Stoney Burns dies at 68:

Crusading underground journalist

was incessantly harassed by Dallas officials

By Thorne Dreyer / The Rag Blog / May 2, 2011

See “Stoney Burns used a gentle wit to fight injustice in Dallas,” by James McEnteer, Below.

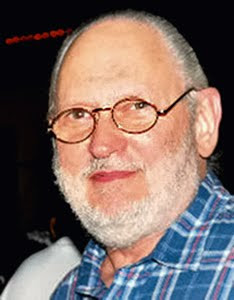

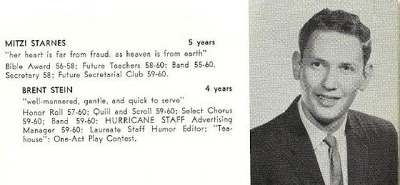

Stoney, who was born Brent LaSalle Stein, was a Sixties activist/journalist and pioneer of the underground press in Texas. When we were publishing The Rag in Austin and Space City! in Houston, he edited a series of publications in Dallas, including Dallas Notes and the Iconoclast — and later the music magazine, Buddy. In its notice about Burns’ death, Pegasus News referred to Stoney as the “King of the Hippies.”

In an April 29 article, The Dallas Morning News said that Burns’ Dallas Notes “decried war, intolerance and hypocrisy with a playful aggression and a cutting edge.”

In his 1992 book Fighting Words, in which he profiled five independent Texas journalists, James McEnteer wrote, “Powered by an anarchic energy and a highly developed sense of the absurd, Stoney personified everything official Dallas loathed.” [See McEnteer’s reflections on Stoney Burns, written for The Rag Blog, below.]

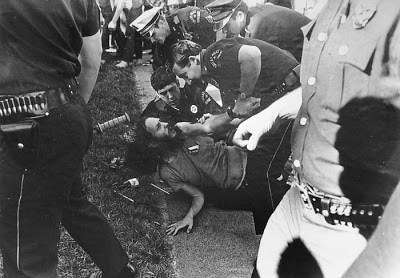

Stoney was incessantly harassed by the Dallas authorities, who charged him with obscenity, beat him mercilessly, tore up his offices, and confiscated his equipment.

Burns’ obscenity case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court where Justice William O. Douglas commented on the cops’ ransacking of the Dallas Notes offices: “It would be difficult to find in our books a more lawless search-and-destroy raid.”

Stoney had trouble finding anyone in Dallas to print his newspapers, and, according to Austin’s Steve Speir, a potential printer in Fort Worth backed out after someone threatened to burn down his shop. So Steve set Stoney up with a printer in Waco, “and on the way back to Dallas we’d be stopped by the cops and harassed. They’d throw all the papers on the ground and search the truck.”

According to The Rag Blog’s David P. Hamilton, four Dallas police cars followed him for several miles after one visit to Stoney’s home.

In 1974, Time Magazine wrote, “The law in Dallas, from all appearances, had been bent on getting Stoney Burns for years” when they “found in the glove compartment a tiny stash of marijuana. It was barely enough for one or two joints.” But it was enough to get Stoney a sentence of 10 years and one day — time he never served thanks to Texas Governor Dolph Briscoe who commuted the sentence.

Angus Wynne told the Dallas Observer that Stoney Burns had “gone through so much, between his public battles and private ones, and turned into a sweetheart. He’d had [an earlier] heart attack and cancer and whipped all those… He was just a great guy, one of the generalissimos of the so-called revolution back then. There was something real special about Stoney…”

[Rag Blog editor Thorne Dreyer was a colleague of Stoney Burns in the Sixties underground press.]

Fighting words:

Stoney Burns used a gentle wit

to fight injustice in Dallas

By James McEnteer / The Rag Blog / May 2, 2011

“Maybe that’s why we’re hated. We tell the truth; we’ve got nothing to lose. We do have something to gain, however. It’s our self-respect. Yeah, we tell the truth. It’s about time some newspaper did.”

— Stoney Burns, Dallas Notes [From James McEnteer: Fighting Words, Independent Journalists in Texas, UT Press, 1992.]

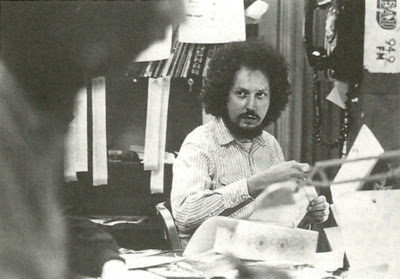

Stoney was not just a brave man — facing down the rigid Dallas Establishment in large part all by his lonesome — but a funny one. He used his gentle wit and sense of the ridiculous as effective weapons for social justice in 1960s Dallas, just about the unfriendliest territory imaginable for stoned longhairs looking to have a good time.

Stoney loved a good time — good music, friends, and laughter. But his easy-going sense of the absurd enraged the humorless conservatives in the Dallas Police Department who considered his satire of local laws and his criticism of usually unmentioned overbearing police tactics as unacceptable threats to their sense of law and order.

