The New Geography of Trade: North America Doesn’t Exist

By Laura Carlsen / July 8, 2008

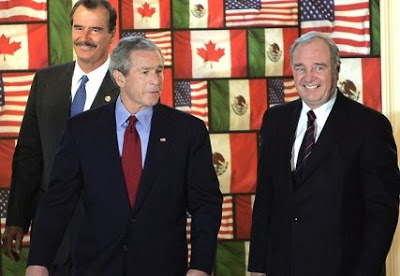

About every six months or so, the media provide a fleeting show of North American unity. Whether on the shores of the Mexican Caribbean, the forests of Quebec, or the hurricane-torn streets of New Orleans, the script is pretty much the same. It includes a lot of back-slapping and almost no public information.

These encounters—the trilateral summits—would be imminently forgettable if not for what happens behind the photo ops.

Business leaders and government officials from the United States, Canada, and Mexico have been meeting to expand on the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement since the trinational summit in Waco, Texas in March of 2005. Ostensibly, the premise is that this great continent of three nations must bond to create a safe, free, and prosperous haven in a threatening world.

The only problem is, North America—at least as portrayed in the summits—doesn’t exist.

Flunking Geography

There is a North American land mass—a fact confirmed by any one of the 515 million people who at this moment are compelled by gravity to stand, sit or lie upon it. But nobody can even agree on its borders.

To the North, the mass breaks up into a vast expanse of ice, impossible to draw on a map as its boundaries recede due to global warming. This is creating consternation and confusion—and not just among polar bears. For the first time since modern science began recording, the fabled Northwest Passage that connects Asia and Europe via North America is free of ice, causing an international dispute over who controls it.

The confusion is even worse regarding the southern edge of our shared continent.

Children in the United States are taught that the North American continent begins in the North—which is always the “top,” passes through a gray area called “Canada,” to reach a vibrant, multi-colored zone divided into 50 states that most good students can name. It then begins its decline, gradually petering out below the Rio Grande. If the kids were to ask their parents where the southern limit is, they too would probably just shrug.

Mexican school children, however, will answer immediately that there really is no North America. They are taught that North and South America are a single continent—”America,” without the “s.” That’s why if you say you’re “American,” they will reply, “But what country are you from?”

Turning to the experts, most geographers have decided that North America extends down through Panama. (To make matters worse, Panama used to be part of South America when it belonged to Colombia, but that’s another story). That means that North America encompasses 23 sovereign nations and 16 colonies, or “dependencies” as they are referred to in this not-so-post-colonial era.

So why this brief geography lesson? Because the ongoing geographical debate offers important insights into what’s wrong with the North American Free Trade Agreement and the son-of-NAFTA—the Security and Prosperity Partnership (SPP).

The problems of defining the region begin with geography, but they get way worse when politics, economics, and culture are thrown in.

Commercial Bloc-heads

The “North American Free Trade Agreement” is actually a compound misnomer. The “North America” in NAFTA is an invention of a particular point in history and a particular set of economic and geopolitical motivations.

“Trade” under the agreement has been liberalized but is far from “free.” Politically powerful sectors in the United States maintain protections, whether openly in the form of tariffs or covertly as phytosanitary barriers or subsidies. All countries maintain some barriers for strategic sectors and products—often a reasonable practice, especially in the case of developing countries like Mexico.

Finally, the “agreement” did involve the Congress and civil society organizations at the moment of approval in the United States, but in the negotiating stages and certainly in Mexico, civil society was shut out of the process. NAFTA’s extension into the SPP was even more non-consensual since it did not involve congressional approval or signed agreements. In Mexico, NAFTA isn’t legally an agreement but rather a treaty, giving it a higher juridical stature than in the United States.

But the biggest problem here is the assumed commonality of interests. The most touted rationale for NAFTA is that the United States, Canada, and Mexico must join to form a trade bloc to compete in the global market with other trade blocs. This assumes that the three nations are on the same team. The Security and Prosperity Agreement even formed a “North American Competitiveness Council” made up of Walmart, Chevron, Ford, Suncor, Scotiabank, Mexicana, and other major corporations to represent the team interests.

But when we look at the play on the field, there is very little teamwork involved. In multilateral forums each country plays by its own game plan. In the World Trade Organization, Mexico forms part of the Group of 20 to protest U.S. and Canadian agricultural subsidies. Canada and the United States have faced off on numerous trade conflicts among themselves, many of them—like the softwood lumber case—the subject of drawn-out and bitter negotiations. Mexico has also had disputes with its supposed team mates, including the tuna-dolphin dispute, the entry of Mexican trucks into the United States under the agreed-to terms of NAFTA, and the tomato wars between northern Mexico and Florida.

