Stop thief!

Stop thief!

How the internet happened

and why it’s in danger now

By William Michael Hanks / The Rag Blog / October 15, 2010

Also see Mike Hanks’ companion article: Net Neutrality / Open Internet Under Fire And see ‘Save the Internet’ video and Net Neutrality resources, Below

Somebody is trying to steal your shiny new bicycle and I know who it is. What you can do about it depends on being able to dissuade their accomplices from participating in the crime.

Your bicycle is the Internet. It takes you to far away places, on adventures, to see friends and family, and it informs your opinions. Right now you can hop on it and go anywhere you want. But if five monopolistic corporations have their way you’ll have to ask their permission first.

A few short years ago there were thousands of local Internet Service Providers (ISP’s). They sold, for a monthly fee, telephone modem access to the Internet. Beep beep, whistle, buzz, long wait. Then cable service providers began to offer the service over much faster cable lines. Cable companies merged and consolidated so that now four or five corporations operate in protected monopolies across the entire country.

The biggest are Comcast, AT&T, Verizon, Time Warner, and Cox. It’s not enough that they have a monopoly in your community, or that you pay them for the use of your Internet highway. They want to control where and how fast you can go and who you can do business with as well.

Why is this a theft? After all it’s their cables. Because, if you have ever paid taxes, the Internet belongs to you. It was conceived with tax dollars spent on your behalf by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Like most bureaucratic projects, it began with a memo:

Dated April 23, 1963, the memo was dictated as its author, Joseph Carl Robnett Licklider, was rushing to catch an airplane. Licklider’s task might have been easier if he had been pursuing a more conventional line of computing research — improvements in database management, say, or fast-turnaround batch-processing systems. He could have just commissioned work from mainstream companies like IBM, who would have been more than happy to participate. But in fact, with his bosses’ approval, Licklider was pushing a radically different vision of computing.

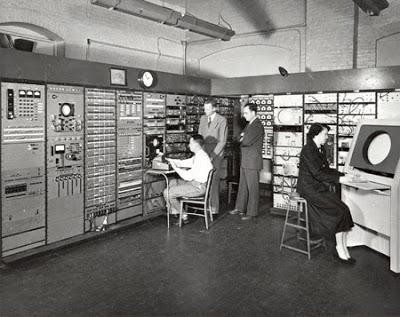

His inspiration had come from Project Lincoln, which had begun back in 1951 when the Air Force commissioned MIT to design a state-of-the art, early-warning network to guard against a Soviet nuclear bomber attack. The idea — radical at the time — was to create a system in which all the radar surveillance, target tracking, and other operations would be coordinated by computers, which in turn would be based on a highly experimental MIT machine known as Whirlwind: the first “real-time” computer capable of responding to events as fast as they occurred.

Licklider, who was then a professor of experimental psychology at MIT, had led a team of young psychologists working on the human factors aspects of the SAGE radar operator’s console. And something about it had obviously stirred his imagination.

By 1957, he was giving talks about a “Truly SAGE System” that would be focused not on national security, but enhancing the power of the mind…. he imagined a nationwide network of “thinking centers,” with responsive, real-time computers that contained vast libraries covering every subject imaginable. And in place of the radar consoles, he imagined a multitude of interactive terminals, each capable of displaying text, equations, pictures, diagrams, or any other form of information.

By 1958, Licklider had begun to talk about this vision as a “symbiosis” of men and machines, each preeminent in its own sphere — rote algorithms for computers, creative heuristics for humans — but together far more powerful than either could be separately.

By 1960, in his classic article “Man-Computer Symbiosis,” he had written down these ideas in detail — in effect, laying out a research agenda for how to make his vision a reality. And now, at ARPA, he was using the Pentagon’s money to implement that agenda.

Licklider’s research program was so successful, in fact, that it’s now hard for us to remember just how visionary it was. IBM and the other major computer manufacturers were going in a completely different direction at the time, emphasizing punch cards and batch-processing machines suited to the needs of the business world. Mainstream computer engineers tended to see the ARPA approach as totally wrong-headed. Use precious computer cycles just to help people think? What a waste of resources!

