A long but very good analysis about the very shaky underpinnings of the US economy. If you think collateralized debt obligations backing up sub-prime loans were a problem, then read about the far bigger problem of collateralized default swaps. It looks like Bear Stearns may be only the first domino to fall. I’ve concentrated some juicy parts from the original article linked below.

Roger Baker / The Rag Blog

Hedge Funds in Swaps Face Peril With Rising Junk Bond Defaults

By David Evans / May 20, 2008

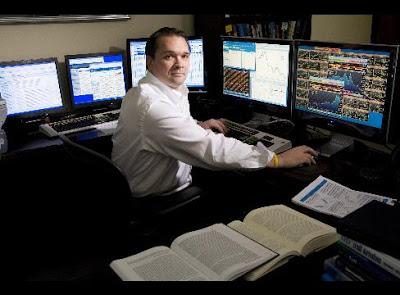

It’s Friday, March 14, and hedge fund adviser Tim Backshall is trying to stave off panic. Backshall sits in the Walnut Creek, California, office of his firm, Credit Derivatives Research LLC, at a U-shaped desk dominated by five computer monitors..

On this day, a CDS-market meltdown doesn’t happen. In a frenzy of weekend activity, the Federal Reserve and JPMorgan Chase & Co. rescue Bear Stearns from bankruptcy — removing the need for the sellers of credit-default protection to pay up on their contracts.

Chain Reaction

Backshall and his clients aren’t the only ones spooked by the prospect of a CDS catastrophe. Billionaire investor George Soros says a chain reaction of failures in the swaps market could trigger the next global financial crisis.

CDSs, which were devised by J.P. Morgan & Co. bankers in the early 1990s to hedge their loan risks, now constitute a sprawling, rapidly growing market that includes contracts protecting $62 trillion in debt.

The market is unregulated, and there are no public records showing whether sellers have the assets to pay out if a bond defaults. This so-called counterparty risk is a ticking time bomb.

“It is a Damocles sword waiting to fall,” says Soros, 77, whose new book is called “The New Paradigm for Financial Markets: The Credit Crisis of 2008 and What It Means” (PublicAffairs).

“To allow a market of that size to develop without regulatory supervision is really unacceptable,” Soros says…

…The Fed was worried about the biggest players in the CDS market, Mason says. “It was a JPMorgan bailout, not a bailout of Bear,” he says.

JPMorgan spokesman Brian Marchiony declined to comment for this article.

Credit-default swaps are derivatives, meaning they’re financial contracts that don’t contain any actual assets. Their value is based on the worth of underlying loans and bonds. Swaps are similar to insurance policies — with two key differences.

Unlike with traditional insurance, no agency monitors the seller of a swap contract to be certain it has the money to cover debt defaults. In addition, swap buyers don’t need to actually own the asset they want to protect.

It’s as if many investors could buy insurance on the same multimillion-dollar home they didn’t own and then collect on its full value if the house burned down.

Bigger Than NYSE

When traders buy swap protection, they’re speculating a loan or bond will fail; when they sell swaps, they’re betting that a borrower’s ability to pay will improve.

The market, which has doubled in size every year since 2000 and is larger in dollar value than the New York Stock Exchange, is controlled by banks like JPMorgan, which act as dealers for buyers and sellers. Swap prices and trade volume aren’t publicly posted, so investors have to rely on bids and offers by banks…

…Banks are the largest buyers and sellers of CDSs. New York- based JPMorgan trades the most, with swaps betting on future credit quality of $7.9 trillion in debt, according to the OCC. Citigroup Inc., also in New York, is second, with $3.2 trillion in CDSs.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley, two New York- based firms whose swap trading isn’t tracked by the OCC because they’re not commercial banks, are the largest swap counterparties, according to New York-based Fitch Ratings, which doesn’t provide dollar amounts…

…Fitch Ratings reported in July 2007 that 40 percent of CDS protection sold worldwide is on companies or securities that are rated below investment grade, up from 8 percent in 2002. On May 7, Moody’s wrote that as the economy weakened, high-yield-debt defaults by companies worldwide would increase fourfold in one year to 6.1percent by April 2009.

The pressure is building. On May 5, for example, Tropicana Entertainment LLC filed for bankruptcy after the casino owner defaulted on $1.32 billion in debt.

‘Complicate the Crisis’

A surge in corporate defaults may leave swap buyers scrambling, many unsuccessfully, to collect hundreds of billions of dollars from their counterparties, says Satyajit Das, a former Citigroup derivatives trader and author of “Credit Derivatives: CDOs & Structured Credit Products” (Wiley Finance, 2005).