If the bloc fails to act as a bloc of nations on the international level, its lack of cohesiveness is even more obvious from the point of view of its major corporations. Globalization opens up a world where everyone is out for themselves in search of cost-cutting production, cheaper resources, and closer markets. Corporations based in the United States, Canada, or Mexico have no loyalty whatsoever to building North America as a competitive bloc. An executive of a Hewlett-Packard subsidiary described how the company decided to move operations from the Mexican border to Indonesia. It was a no-brainer, he said, the labor was cheaper and it was closer to the expanding Chinese market. Like a game of Chinese checkers, the company now seeks to leap production from Indonesia directly into China as its next strategic move. NAFTA partner Mexico is left with nothing but unemployment.

Even the most regionally integrated industries, like the auto industries, measure their success not in terms of integration but by how successfully they can break down the production process into ever-cheaper components. This allows them to offshore labor intensive phases to Mexico where labor is cheap, while maintaining sales and research, management, and research and development in the United States. If anything changes in that formula, the whole concept of regional integration would be thrown out the window in search of a different global strategy. Recent negotiations to reduce wages in Mexican auto plants of Ford and General Motors based on the threat to move production to China are good examples of the logic.

Although corporate strategies are global not regional, corporations do have a reason to push the NAFTA-SPP agenda. Corporations that have operations in the three nations have an interest in developing mechanisms to lower all costs and barriers. In this sense they seek to create not a trade bloc to compete against their operations in other countries, but a pilot project for territorial reorganization along the lines of a corporate wish list. In this conception, “North America” is not a block of countries defined by a common geography and purpose, so much as a territory delineated for the optimal use of capital.

This realization explodes the first myth of “regional integration” under NAFTA. Far from a homogeneous process of integration, it promotes a curious blend of integration and fragmentation of territory. Mexico, for example, has been split in two. The North, where irrigation, climate, and topography provide advantages in agriculture and industrialization is more advanced, is tightly integrated into the U.S. economy. U.S. companies selling in U.S. markets now control much of production and Mexican export companies are concentrated in this region.

Southern Mexico remains outside this scheme and always will. Even the World Bank has recognized this in a study called “Why NAFTA did not reach the South.” The response is the Plan Puebla-Panama, with a focus on public-sector loans for major infrastructure development, resource extraction, and energy grids. Since the region is too indigenous, too remote, and too rebellious for productive investment, the southern states of Mexico have been shunted off to join Central America as a facilitator region to provide natural resources and serve as a conduit for the North-South movement of goods. The local populations are considered largely extraneous.

Security for Who?

The issue of security is where the myth of a unified North America is most starkly revealed. Security didn’t figure into the original NAFTA agenda, although it was implied that greater economic integration would result in harmonization of foreign policy agendas. Sept. 11 and the Bush National Security Doctrine created a strong U.S. security agenda while at the same time creating tensions with the NAFTA partners.

Canadian business sought to avoid another border closure like the one following the World Trade Center attacks and was willing to concede on other issues to assure uninterrupted trade. The government was forced to accept U.S. Homeland Security measures such as a “no-fly” list that bars “suspect individuals,” including dissidents, from air travel between the two nations.

The Mexican people, as in all of Latin America, reacted to U.S. unilateralism and the invasion of Iraq with a rise in anti-American sentiment and suspicion. But both National Action Party (PAN) presidents Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderon shared much of the Bush agenda and have entered into commitments under the SPP on security issues.

The security plan put forth in the SPP is an extension of the agenda of a nation that is the world’s pre-eminent military power, a major target for international terrorist attacks, a proponent of unilateral action and pre-emptive strikes, and an advocate of military over diplomatic responses and U.S. hegemony the guarantee of global governance.

Mexico is a nation that is not a target of international terrorism, has had a foreign policy of neutrality, and whose primary security threat has historically been—the United States. Nonetheless, Mexico has had to accept the failure of the binational immigration reform agenda and cooperate in aspects of the U.S. Homeland Security agenda and other counter-terrorism programs. The latest and most radical project to come out of the SPP security agenda is Plan Mexico, or the Merida Initiative—a regional security plan developed in the context of the SPP that bundles counter-narcotics, counter-terrorism, and border security measures into a new national security program for Mexico led by Washington.