Thus his memo on April 23, 1963, which he addressed to “the members and affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network” — they would have to take all their time-sharing computers, once the machines became operational, and link them into a national system. “If such a network as I envisage nebulously could be brought into operation,” Licklider wrote, “we would have at least four large computers, perhaps six or eight small computers, and a great assortment of disc files and magnetic tape units — not to mention the remote consoles and Teletype stations — all churning away.”

Leave aside the primitive technology and the laughably small number of machines: The vision that lay behind that sentence is still a pretty good description of the Internet we have today. Indeed, Licklider’s Intergalactic Network memo would soon become the inspiration for the Internet’s direct precursor, the ARPANET.”

— “DARPA and the Internet Revolution,” by Mitch Waldrop

One big problem remained and that was how to get all these computers physically linked to one another. The job of laying wires to each computer even in the U.S., much more so to computers all over the world, was monumental. However, a simple solution was found in using existing AT&T telephone wires.

Essentially the network leased long distance lines and kept them perpetually open as in a never ending long distance call. But static in the system posed another problem. When data was being transmitted, if the stream broke, the data was useless — mere bips and beeps without meaning.

To solve that, a method of correcting errors was developed along the lines of the U.S. Postal Service. The data stream was broken up into packets, each with the address of the sender and recipient. That way if a packet were unreadable it would be resent and added to the coherent data stream. After some hardware and software design accommodations, the inter-network system — the Internet — was a reality. It was a pretty small reality then but it had profound implications. With simple scalability it could be extended anywhere in the world, or, as in Linklider’s original, perhaps tongue in cheek memo, to the Galaxy.

The content was primitive by today’s standards — ones and zeros — computer code. But that soon changed. Standards were developed to translate the bits and bytes into letters and numbers. The first email programs were written. And the whole system met it’s design criteria — no single node was necessary to exchange information. It could just be rerouted. So if those darn commies blew up a computer somewhere in the system — no problems mate. The world went merrily on as if nothing happened.

But the thing that really made the Internet what it is today — the thing we all love and the main reason we use it — was the Graphic User Interface (GUI). That’s why we can send Aunt Martha pictures of the kids, why we can see animation of the space station construction, and why we can read and write blogs like this. The ability to see pictures and hear sounds, to tell a story, to research a term paper, to do all the things and go to all the places our shiny new bicycle will take us — it all depends on the GUI.

The GUI was a gift. We didn’t pay for it like we did the design, architecture, hardware and software that put the Internet in place. It was a gift of a few good geniuses who wanted to do a few good things. Tim Berners-Lee, while at CERN, the European Particle Physics Laboratory, invented a way to transmit images over the Internet — and the World Wide Web was born. He could have patented his invention, protected it with copyrights, and made a bizzillion dollars. But he didn’t. He gave it to us, free of charge — a gift to the people.

So not only is the foundation of the World Wide Web — the Internet — yours because you paid to develop it, but the World Wide Web itself — the Graphic Interface — is yours because it was a gift.

So what’s the problem? The problem is a bunch of fat cats who can barely tie their shoes and could never in a million years create it themselves want to steal it and sell it back to you. Who would have the presumption, the hubris, the unmitigated gall to try such a thing? I’ll give you a clue. It’s who you make your check out to each month for your Internet connection.

It’s the huge corporate vultures who are not content to simply have a monopoly on your Internet business — they want more. They want to leverage their monopoly to sell you services that you would otherwise freely choose on the open market where their limited abilities and lack of innovation make them uncompetitive.

Here’s how it works. Lets say you use Vonage or Skype for phone service. You pay the modest fees, they give you good service, you save money. But the company that you use — that you pay to use — to connect to Vonage — your Internet Service Provider (ISP) — sees that’s a good business and wants to offer it too. So mysteriously your calls with Vonage buzz with static, get dropped, aren’t as clear as they used to be.

Then, here comes your Internet Service Provider to the rescue. They have a service. It costs a little more but it’s more reliable so you switch. But because they have their foot on the hose — your Internet connection — they have just turned down or turned off your connection to Vonage without your knowledge. They think people are stupid enough not to notice.

Well, people do notice. So now they have a problem. They have just hijacked your freedom to choose but how do they get away with it? Enter the accomplices — your representatives. You see, if the law doesn’t forbid this practice — or worse, if it encodes it into law — then there’s nothing you or anybody else can do about it.

