Phil Ochs: Sensitive in a parking lot

By Tom Miller / The Rag Blog / February 28, 2011

Show me a prison, show me a jail

Show me a prisoner whose face has grown paleAnd I’ll show you a young man

With so many reasons why

And there but for fortune, may go you or I— Phil Ochs

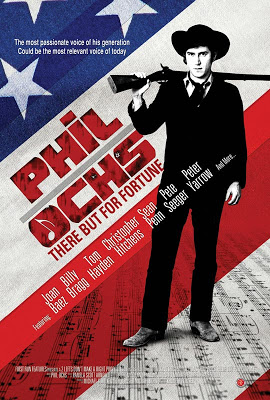

[There But for Fortune, the new documentary about folksinger Phil Ochs, provoked this piece by Rag Blog contributor Tom Miller]

Phil Ochs was singing from the back of a flatbed truck in a Florida parking lot to 80 people at a benefit concert supporting defendants in the 1973 “Gainesville Eight” trial. The eight had been charged with conspiring to disrupt the previous summer’s political conventions in Miami, and Ochs volunteered to sing on their behalf.

The sound system was awful, the afternoon sun was sweltering, and people slowly drifted away. In the middle of Ochs’ poignant ballad, “Pleasures of the Harbor,” a two-ton truck revved up, parting the slim audience as it left. Uninterrupted, Ochs finished the song to light, half-hearted applause. “You know,” he said softly, “it’s tough to be sensitive in a parking lot.”

It was illustrative of Phil Ochs’ life, which ended abruptly at the age of 35 on April 9, 35 years ago. Ochs, one of the prominent topical singers from the fertile Greenwich Village folkie scene of the early ‘60s, carved a niche for himself by consciously blending a politically radical awareness with an appreciation of mainstream American culture.

His was the face you saw on television screens singing at civil rights and anti-war rallies, lending cultural affirmation to what we knew was right. Dry politicos never understood his constant allusions to mythic movieland characters; loyalists booed him at a 1970 concert when he mixed songs by Merle Haggard, Buddy Holly, and Elvis Presley with his own. He exploited this contradiction, seldom losing his socialist vision.

Among his best-known anti-war melodies are “I Ain’t Marchin’ Any More” and “I Declare the War is Over,” But Phil’s perspective was wide, and he wrote about other American misadventures, too, using sarcasm, outrage and irony to clarify confusion and dilute the obvious. As a troubadour he affected the collective consciousness of an era with songs mocking wishy-washy liberals, intervention in Caribbean islands, and political fear.

Ochs occupied a position of major influence in a decade of dramatic upheaval, a role with a rich history in most revolutionary societies. He felt a special kinship with Chilean poet Victor Jara whom he met in a 1972 visit to Chile; it was Jara’s death during Augusto Pinochet’s September 1973 military coup that sparked Ochs’ most ambitious project — organizing a Madison Square Garden concert in support of Chilean refugees and the underground freedom-fighters they left behind.

The concert, a sloppy and joyous affair, included Arlo Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Dave Von Ronk, and scores of others paying tribute to the fallen Allende government. The benefit was a smashing success, raising money and consciousness for the cause, using folk-art as the medium. It was, by his own admission, the high point of Ochs’ life.

One of Phil’s lifetime goals was to visit every country in the world; at the time of his death he was one-third there. He had traveled extensively through Europe and Africa, mixing courtesy calls on music industry personnel alongside meetings with revolutionary forces in the same countries.

It was an intoxicating mix of acquaintances, equaling the engaging blend his own writing produced. He could write moving tributes to migrant labor (“Bracero”) on one album and show self-deprecation (“Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Me”) on another.

Movies played a large part in Phil Ochs’ life and his songs. In his movie-going prime, he took in twenty films a month. For a short while he wrote a movie column for the L.A. Free Press, juxtaposing Marxism with Bruce Lee shows, all of which he had seen. He knew theater schedules in both New York and Los Angeles, where he kept sloppy apartments, and was known to time his flights between the two cities to catch movies within an hour of arrival. Because Arizona churns out “B” movies like few other places, we talked now and then about him coming out for a month just to watch them in production, but it was mainly just talk.

When his career was at its peak, when he played gatherings like the Newport Folk Festival, circumstances wrote his songs. He was in the creative vanguard, maintaining high energy for himself and those he sang for. Less acknowledged but quite good were his nonpolitical works on later albums.

The catalyst for his creativity was the friction produced by civil rights activity and support for countries the U.S. was invading. When that friction took other forms, Phil’s sensitivity remained, but there was little to write about. Sparks of ideas would come and he’d write them in his journal, but no songs came forth.

His record company was content to keep him on, knowing that if he ever wrote again his material would surely be successful. They even printed buttons reading INSPIRE PHIL OCHS. During Watergate he released a 45 rpm record, a remake of his early civil rights song called “Here’s to the State of Mississippi,” with “Richard Nixon” substituted for “Mississippi.” But he wasn’t fooling anyone.

In the two years following the Chile benefit Ochs went through manic-depressive cycles, sometimes obnoxious and arrogant to those he was close to, then retreating into himself for long periods. A few months before he died I found him living at a New York City flophouse. He told me that in the previous months he had been careening around the country in and out of jails under various names, drunk and involved in outrageous scams with unbelievable characters of high and low life.

His name was prominent among those considered for Bob Dylan’s famous Rolling Thunder Review. He had had an off and on relationship with Dylan over the years, but his unpredictability got him axed from the tour before it began.

At this point friends had been suggesting various therapies but he never really followed through. When we spoke last he was living in Queens, Long Island, with his sister’s family, and it sounded like his depression was bottoming out. His suicide a few weeks later ended the pain.

A month after Ochs hanged himself, New York’s Felt Forum filled with thousands of his fans for “An Evening with Phil Ochs and Friends.” As he had at the Allende affair, Dave Van Ronk sang “He Was a Friend of Mine.” After the show, family and friends gathered at a Village bar to toast our friend and brother. We raised our glasses: “There but for fortune,” we agreed.

[Tom Miller’s 10 books include Revenge of the Saguaro: Offbeat Travels Through America’s Southwest.” His web site is www.tommillerbooks.com.]

‘There But for Fortune’ — Phil Ochs, Live at the Bitter End

‘I Ain’t Marching Anymore’ — Phil Ochs

The death of even one good man diminishes all men to some degree, so they say. The death of Phil Ochs transformed the whole damn world into a land of Lilliputians.