Stoney became a cause and a crusader almost by accident, as the sole occupant of the void left by jackboot censorship of all but the most orthodox right-wing cant in the Dallas media.

His Notes from Underground started on the SMU campus and was quickly banned. He was the only journalist to describe and photograph police harassment of peaceful long-haired young people in Dallas parks. His various newspapers took different names over the years, but were always an eclectic mix of music reviews, social commentary, and jokes at the expense of local officials, reflecting Stoney’s own sensibilities.

His papers featured outrageous cartoons, guaranteed to offend the white bread, church-bred Folks who Mattered in Dallas. Stoney always professed bewilderment at the passionate hatred his dopey humor aroused among otherwise rather staid, affectless citizens. The brief, final incarnation of Stoney’s journalistic ambitions was a paper he called The Iconoclast, in homage to the Waco rabblerouser, William Brann.

The police harassed Stoney Burns for years, wrecked his newspaper offices, stole his equipment, planted dope on him, and tried every which way to shut him up, finally hounding him into prison for 10 years and a day on a trumped-up charge of marijuana possession, which the governor later quietly dismissed.

But Stoney’s abbreviated prison term ended up accomplishing its goal of silencing a genuine independent voice of Dallas journalism. Stoney went on to publish Buddy, about the local music scene, but made only occasional, rather vague political comments in subsequent years.

Stoney Burns brought light and fresh air into Dallas public discourse of the 1960s. Despite the strange (to him) resistance his journalism conjured in the authorities, Stoney had the courage to continue telling the truth as he saw it for seven years.

He served as an inspiration to many in his own community and beyond, revealing the cowardice of a system ruled by intimidation, not by public assent. He opened up the acceptable limits of free speech in 1960s Dallas. And he paid a price for it.

Dallas and Texas and the country are in Stoney’s debt, now as then. Stoney’s courage and humor are needed today as much as ever. His spirit will always be worth remembering.

[Rag Blog contributor James McEnteer is the author of Fighting Words: Independent journalists in Texas, published by the University of Texas Press. He lives near Durban, South Africa.]

Also see:

- Stoney Burns, Co-Founder of Underground Paper Dallas Notes and Buddy, Has Died by Robert Wilonsky / Dallas Observer / April 29, 2011

- Ernest McMillan and Stoney Burns : Dallas 60s Activists Revisited by Roy Appleton / The Rag Blog / November 3, 2008

The Rag Blog

I knew Stoney Burns. His papers were often printed by Bill Foster, Jr who inherited a newspaper “The Waco Citizen” from his father. I spoke to him at the “Citizen” office in downtown Waco. He agreed to publish my articles and I still have the copies of the “Notes” they appeared in. Although mild by todays standards, “Dallas Notes” was outrageous and subversive in it’s time. I was dating a Baylor girl who lived in Ruth Collins Hall. In cold months I would smuggle copies of “Notes” into Ruth Collins under my coat and spread them around on the lobby reading table among the pablum newspapers. She later told me the other girls loved it.

The people I most admired on the alternative press scene outside of Austin (which is to say other than family) were Paul Krassner, John Kois of Kaleidoscope, and Stoney. Krassner for iconoclasm on steroids..er, maybe acid..and Kois and Burns for how they stood up to major repression with sharp humor and great courage.

R.I.P.

3/02/2013

Thorne and James McEnteer,

Came to your tribute to Brent just today and it made me feel sad all over again in the re-remembrance of his passing and his courageous battles leading up to –30–. Warmest regards and good wishes for you both. Doug Baker

I worked for Stoney for more than 8 years with him at BUDDY. By then his “activist bent” had been pretty subdued by his stint in Huntsville, but it would surface occasionally whenever he witnessed something he believed to be outright wrong and mean-spirited. It is just hard for me to comprehend that a person could be arrested, beaten and eventually sent to Huntsville (hardly a Club Fed prison) for actions that you can see regularly on MTV or other “reality” TV shows today. He always insisted that the pot was planted on him (“I was so hot that there was no way I would drive a car with dope in it.”). In all my years of knowing the guy, he never victimized anyone. All of his doping, profanity or publishing antics were victimless crimes IMHO. He loved to puncture pomposity and saw the absurd in just about everything that authority figures in Dallas preached. One of his favorite sayings was, “I printed the Iconoclast in Waco, where they believed in freedom of speech, and cash in advance.” He gave several Texas writers their early breaks, like Joe Nick Patoski, Tracy Hayes and Kim Pierce. I can only imagine the fun he would have with Rick Perry and the Tea Party today. Texas could sure use him now. Last time I saw him alive was at a Christmas party at my home. He used to always say, “Let’s put the X back in Xmas.”

The guy made me laugh, regularly, and that’s something we don’t do much nowadays.

Kids today have no idea how dangerous it was to be who you really were in Texas back then. There would be no “alternative press” in Texas today without him. The Dallas Observer should put up a statue to Stoney at their office because they wouldn’t have a market if it wasn’t for him.