“This is going to complicate the financial crisis,” Das says. He expects numerous disputes and lawsuits, as protection buyers battle sellers over the technical definition of default – – this requires proving which bond or loan holders weren’t paid — and the amount of payments due.

“It’s going to become extremely messy,” he says. “I’m really scared this is going to freeze up the financial system.”…

“I think there’s a major risk of counterparty default from hedge funds,” Cicione says. “It’s inconceivable that the Fed or any central bank will bail out the hedge funds. If you have a systemic crisis in the hedge fund industry, then of course their banks will take the hit.”

The Joint Forum of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, an international group of banking, insurance and securities regulators, wrote in April that the trillions of dollars in swaps traded by hedge funds pose a threat to financial markets around the world.

“It is difficult to develop a clear picture of which institutions are the ultimate holders of some of the credit risk transferred,” the report said. “It can be difficult even to quantify the amount of risk that has been transferred.”

Counterparty risk can become complicated in a hurry, Das says. In a typical CDS deal, a hedge fund will sell protection to a bank, which will then resell the same protection to another bank, and such dealing will continue, sometimes in a circle, Das says…

…Michael Greenberger, director of trading and markets at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission from 1997 to 1999, says the Fed is fully aware of the risk banks and the global economy face if CDS holders can’t cover their losses.

“Oh, absolutely, there’s no doubt about it,” says Greenberger, who’s now a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law in Baltimore. He says swaps were very much on the Fed’s mind when Bear Stearns started sliding toward bankruptcy.

“People who were relying on Bear for their own solvency would’ve started defaulting,” he says. “That would’ve triggered a series of counterparty failures. It was a house of cards.”…

…In the calmest of times, making reasoned decisions about swap prices is a challenge. Now, it’s impossible. Traders don’t have access to any company data more recent than Bear’s February annual report. Sharp-eyed investors looking through that filing might have spotted a paragraph that’s strangely prescient.

“As a result of the global credit crises and the increasingly large numbers of credit defaults, there is a risk that counterparties could fail, shut down, file for bankruptcy or be unable to pay out contracts,” Bear wrote…

…When it bailed out Bear Stearns, the Federal Reserve effectively deputized JPMorgan to monitor the credit-default- swap market, says Edward Kane, a finance professor at Boston College. Because regulators don’t know where the risks lie, they’re helpless, Kane says.

Default swaps shift the risk from a company’s credit to the possibility that a counterparty might fail, says Kane, who’s a senior financial Research.

‘Off Balance Sheet’

“You’ve really disguised traditional credit risk, pushed it off balance sheet to its counterparties,” Kane says. “And this is not visible to the regulators.”

BNP analyst Cicione says regulators will be hard-pressed to prevent the next potential breakdown in the swaps market.

“Apart from JPMorgan, there aren’t many other banks out there capable of doing this,” he says. “That’s what’s worrying us. If there were to be more Bear Stearnses, who would step in and give a helping hand? You can’t expect the Fed to run a broker, so someone has to take on assets and obligations.”

Banks have a vested interest in keeping the swaps market opaque, says Das, the former Citigroup banker. As dealers, the banks see a high volume of transactions, giving them an edge over other buyers and sellers.

“Dealers get higher profitability through lack of transparency,” Das says. “Since customers don’t necessarily know where the market is, you can charge them much wider margins.”…

…By the middle of 2007, mortgage defaults in the U.S. began reaching record highs each month. Banks and other companies realized they were holding hundreds of billions in toxic debt. By August 2007, no one would buy CDOs. That newly devised debt market dried up in a matter of months.

In the past year, banks have written off $323 billion from debt, mostly from investments they created.

Now, if corporate defaults increase, as Moody’s predicts, another market recently invented by banks — credit-default swaps — could come unstuck. Arturo Cifuentes, managing director of R.W. Pressprich & Co., a New York firm that trades derivatives, says he expects a rash of counterparty failures resulting in losses and lawsuits…

For now and for some time in the future, CDSs will remain unregulated and their trades will be done in the secrecy of Wall Street’s biggest securities firms. That means counterparty risk will stay out of the sight of the public and regulators.

“In order for us to get away from worries about counterparty risk, in order for us to encourage more trading and more transparency, there’s got to be some way to bring all the price data together with exchange trading or a central clearinghouse,” Backshall says.

Until that happens, the sword of Damocles will remain poised to fall, as banks, hedge funds and insurance companies can only guess whether their trillions of dollars in swaps are covered by anything other than darkness.

To read the entire story, go here. / Bloomberg.com

The Rag Blog