not simply their immense musical ability, but the fact that they drip with passion, honesty and commitment. Check them out.

Source / International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

The John Coltrane Quartet (John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, Elvin Jones) on the 1963 TV program, Jazz Casual, playing “Alabama,” written by Coltrane after reading a speech by Martin Luther King eulogizing four black children blown up in a racist attack on a church in 1963.

Thanks to Carl Davidson / CCDS / The Rag Blog