The concept that Canada, the United States, and Mexico should forge a single security agenda as a non-existent continent is absurd and dangerous. Yet this is exactly what the SPP does. It is an agreement built on a convenient myth, a partnership that really consists of two countries subordinated to a superpower that agree to this subordination due to economic dependencies and the interests of corporations that cross borders seeking to maximize profits.

The New Geography

When the North American Free Trade Agreement was conceived, it was not a trinational—much less continental—affair. The negotiations focused on pasting together three separate agreements: the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement—already in effect since 1989, a new U.S.-Mexico agreement and, to a lesser degree, a series of Canada-Mexico rules.

Few people realize that the resulting NAFTA reflects these differences. Critical goods for the United States, such as oil and corn, are traded under completely separate rules with Canada and with Mexico in the context of NAFTA depending on the relative bargaining power.

What has happened in the 14 years since NAFTA has fractured the continent even more. Led by the transnational corporations for whom it was designed, in practical terms NAFTA today covers an expanse of territory that runs roughly from Mexico City in the south, to mid-Canada. Through a growing network of consolidated production chains, trade links, and infrastructure development, this region—with the exception of poverty zones of little interest for capital expansion—has undergone rapid processes of concentration and integration.

Under the “vision” of North America forged under NAFTA and its follow-up, the Security and Prosperity Partnership, the three governments have attempted to convince their people that their fate lies along a common path—a path defined by geography, cemented by shared values, and marked by the assumption that just one road leads to the fulfillment of everyone’s goals. But it has become increasingly clear that instead of being a pact between three nations, NAFTA constitutes a roadmap for U.S. regional hegemony.

Not So Fast …

Right wing organizations like the John Birch Society that have been up in arms over the supposed creation of a North American Union and the construction of NAFTA superhighways, may find comfort in the thesis that North America doesn’t—and shouldn’t—exist. But just because I argue that each nation must define and defend its public good, doesn’t mean I agree that there is a neo-Aztec conspiracy to take over the United States. The greatest threat to every country in the region is the attempt of the Bush administration to impose its failed trade and security agenda at home and abroad, and the supranational powers of transnational corporations.

Should We All Go Home Now?

The question remaining is: if North America doesn’t exist, why should Canadians, U.S. citizens, and Mexicans work together to shape the NAFTA and SPP processes?

The trinational networks that have formed to monitor and question both NAFTA and the SPP play a critical role. Although each nation has its own priorities and demands, the networks serve to share information and compare notes on how regional integration affects citizens’ interests.

Grassroots organizations from the three countries face common challenges and common threats. The indisputably high levels of trade, investment, immigration, and cultural exchange that exist between our countries mean that we live daily lives that overlap across borders. Maybe it isn’t a region or a trading bloc in the terms conceived of under the SPP and the differences between us are many and a source of strength. But we are neighbors—as nations, as communities, and as families.

These organizations, meeting in binational or trinational conferences and to protest at official summits, explode the myth of regional homogeneity while at the same time making common cause. They expose the lie that there is only one path forward by developing alternatives in policy and practice. Precisely on the basis of their different political contexts and geographical, ethnic, and economic diversity, they have the potential to build a crossborder movement for social justice to counteract plans for regional integration designed and implemented exclusively in the upper echelons of business and government.

Fourteen years after implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, a majority of the population in all three countries believes the agreement has had a net negative effect on their nation and it turns out that the North American Free Trade Agreement is a misnomer in every one of its terms—it wasn’t an agreement, it isn’t free trade, and North America doesn’t exist. So now what?

First, stop extending it. The SPP must be thoroughly reviewed and revamped. Most likely this review will lead to construction of different forums for trinational coordination that separate the trade/investment and security areas, balance out the preponderant influence of the United States government, and open up proceedings and representation to the public.

Second, stop copying it. Although NAFTA is the only trade agreement to extend into an SPP, the Free Trade Agreement model enshrined there has become a template for other agreements and, in the case of the United States, pressures to impose security plans tend to follow close behind. The Merida Initiative contains resources for Central American countries to integrate the CAFTA region into the regional security plan.

Finally, analyze and evaluate the SPP—the forces behind it, the decisions it makes that affect us, and the directions it plans for the future. Citizens have the right and the obligation to know about and participate in mapping the future, and when they do it’s likely to look far different from the future mapped for us by corporate and government leaders behind the closed doors of the Security and Prosperity Partnership.

[Laura Carlsen (lcarlsen(a)ciponline.org) is director of the Americas Policy Program in Mexico City. This piece was part of a talk at the Lessons from NAFTA Conference. Check out the Americas Mexico blog at http://www.americasmexico.blogspot.com/.]

Source / Counterpunch

The Rag Blog