They have just stolen your shiny new bicycle and are offering to sell it back to you and it’s all perfectly legal. Well, after all, Representatives and Senators have to fly in jet planes and live high on the hog too. What’s a little graft in the free market. So what if they are selling you out to line their pockets. What are you going to do about it — complain? Take a number.

There’s only one currency that is slightly more valuable to elected officials than dollars and that is votes. And that’s what you have. You may spend every dime every month just to live or send your kids to school but you still have what your representatives want just a little more than money — a vote. Or more exactly lots of votes. So if you exercise your oversight over your representatives and you convince enough other people to do the same, you win. If not, you lose. It’s just that simple.

The theft of Net Neutrality is only one crime that moneyed corporations have tried to legitimize by recruiting your representatives as accomplices. But it’s one of the most important because if they can control your access to services that you choose to purchase on the Web they can also control your access to any kind of information about the world that you live in. They can tell you where you can and cannot ride your shiny new bicycle because now they own it.

Net Neutrality is non-negotiable if you want to go where you want to go, see what you want to see, and continue to create and have access to ideas of your own choosing. Act now. Sign the petitions. Call your Senators and Representatives. Write them, email them. Get your friends together, make signs and march in the streets. Because once your freedom to ride your bike wherever you want to go is gone you may never get it back. Don’t let ’em steal the Internet — it belongs to you and to the generations to come.

[William Michael Hanks lived at the infamous Austin Ghetto and worked with the original Rag gang in the Sixties. He has written, produced, and directed film and television productions for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, The U. S. Information Agency, and for Public Broadcasting. His documentary film The Apollo File won a Gold Medal at the Festival of the Americas. Mike lives in Nacagdoches, Texas.]

Also see:

- William Michael Hanks : Net Neutrality / Open Internet Under Fire / The Rag Blog / October 15, 2010

Net Neutrality Resources:

- Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF): Anyone who watched John Hodgman’s famous Daily Show rant knows what Net Neutrality means as an abstract idea. But what will it mean when it makes the transformation from idealistic principle into real-world regulations? 2010 will be the year we start to find out, as the Federal Communications Commission begins a Net Neutrality rulemaking process.

But how far can the FCC be trusted? Historically, the FCC has sometimes shown more concern for the demands of corporate lobbyists and “public decency” advocates than it has for individual civil liberties. Consider the FCC’s efforts to protect Americans from “dirty words” in FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, or its much-criticized deregulation of the media industry, or its narrowly-thwarted attempt to cripple video innovation with the Broadcast Flag.

With the FCC already promising exceptions from net neutrality for copyright-enforcement, we fear that the FCC’s idea of an “Open Internet” could prove quite different from what many have been hoping for.

- Democracy Now: The internet and telecom giants Verizon and Google have reportedly reached an agreement to impose a tiered system for accessing the internet. The deal would enable Verizon to charge for quicker access to online content over wireless devices, a violation of the concept of net neutrality that calls for equal access to all services. The deal comes amidst closed-door meetings between the Federal Communications Commission and major telecom giants on crafting new regulations.

Net Neutrality Petitions:

- Free Press

- Move On

- Al Franken

- Progressive Change Campaign Committee

- Change.org: List of Citizen Initiated Petitions

Some You Tube Videos:

Thanks for a good review. I can see the vague political outlines of the Internet situation, but it would be good to see an analysis of how the politics is likely to play out — if the corporate giants get their way. I imagine the corporate media would have to do something to anger the average Facebook user, in order to generate and focus the same kind of grassroots political anger we now see with

People have got to realize their civic duty is not fulfilled by taking off an hour from work to vote every two years.

People must inform themselves and know what their representatives are really doing with their power and money.

At least an hour of serious study a day on the issues coming before Congress is the minimum commitment.

Are people ready to accept that

The above posters both raise important points. Voters should be responsible to get the facts. The other raises a specific charge that, based on my visit of the apprisal site, appears valid. This raises the question – if the media conceals 'game chainging' info like that from the public, how does the voter find the truth? This is a troubling situation. Everyone knows some level of bias